Early Middle Ages

The early attempts of democracy

Around 500 BC the Athenians developed the system of democracy. While for many of our political institutions and symbols we use classical names and even classical designed buildings (Athenians would indeed be able see many similarities in several of the government buildings in Washington) the differences between the early democratic systems and the ones in use now are very different.

Greek democracy was limited to the male population of the top layer of the society; they didn’t include women and also not slaves – which together would have made up as much as 75% of the population of the Athenian city state, add the children to this group to it and you end up with only a few per cent of the population actually being active participants in this democracy. Nevertheless some very important democratic elements were established here.

Interestingly also the individual household was seen as one of the layers of the political system with the man of the household having autocratic authority.

In north-western Europe a rather different and arguable more democratic system – be it still at a very primitive level – existed at that same time.

Over the centuries tribal systems here had evolved into a tripartian system and consisted of chiefs, warriors and farmers. During tribal times the organisation of the tribe was rather flat. A tribe consisted of a number of families with a common ancestor. All free male members of the tribe could participate in the assembly (thing/ting/ding/mallus). This group elected their tribal chief/king. The king was advised by the elders of the tribe.

Only from Merovingian times – when the tribes left their nomadic live behind – are we seeing that the top worriers started to form a ‘nobility’ class. Initially the chief might also have had religious (sacral) powers. This tradition might also be the origin of the religious powers of the Carolingian rulers which started to become more profound again under Charlemagne.

We also saw a similar development in Mesopotamia around 3000BC when the first Sumerian city states started to develop, also here it has been argued that the first kings evolved from the city temples. However, as far as we know there was nothing democratic about the systems of the Sumerians and consequent dynasties in the Anatolian-Sumerian-Egyptian region.

The Greek system of institutionalised democracy was truly developed – as a world first – by the Athenians.

In the European Middle Ages however, there was very little democracy. The tripartian system was well and truly alive and inequality remained the natural order. The power was with the nobility and increasingly with the clergy, ensuring that the other 90%+ of the population was kept strictly under control with fear, violence and damnation as their tools.

The end of tribal structures

However, in north-western Europe, it was these Germanic traditions that started to form the basis for our modern democratic societies. The early democratic developments here had more to do with the Germanic Thing than with the Greek and Roman Senate. However, interestingly Roman Law became the legal foundation of continental north-western Europe. This was thanks to the rediscovery of the Codex Justianius from 530, this originated in Constantinople and the surviving manuscript was kept in Pisa since 700. Here it was copied and brought to Bologna.Here the Italian jurist Irnerius of Bologna (ca 1055) studied and taught the Corpus juri and provided it with commentary. A century later, the Bologna jurist Gratianus brought the first collection of dialectical works together of Church law known as Decretum Gratiani. Because of these juridical activities the city became, during the High Middle Ages, the center for legal studies for continental Europe.

The tribal system slowly weakened during Merovingian and Carolingian times. Society started to develop more along social groups. From Charlemagne onward the tribal political structures started to be replaced with the institution of the king, however, the real power (and income) of the king was still manly limited to his own domain. That ‘s why we see Merovingian and Carolingian ‘Empires’ so easily collapsing.

Dark Ages

Since the collapse of the Carolingian Empire most of Europe fell into anarchy. With the invasions of the Vikings in the north, the Magyars in the east and the Moors in Spain and southern Francia, it was every man for himself as there was no central power that could muster an army to fight the invaders. Within Europe there was an enormous land grab between these war lords, with soon nearly every village ruled by a separate Lord. Northern Italy was one of the areas less effected by the uproar, here the Carolingian systems survived and a complex legal structure remained in place with courts and tax collection, this made this region in the 10th century the most prosperous region of Europe. For different reason Norman Italy in the late 11th and 12th century (Southern Italy and Sicily) was also able to establish well functioning feudal court and taxation systems.

After the various Viking invasions stopped and the invaders had either settled or left, there were a lot of unemployed warriors (knights). They now started to concentrate on fighting each other in order to increase their land and power. This led often to outright terrorism across the lands where as usual the ordinary people became the key victims..

The new motte and baily fortifications from these war lords became also the staging posts for further warring against neighbouring war lords and over the next 200 years every territory in north western Europe has their own warlord often at distances of only 5 kms apart.

The war lords also started to dominate the rural region around his castle on the one hand they provided protection to the farmers in the area in an ever more aggressive environment but as a consequence these farmers became more and more dependent on these lords, this grew into the system of serfdom.

It were the strongholds of local vassals which emerged around the year 1000 which started to give the impetuous of many if not most of the villages that are still with us today. These local chiefs started to assemble their own vassals as armed warriors. This resulted in was an enormous large number of small private armies. They consisted of a mixture of court staff, vassals, clerks and farmers (serfs). While in general these private armies were operated under the control of the feudal lord, very often they also operated on their own in the many family feuds and other conflicts that were a continuing part of life in the Middle Ages.

This also gave new impetus to the cavalry, which first stated to emerge under Charles Martel. In order to be successful these horsemen (farmers) needed to become more specialised and this militia increasingly required more money and as a consequence increasingly only the aristocracy could afford to take part in the militia.

Chivalry – the cult of knighthood

In the middle and north European regions this developed during the 12th century into the ‘cult’ of the knighthood complete with its own inaugural ceremonies, codes of honour, hairstyles, fashion and tournaments. Chivalry had its roots in the Roman Empire. Cicero wrote about virtuous citizens where honesty and efficiency came together for the advantage of society.

Many of the original militia turned knights were not necessarily from noble origin, however over time most became part of the lower nobility. In northern Italy these private armies were closely linked to the cities in that region, with more emphasis on the militia than on the ceremony.

Tournaments

While elements of the tournaments have a long history, the medieval tournaments were a unique European development. It can partly be seen as a military training and in particular for the young male nobles this training started already with toys at a very early age. However, another interesting aspect of the tournament is its competitive nature. The event wasn’t without danger and there are several prominent European nobles who died in the competitive mock battles.

With the invention of the bascinet (face shielded helmet) it became important to wear personal marks indicating his identity. This led to the development of heraldry that initially was predominantly used on their weapon shields. The explosion in coat of arms also led to the function of herald. His task was to announce the knights at tournaments and for that he needed to know all those coat of arms by heart. He also became in charge of the organisation of these events and soon became the expert in the history of the knights, their coat of arms and the wars they fought in. On the battlefields they also became the messengers between the warring parties.

In all the amour of the knights consisted of 24 pieces with a combined weight of 27 kilo. They were unable to dress and undress themselves and needed their page or squire to assist them with that. In England, the cost of weaponry and amour for a knight and his horse was around 20 pounds , the equivalent of the income of a manor for one year.

As we saw above the church opposed the infighting that started to occur as well as the traditions of knighthood and the materialistic pomp and ceremony around with it. From the 12th century onward we see that the Church becomes increasingly involved in the the knighthood system. They started to remodel knighthood into a sort of order and in fact several military orders were established around the concept of the crusades.

Other changes that the Church was able to implement included that knight inaugurations (dubbing) from now on were held in a more modest way and in chapels and churches. Chivalry became a Christian value and as such the Church became more and more involved in the organisation of warfare aimed at protecting the Church. The strong influence of the Church on knighthood continued right until the end of this type of warfare a few centuries later.

Chivalry, is also seen in the context of an emerging change in culture and manners an awareness among the nobility of increased civilisation. Most knights were therefor well educated and could read and write, this led to an increasing number of knight writers (trouvères and Minnesänger). Among the knighthood this became a badge of distinction. These trends started at the Court of Aquitaine, where troubadours performed (love) poetry, this rapidly spread to all the courts of Europe, and courtesy became the new way of treatment at the court. But chivalry and any other cultural developments only applied between members of the aristocracy, not between them and the ordinary people. Chivalry during a battle could see that within the conquered party the nobility was saved as they were seen as peers, but the army of peasants, or the citizens in conquered cities, were slaughtered.

As mentioned above, the Church also didn’t shy away of also bending the military system to their own advantage by using these warriors to fight for the church (holy war) and this became a critical element of the many crusades organised by the Church throughout Europe and the Middle East. Those who died in a crusade went straight to heaven. In the context of the infallible medieval belief system this alone brought many knights to the Crusades as many of them were very much aware of the large range of sins they had committed in the eyes of the Church and every single person in the Middle Ages was paranoid about damnation and ending up in hell

It was during this time that the prestige of the knighthood grew to phenomenal heights. Even kings started to present themselves as knights.

With the arrival of the cannon in the 1330’s the castles and their knights started to loose their importance as strongholds and warriors, but the legacy of their 300 years of rule still exists in the 21st century. Many castles were built strong enough to last into modern times and knighthood still exists be it now in a more ceremonial sense. A major castle rebuilding program saw many of these fortresses changed into far more comfortable castles.

Tribal chiefs and early knights became later on known as the ancient nobility. Their nobility was based on landownership based on hereditary Germanic law that kept landownership within the family. Modern (feudal) nobility started to emerge after 1100 when the Emperor started to provide knighthood privileges to its ‘bonded’ or unfree military chiefs and top officials (ministerialis). By 1350 these two groups had largely merged.

Ministerialen – Ministerialis

These were unfree servants of the king, often the lower ranked knights,recruited from the servant families (not from the farmers/serfs). They could not marry or move out of this position without the permission of the king, nor could the transfer property or inherit property. Like the noble knights they in general were well educated and could read and write. They were appointed for managerial (farming) or administrative (court) functions. This system developed towards the end of the Early Middle Ages specifically in East Francia (Germany). After the collapse of the Carolingian Empire this region fell back to the five main tribal kingdoms and the emerging emperors had difficulty recruiting people from the nobility who were not interested to work in servitude for the Emperor. In France and England there was a tighter control around the king and these functions were normally taken by the lower knights. The early sheriffs for example came of the ranks of the barons, only after 1000/1100 became they part of the administrative organisation.

The powerful Conrad II was adamant to create a stronger central control in Germany and started to recruit ministerialis in larger numbers. This situation continued over the next hundred years and also spread to the Low Countries (especially Holland and Utrecht – as we saw in the history in relation to the van Amstels).

The nobility vassals were in effect the standing army of the local Lord. When mobilisation was announced they received a personal call to meet the Lord on horse. The serfs an other farmers could also be called upon and would be put under the command of of a military official of the Lord. In the early Middle Ages the most common military operation was that of the ‘chevauchée’ a rather small group of warriors mainly or only consisting of knights. These personal armies often consisted of hundreds of knights who individual often also shared in the plunder – rather similar to the raids of the Germanic tribal chiefs.

Case study the Flanders Anarchy of 1127/28

The anarchy that followed the murder of Charles the Good Count of Flanders is a good example of the fragile political position of the new order that was starting to develop. On one side are the warring nobles who over the past 200 years had made their living out of fighting each other. As land was the currency of the time, wealth could only be generated by extending their territories and this could only be done through marriage and war.

During this period of transition the knights (milites/soldiers), were among the most feared as their only reason of existence was fighting, either for their Lords, their family, others who would employ them and often they also operated as individual mercenaries and didn’t shy away from killing and looting for themselves.

Galbert of Bruges in his account on the murder of Charles the Good doesn’t rank them on an equal footing with the rest of the nobility, he even referred to some of them as serf-knights (servi). There were many different levels, some were vassals of the count, other vassals of his vassals, others were Lords in their own right, others were part of the households of other knights, some were simply mercenaries and others (younger sons of Lords) were landless and like so many others wanted to try their luck in the big smoke. These knights were only there for the fighting which added a dangerous mix of violence to an already volatile’s situation of a society in transition.

On the other side , driven by enormous economic growth following the Medieval Warmth period, the economic power was shifting from the country to the city. For these cities to prosper peace was required. Both the Church and the Prince (as in the leading king, count, duke) favoured peace and this brought the concept of the Peace of God or Peace of the King/Count (see below). In some of the emerging states – i.e. Flanders – severe punishments existed for the nobility when they broke this peace.

In the middle of all of this – or above all of this – was the ‘Prince’ these shifts in power brought him in conflict with the lower nobility who now saw their avenues cut off from increasing their wealth, while at the same time the wealth and power of the Prince grew exponentially. At the same time the emerging cities continuously demanded more and more privileges for liberties and mercantile freedoms, in order to keep the booming economy going (and pay taxes to the Prince so he could fight his wars against revolting nobles or neighbouring Princes who wanted to extend their territories).

High Middle Ages

Peace of God

A breakthrough that most certainly has been instrumental in the change over from the Early Middle Ages to the High Middle Ages was the system of the ‘Peace of God”.

It was until the Church started its reforms in the mid 10th century that a new central force was able to bring some civilisation back. At that time also the invasions had stopped or had been able to halt. What now had remained was the fighting and the terrorising of roaming knights.

With its renewed self confidence the Church started to counteract this and established the principle of Peace of God, this was aimed at protecting the poor (as in everybody who was not a Lord or a knight), in particular women and children and the local churches and their properties. Publicly sworn oats were required by bishops who organised special councils for this purpose, summoning the local rulers to these events.

They used its own supernatural weapons in all of this, threatening those who broke the peace oath with the wrath of God and the Saints and foreshadowed death and destruction brought upon those who would upset them – and as per the Bible stories as devout Christians they were very aware of the violent nature of these deities if they would not be obeyed. In particular local saints were seen as very powerful in protecting their own church, people and properties. Maximum supernatural power existed if these church had relics of these saints, the more relics the more venerable and powerful these saints were. Plenty of miracles were mentioned by bishops, priest and monks showing the supernatural powers that had been evoked.

Even these impressive warriors were highly effected by this and the threat alone was often enough, to adhere to the directions of the Church, new attitude also lead among other things to the above discussed chivalry.

Once regional power started to increase (see below), the Peace of God was also supported by kings counts and dukes as that allowed for more and better economic developments, especially in the emerging cities. There were severe penalties on breaking the peace. This created severe tension between the rulers and their vassals, as the creation of their wealth depended on wars aimed at extending their territory.

It can be argued that the Peace of Good principle became the start of what we now call public order and that its success has greatly contributed to the prosperity that is linked to the High Middle Ages.

According to Robert Fossier [1. The Axe and the Oath, 2010, p263] the movement started around 990 in central France, reached northern France and Flanders in 1020, Germany around 1050 and Italy towards the end of the century.

While, as we all know, this didn’t stop wars and fighting, in the absence of proper security laws and supporting legal systems, it made an enormous positive contribution to establishing some basic security after the previous couple of dark ages of total anarchy.

With plenty of fighters no unemployed the Church offered them the alternative of the crusades, which indeed many did take up. This also shows an interesting light on the morals of these days. Violence was still very much accepted and promoted by the Church as long as it was directed to non Christians and heretics.

Also the peace didn’t apply to differences between people, here still very much the ‘law of the land’; the ancient customs applied, dating back to tribal times, they mainly concentrated on securing the cohesion of the community and the loyalty towards that community and the people within it. The Church had no power in these cases and also largely stayed out of these affairs. During the High Middle Ages – towards the end of the 12th century – more and more written laws started to appear, specially in the emerging cities, covering elements of those old customs that could be put in fixed rules and regulations, obvious trade also was greatly stimulated by fixed written down laws.

The emergence of regional powers

Slowly during the late 10th and 11th centuries regional powers started to emerge. While basically every war lord had the means to built the rather ‘cheap’ motte and baily fortifications with earthen walls and wooden structures; building stone castles was a different thing all together, this led to a consolidation of (regional) power. Merchant could also take shelter in these more sturdy structures, as a result trade also started to come back and merchants started to built up new wealth. An improvement in climate spurred up more agriculture output and this led to an increase in population. Merchants needed a peaceful environment to flourish and they were instrumental in the formation and growth of cities.

The increase in regional power also saw a renewed and further development of the vassalage system whereby the nobility (as a social group rather than a tribal group) became more tightly brought under the control of other socially organised groups such as regional ecclesiastical and secular powers. Instead of bounty, increasingly these warriors received land and later on privileges and the local tribal chiefs became the dukes and counts of the Middle Ages. Within the feudal Curia – the Latin name for Thing/Mallus – vassals provided advice to their Lord, increasingly supported a a lay administrative organisation.

The counts and dukes assisted by their knights were able in creating a more peaceful environment, at least at a local level, they happily continued their warring activity at a regional level, this obviously created its own problems.

In France, Germany and England we see a more centralised power arriving under king or emperor, in the Low Countries the cities and later the Burgundian dukes were the driving force behind these changes. All these changes derived from the Court systems as they had developed all over Europe. The 11th century saw a rise of a more organised and centralised society, where the secular and ecclesiastic functions were beginning to separate from each other. The Capetian king Philip I (1052-1108) married to Bertha of Holland, was the first French king to lay a solid foundations for royal power by developing administrative systems and by limiting the power of the very power vassals.

Council of the King/Count/Duke

The concept of the tribal Thing and the Curia continued in what would become the Council of the Duke or Count. Within this more formal structure key vassals continued to provide advice to their Lord, with ministerialis (unfree servants) providing the administrative and managerial services. By the 13th century this had become a more or less permanent college that travelled with the Court in order to provide advice where ever the Lord resided. Governance is this period depended still very much on the personal presence of the Lord.

Members of the nobility were ordered to participate in the Court Council to provide advice, some had a more permanent position, others only occasionally participated. When the Court was travelling it was mainly the local nobility who, outside the permanent Council, participated. The position within the nobility also played a role here the larger the landholding that resorted under a Lord the more influential his position in the Court Council.

Over time clerks became also part of this system, who were, unlike the ministerialis, paid for their services. Specialised departments started to develop such as those responsible for financial affairs and legal affairs. This lead to more centralised places from where the governance of the area became centralised, slowly ending the period of travelling courts.

A key development, in the 12th century, is also the introduction of the Exchequer system in England, which became the basis of the financial accounting system of the kingdom. Twice a year sheriffs of all the shires had to deposit their royal revenues at the tresorier (treasury). They were administered on the so called Pipe Rolls.

From the 13th century onwards we do see that the nobility claimed more participation in relation to the governance of the country, especially in relation to the rulers demand for taxes to fight his many wars. We see the arrival of the Charter of Kortenberg in Brabant and the Magna Carta in England that are starting to formalise these arrangements.

A new level of ‘democracy’ starts now entering the medieval society which looks remarkably similar to the Athenian system of democracy; a rather small group of males from the upper level of society (nobles, merchants) become the ruling class. Curia now started to be used for this small group of nobles and this evolved in the state court, as different from the household court.

We are now seeing a change happening from territorial developments based of the feudal rich to a structure of state formation around the king, here the king is not just the largest landowner but also the suzerain. From the 14th century onward we than see this further developed from suzerainty to sovereignty, whereby the king’s power is no longer linked to his domains but that he now full territorial control over all of the territory. At this stage the feudal state has been transformed into a monarchy. In this system the feudal Council will be transformed into a Parliament (French, parlement = discussion)

The real power of these Parliaments was that they needed to be consulted when the king wanted to increase or introduce new taxes. Those were excellent opportunities for the nobility and later also the representative of the cities to obtain or extend privileges. It is interesting to note that it was the need for money that started the process of democratisation.

Rank order nobility

Within the Holy Roman Empire the rank order of the nobility was known as the ‘Heerschild’ it was divided in seven shields:

- Emperor/king

- Church nobility including bishops and abbots

- Dukes and Counts

- Lords

- Schepenen (bailiffs and magistrates of the cities)

- Their vassals

- The function of the 7th group is not well understood they later became the free men within the cities (burghers).

For most of the Middle Ages the Court and the governance of the country were totally intertwined. In the Low Countries, it was only during the Burgundian Court that slowly a separation started to emerge. For more detail information see: Dukes of Burgundy.

Also government and the Church were fully intertwined and the secular court also addressed many religious matters.

As an example of this, after 1070 the Counts of Flanders still appointed the provosts of the St Donations chapter in Bruges as their chancellors. From the 14th century onward secularisation started to set in. By 1500 only 8% of the French courts still were clerics (the word clerk is derived from this).

The new political order

Separation between court administration and household

The Royal Courts slowly started to grow into bureaucratic entities which allowed the monarchs and their counts, dukes and bishops (Germany) to extend their powers to all of the corners of their territories. This greatly improved their ability to enforce tax collection. Under a more stable regime it became easier to institutionalise these powers. Kings started to stop moving around and Courts were established and embellished, administrative and legislative complexes followed suit.

This also undermined the influence of the ancient nobility, while the king still needed them for military support, the governance of the countries became increasingly in the hands of a new professional elite of lawyers and bureaucrats trained at the newly established universities.

The ancient nobility maintained their power to approve and grant taxation. As we saw above this was a very powerful tool and led to the first set of democratic principles laid down in charters in Flanders, Brabant and England. However, towards the end of the Middle Ages their position was further weakened partly because the rise of paid-for military services and a forever quarreling nobility with their internal feuds.

Case study of the declining power of the lower nobility

During the 12th and 13th centuries the political situation started to change whereby the kings, counts and dukes became more powerful at the expense of the many landholders who had been able to increase their power to become the new nobility, during the previous centuries.

Of course the lower nobility didn’t accept this laying down. They tried to fight this and wanted to continue to increase their powers – similar to how the rest of the nobility did this as well – through war and marriage.

An interesting case to illustrate how this worked in practice can be found in Holland. In analysing the political murder on Count Floris V of Holland in 1296, this struggle between the two classes of nobility as well as their internal relationships provides a good overview of this. [2. Floris V, E.H.P Cordfunke, 2011]

Several of the lower nobility had been able to build up significant wealth and power during this period. For example the van Amstel family had been minesterialis under the Bishop of Utrecht and had since become knights. They used the ongoing power struggle between the Bishop of Utrecht and the Count of Holland to increase their own influence. However, Floris V was a powerful Count and wanted to increase his position by limiting that of what officially were his vassals, he even had international ambitions, he was one of many claimants of the title of the King of England.

Through marriage the van Amstels had built powerful relationships with other noble families, notably the van Cuyks, one of the old nobility families with extensive properties along the rivers in the Low Countries. At this time they had reached the summit of their powers, Jan van Cuyk being the highest advisor to the Duke of Brabant and an ambassador of the King of England. Other closely linked families included: van Woerden, van Velsen, van Heusden, van Brederode en van Tellingen.

They were all linked through marriages.

During one of the conflicts between the Count and the nobility, Floris imprisoned Gijbrecht van Amstel and Herman van Woerden for resp. 5 and 8 year. After his release Herman van Woerden was not allowed to marry his daughters without the approval of the Count, a clear indication of the power of the marriage relationships.

Also many of the properties were confiscated in this process.

Obviously these issues left deep scars in the families affected. Add to this the rather sudden change of alliance of Floris V from the King of England to the King of France and what could have remained rather parochial range of events – as there were so many throughout Europe – became one that made the history books to become a case study for these medieval developments.

Though Jan van Cuyk the King of England supported the kidnapping of Floris and Gijsbrecht van Amstel became the key organiser of the action plan.. Apparently the plan was to bring Floris to England however, the way the action was botched put questions around this. During a range of confusing and rather unexplainable events the Count was murdered by Gerard van Velsen, apparently in rage.

The conspirators didn’t gain anything from their action, to the contrary they were either killed or imprisoned , their property was confiscated and in the case of the van Amstels they had to flee to Brabant.

New administrative and management systems

The changes that occur now there were more powerful regional rulers required the need for better management, administration and juridical systems. This started to emerge in France during the 12th and 13th centuries at least partly based on Roman and Canon laws and procedures this included lessons learned from the concept of the ‘Peace of God’.

At least at a conceptual level, most of the systems that were developed in France, were also introduced in the Low Countries when Philip the Bold as Duke of Burgundy became Count of Flanders, when the power of the Dukes increased between the 13th and 15th century the systems spread throughout the rest of the region. However, the interpretation and formalisation differed between the various counties and duchies of the Low Countries, who all used their own interpretations of the Roman, Canon and French/Burgundian examples.

It was in Flanders that we come across one of the first civil servants starting to record civil service history. Galbert of Bruges(see above), worked as a notary for the chapter of his cathedral in his town. The occasion for his writing was the murder of the Count Charles the Good of Flanders in 1127. [3. Beryl Smalley, Historians in the Middle Ages]

An example of the raise of power of the civil service can be seen at the court in France there were 8 master accountants at the beginning of the 14th century, 19 by 1484. In 1286 the chancery had ten notaries this increased to 59 in 1361, 79 in 1418 and 120 by the early 16th century. Around 1200 the king of England had 15 messengers and in 1350 60 of them, they were looking after the weekly mail between the court and the county sheriffs.

All these developments started from the functions and activities of the royal court, only slowly a separation between the court of the royal/ducal household and the civil functions started to emerge. It was this period in history where many of the modern institutions were born.

During the 14th century most institutions that would govern Europe well into modern times were established. We also now start to see the formation of a new group of nobility. Many of them evolved around the Court (Court Nobility). Increasingly they received charters that indicated their nobility. They remained distinctively different from the ancient nobility (allodial nobility).

Legal systems

These new developments also required much better laws and consistent regulations. There was far too much authority invested in the ruler. While legal reforms started to occur in the 11th century, the old tribal law system was very hard to stamp out. This was based on local powers. The local tribe/community or its local Lord could judge and punish on the spot, without any due legal process. During periods of anarchy or uprising these old forms of tribal law were applied and this led to very high levels of insecurity. Most people for that reason didn’t travel. Strong regional security from the ruler was needed in order to allow for trade and thus economic growth.

In general term the laws, written by the strongest, also always favoured the strongest. They did little or nothing to improve the overall lot of the poor people.

During the 13th and 14th centuries cities became more prominent and the power of the ruler became regulated in charters and city privileges. Separately these cities started to establish their own juridical systems that allowed them to check and challenge judgments of the ruler, but also to address the all prevalent curse of corruption and favouritism.

In the Late Middle Ages, the prosecutor started to arrive on the legal scene, initially in church courts but soon after legal wizards representing the ruler in legal affairs. Like most of the administrative functions and concepts also this one originated in France.

Other parties also started to use legal representatives in court cases.

By the end of the 14th century the function of royal prosecutor started to grew into one responsible for the public order. He could prosecute people in Parliament, who disturbed the order, damaged any goods belonging to the state or incompetent bureaucrats. Slowly the link between the ruler and the prosecutor became loser in favour of the broader public good.

The function of prosecutor was also added to the regional councils, as the ones mentioned above.

Soon the prosecutor received the assistance of the assistant prosecutor or the attorney-general. The latter being the jurist while the former was in charge of the prosecution.

During the 15th century these functions became separate departments with the regional council structures.

Obviously rather rapidly a large bureaucracy started to emerge around these functions as court cases needed to be documented and kept for future reference. This created the Office of the Court Clerk (Griffie) they looked after the fief registers , administrative document and all of the juridical documentation. Later also criminal protocols and processes were added to the function of the griffie.

These developments were critical for the development of the modern institutions that followed as from here on rules, regulations and protocols started to create transparent processes, more uniform decrees followed both for the regional councils as well as for the highest institutions of the country.

Competing interests between cities and courts

Another problem in these emerging cities was that there was no homogeneous population. There were peasants and the already above mentioned knights. Others that started to become part of the new order were travelling merchants (very few had settled at that stage) and people involved in the courts of the count, abbots and bishops.

So the ruler also faced a complex range of often competing issues that were brought forward to him by the various groups. In order to bring some unity in these situations the members of these fractions and groups heavily relied on oat swearing between members. This became another common feature in this new order. Obvious changing alliances became the order of the day, especially when powers changed or when money started to change hands. Interestingly, social class, what was so distinct during the Middle Ages, often didn’t play a role if it served self-interest.

What becomes clear in the example from Flanders is that there is an increase in the concept of solidarity and community. This increase in self consciousness of the cities also led to spokesmen of the various groups who started to express and articulate their specific needs and requirements, the emergence of political parties.

However, it never evolved to such levels during the Middle Ages. Throughout the Middle Ages this lack of unity would haunt the cities, if it came to the crunch all these groups selfishly went for their own interests. This eventually led to a loss of their privileges and freedoms as the ruler was able – especially once his bureaucracy started to grow towards the end of this period to bring the cities firmly under his (national) control. This early form of proto-democracy was replaced with the autocratic developments that followed this period. The ruler’s representatives were the first line of attack in this battle between the ruler on one side and – be it separate from each other – the nobles and cities on the other side.

The court’s representatives

Traditionally the duke or count had all of the powers to rule. However, he couldn’t be all the time everywhere and at the same time he needed the assistance of the lower nobility to stay in charge of his realm. So in exchange for his services he appointed a bailiff (reeve, schout, baljuw, drost).

During the 13th and 14th centuries cities became more prominent and the power of the ruler became regulated in charters and city privileges. Separately these cities started to establish their own juridical systems that allowed them to check and challenge judgments of the ruler, but also to address the all prevalent curse of corruption and favouritism. The early cities that started to form in the 11th century often did so without direct influence of the ruler, however, rather soon at least a bailiff or schout was accepted by the city as the representative of the ruler. Throughout the Middle Ages however this remained a dynamic situation and only under Charles V was the power of the cities broken in favour of the now super regional ruler.

The rank bailiff was first used – from the 13th century onwards – in Flanders, Holland, Henegouwen, Zeeland and in North of France. The bailiff was one of the first judicial civil servant appointed and paid for by the ruler to represent him mainly in regional areas and regional towns.

In Flanders the count usually appointed the bailiff and in France it was the King. The position originates from France when King Philip II Augustus installed the first bailiff. In the northern parts of continental Europe this position was known as “Baljuw” a direct derivative from the French word “Bailli” but other names are: “drost”, “drossaard” (Brabant), “amman” (Brussels), “meier” (Leuven, Asse), “schout” (Antwerp, ‘s-Hertogenbosch, Oss, Turnhout), “amtmann” and “ammann” (Germany, Switzerland, Austria).

The bailiff had three main juridical functions:

- Prosecutor

- President of the court

- Executor of the sentence

However, the rulers realised that handing these functions over to the nobility could lead to hereditary positions and the formation of fiefdoms that would undermine the power of the ruler and soon bailiff became an appointed and salaried bureaucrat, they were however, still recruited from the lower nobility, being basically (apart from the clergy) the only group was some form of education.

Soon however, the original concept behind the bailiff started to deteriorate as the regional rulers throughout north western Europe needed vast amounts of money for their wars and their courts. In order to generate extra money the ruler started to allow subletting of the function, Charles the Reckless went one step further and ordered that all bailiwicks (baljuwschappen) should be auctioned off and the office given to the highest bidder. During the Burgundian period there were no less than 180 bailiwicks in the Low Countries.

This meant that the office had little to do with jurisdiction but simply became a vehicle to generate money. Throughout the history of this function well into modern times this situation continued in some places worse than in others a good example is given in relation to the bailiff (drost) in Ootmarsum in the chapter: Justice is all about making money.

In the Low Countries the bailiff function could differ. In the cities there was the schout as the representative of the lord while used in the rural areas the the bailiff (drost/baljuw) took that position. There was sometimes also a hierarchical difference, the schout in charge of low justice, while the bailiff (hoog schout) was in charge of high (criminal) justice. But these situations varied from state to state.

The bailiff/schout aloes presided the city’s council of magistrates (schepenbank). Increasingly his position here – often with direct interference of the ruler – was also to select the magistrates or at least influence the elections. A similar level of corruption also often applied in these procedures.

Dyke-reeves

A special mentioning here should get the early democratic system that developed around land reclamation and the accompanying water management systems that had to be developed, this often involved different counties which in the Middle Ages often meant different political powers. However, it were the local farmers and the local communities that formed the management of these jurisdictions. See also: Villages and Serfdom.

Council of the Estates (Staten)

At the same time we do see the emergence of the new merchant elite in the rapidly growing cities in northern Italy and in Flanders. Slowly but surely we now also see trades people and guilds becoming involved in these early medieval system of city democracies, in particular in Flanders, Brabant and the Rhine region. By the end of the 13th century, the ruling nobility could not simply any more implement their will without the agreement of his subjects.

We do see interesting political tension occur during the period of transition. On one side, the ruler find himself increasingly in conflict with jealous nobles, while on the other hand he has to deal with a rapidly increasing individuals and groupings within the emerging cities.

They did no longer want to pay for all the private wars the various nobilities did want to undertake, without a vote in these affairs. As an example after the disastrous defeat of Duke Reinoud I of Gelre in the Battle of Woeringen in 1288 he had run up such high personal debts that he had to mortgage his county to his father in law the count of Flanders. This had also enormous effects on the cities in Gelre who had to cough up most of the money to repay the debts of the count.

The more enlightened rulers adapted to these new developments (Flanders, Brabant, Holland, Normandy), others were reluctant and developments were delayed (France, England) other rulers again resisted (Germany and Italy) and the cities and city states by default started to take control over their own affairs.

In the more liberal emerging states, we see that the three estates (nobility, clergy and increasingly the burghers, represented by the cities) were frequently called together as the Estates (Staten, Parliament) during (annual) assemblies (Landtag, Diet, States General). In the Low Countries we see the arrival of the Staten van Brabant, Staten van Vlaanderen, Staten van Henegouwen, Staten van Holland and the Statenvan Zeeland. (Staten=Estates))

Initially they operated next to or in opposition of the (regional) Court Councils, which in the Low Countries started to become known as the Ridderschap (college of the knights – 2nd estate). The measurement of wealth became money rather than land and this led to the end of the feudal (land based) system, a financial reward system also created a more independent position of both the king and the individual members of the nobility.

Later on we see that the nobility joined the States and started to take an independent position within these councils. This shows that the interests of these two estates became more and more aligned against their ruler, whose court became more and professional with bureaucrats specialised in its various functions.

The first estate, the clergy, hardly ever played a key role in political affairs.

The Council of Brabant were established in the Charter of Kortenberg (1312). The Council of Flanders started to operate after 1330 and from 1384 onwards they were firmly established as the legislative body. Holland replaced its Council of the Count (Ridderschap) by the more representative Estates after the Kiss of Delft in 1428. However, it was not until 1463-1464 that the cities of Holland officially called the first meeting of the Estates. Their trading interests stood often directly opposite of the waring interests of the nobility. It would be very difficult for the Emperor, Count or Duke to make decisions without consulting the Estates. From these times onwards the Ridderschap is totally separated from the Council. While Holland started rather late in this process, they would soon take the lead in the democratisation process of the Low Countries.

In several Counties and Duchies in the Low Countries – after the transition period – the nobility remained unified in the Ridderschap. This institution was further formalised under the Republic of the Seven United Provinces. They represented the nobility in the Estates. The Estates were chaired by the Stadtholder or the Ruwaard, the highest representative of the Count of Duke.

With the increased centralisation of power – from the High Middle Ages onwards – the tension between the king and the nobility increased as the kings became so powerful that they started to undermine the privileges of the Estates. Increasingly the councils from the various Dukes and Counts were centralised under the kings or in this part of the world the Dukes of Burgundy (States General). The Reichstag was the general assembly of the Holy Roman Empire. The first States General of the Low Countries took place in Bugge in 1464, from here the moved to Brussels and after the Dutch Revolt to Den Haag.

The States also played a key role in the situation of succession issues. If there was a son taking over from his father the States simply confirmed the change over and the new ruler confirmed the charters and privileges of the estates. However, if there was no natural male successor the States became far more involved. Remarkably, officially there was nothing set in law that for example would see a smooth transition in the case of a daughter who would take over from her father. Also in the case of under age successions and therefor the need of regents, the States could exert their influence as well as in the case of mental illness or other situations where the ruler became incapable of running the country.

Another area closely watched by the Sates was the alloy used in the coins. When the rulers needed money it was tempting to use less gold and silvers in the coins. However, this would lead to economic and social instability. This specific issue became a key reason for the formation of the States.

While the original charters were aimed at limiting the power of the ruler – and also in consequent arrangements that issue was often mentioned – in general terms the States worked closely together with the ruler. Together they only accounted for a few percent of the total population – who had very little rights. The ‘common enemy’ of the elite were often the common people, half of them living below the poverty line and therefor they had very little to lose, so uprisings were a regular affair in the cities. This required solidarity between the ruling classes and brought the ruler and the Sates more than often together rather than in conflict with each other, this was even the case in the most rebellions state: Flanders.

During popular uprisings we also see other layers of the population participating, e.g. the Battle of the Gulden Spurs (Gulden Sporen Slag). However, none of the popular uprisings were able to establish a lasting democratic movement. There was little or no coordination and cooperation between these groups and as such they were rather easily suppressed by the ruling kings. The Reformation in the end did become a successful popular uprising and at least in some regions (Netherlands) led to very significant political changes, but nothing close to what we now call a democracy.

In the 15th and 16th centuries the smaller cities were also well represented in the democratic systems of the day. However, after the power struggles and internal wars following the death of Charles the Bald, the cities started to dominate these structures and in the following decennia they were basically subdued and lost their independent votes. The region around Brugge (Brugse Vrije) was the last regional structure that was able to hang on to its powers.

Brabant was divided in four quarters, however there was a tack of centralised governance and in particular the Bailiwick (Meierij) of Den Bosch and the Markgrave Antwerp were more or less autonomous, the Maasland Quarter (with Oss) was part of the Bailiwick.

These early medieval systems of democracy started to crumble under the Hapsburg rulers. Brugge lost its prominence after, in 1489, the revolts against Maximilian of Australia were violently suppressed. But in particular under Charles V the end game for the cities was played out. He brutally suppressed democratic movements in Ghent (1540). Independent territories such as Gelre, Cleve, Utrecht and Friesland were all forcefully incorporated in the Spanish-Hapsburg Empire.

The English Civil War, which ended in 1649, marks the start of the system of a Constitutional Monarch, but in fact the power still very much stayed at the top layer. The French Revolution was another attempt to create a more democratic system. 1848 – the year in which my great grandfather was born – marked another milestone especially in north-western Europe with popular uprisings and more demands for democratic principles and slowly but steadily over the next 50 years democracy started to emerge as we know it today.

Most democratic countries still have Parliamentary systems based on the governance structures as they were developed and shaped over the centuries since the Middle Ages. The Estates are now the Parliaments and the Kings Councils are now what in most countries is called the Senate.

Originally as indicated above the rulers were personally in charge of justice. Once the bailiffs were in place the court of the ruler functions as a court of appeal. This also allowed the ruler to keep control over their bailiffs.

Around the middle of the 15th century this function was in the Burgundian countries taken over by the State Councils. They all had their own form of jurisdiction and there was little uniformity between them, which made the appeal process often complex and wieldy. Even within the states there were differences between the various manors that formed part of that state.

In Brabant the hoog schout of the larger cities functioned as the courts of appeal for the local courts.

Centralisation

While the various regional courts all followed their own trajectories, it was the Burgundian influence that led to unification and centralisation of all of the above mentioned functions.

In 1473 Charles the Bold established the Grote Raad van Mechelen (Great Council of Mechelen), the highest court in Burgundy (Supreme Court). After the Dutch Revolt the Hoge Raad (Supreme Court) of Holland was established in 1582, this became the highest court of the emerging Dutch Republic and was modelled on the Grote Raad of Mechelen.

Centralisation was also used to limit the power of the cities and bring them more directly under the control of the ‘state’. This reached its peak under the Hapsburg Emperors Charles V in the first half of the 16th century. Only the northern Low Countries escaped this and here we see the beginnings of the Golden Age of in particular the cities in Holland.

State finances

Throughout history – since the urban revolution, which started in the Middle East – we have seen political cycles linked to wealth creation by the ruling class, followed by debt problems in times of war and famine. This most often led to popular uprisings or external war which led to the overthrow of the ancient regime, the debts were wiped out and a new political cycle started.

In the Middle Ages,wealth was created by rulers through the income from their domains, based on the system of feudalism. This income was mainly used for their (often extravagant) travelling court life and for warfare. However, the courts often did run out of money and in both England and France we see the kings becoming in conflict with church by demanding money from them through taxes, this situation continued for several centuries. Often as much as 25% of the wealth was in the hands of the church and they were exempt from any state taxes.

Domain income

| Agriculture (tenure and tithes)

Water and forest (fishing, hunting, forestry) Swamps and polders (salt mining, water rights) Justice (fines, confiscation) Income from fiefs and property transactions Trade (Toll and duties) Coinage Industry and mining Excise ‘Normal ‘petitions from the cities (beden) apart from special petitions as war levies |

The money economy remained rather small and for the ordinary people ‘debt’ often meant slavery or serfdom. This situation slowly started to change after the Great Death in the 14th century, when serfdom had to be loosened. Rulers increasingly had to start borrowing money to maintain their lifestyle and their wars; apart from that taxes were used to pay for it.

In the late 13th century (France, Flanders) and during the 14th century elsewhere a separation started to occur between the royal court and the management of its finances. For that purpose a Receiver General was appointed, slowly this would evolve in what are now the Departments of Finance. Until that time the ruler himself or his chancellor was in charge of the collection of these incomes through the feudal arrangements.

The Receiver General was in charge of:

- The stewards (rentmeester) who looked after the finances generated by the domains (by 1400 this has stabilised to around 190 stewards in the Burgundian lands)

- The baillifs (baljuws) in charge of legal affairs and the income of jurisdiction, fines and confiscations (by 1450 there were around 180 bailiwicks in the Burgundian lands)

- Specialised receivers of other forms of income that needed to be collected

- Receiver of the beden (petitions) in both the cities and the rural areas (tresoriers).

During the 15th century wars increased and warfare had become more expensive as the nature of it as well as the weapons changed. According to custom rulers were supposed to finance their household and income through their domain incomes and only in exceptional circumstances ‘gewone’bedes’ (taxes) were agreed upon (often in exchange for privileges).

In 1394-1395 the income of the Burgundian rulers consisted for three quarters on their domains. By the mid 15th century they still accounted for two thirds of their income. However, income from the domains was no longer enough and there was an increased request from the rulers for more (permanent) taxes.In the case of Burgundy, taxes started to become a far more important part of their income towards the end of the 15th century, when the costs of warfare started to increase. [4. De Hertog en zijn Staten, Robert Stein, 2014, p193]

This became a problem as citizens (cities and states were not prepared to see the special beden being changed into permanent ones and on top of that significant increases as well. However, under an increasingly more unified Burgundy, resistance was increasingly suppressed. From now on tax was a given with perhaps some discussion on the height of the taxes. The ruler used age old feudal traditions as precedents for the taxes, they included taxation for events such as royal weddings, knighthood ceremonies of royal sons, ransoms for war prisoners (members of the royal court), special representations to the king/emperor (hofvaart), crusades, war effort, purchase of new territories, maintenance of fortifications.

Duchess Johanna van Brabant was advised by Thomas Aquino that the ruler was only allowed to raise taxes if they were used for the common good and in relation to war such taxes were only allowed to defend the country. The ruler also had to make sure that ‘good works’ had to balance the tax burden in order to balance the well being of her subjects.

In the 2nd half of the 15th century taxes stated to become the major part of the income of the state. Similar changes in income had already started to occur in France, where at that time income from the domains was not more than just under 3%, the rest were taxes. In the Holy Roman Empire (which included most of the states in the Low Countries) the (federal) tax situation was significant less as the Emperor had less direct control over the more than 300 princes throughout the realm. However, within these princedoms similar taxes were collected however, they varied very considerable from one state to the other.

While the clergy were in general exempt from taxes, they regularly participated on a ‘voluntary’ basis, especially as the reason for the tax was also to the benefit of the Church and with the state and church so intertwined that could also include taxes for war, fortifications, etc. However, they remained very small in the context of total state finances. A more serious attempt to make the clergy a permanent part of tax collection Charles the Reckless in 1474 issued a ruling that monasteries and other church institution had to pay a 5% tax on the annual income of all properties they had purchased in the preceding sixty years. This led to serious protests and legal challenges but eventually the tax was accepted.

Charles also imposed taxes on his vassals, this was totally unheard off but he used the age old feudal right to request military services from his vassals, by now many vassals had their own vassals and if they didn’t want to provide the military service or only part of it, Charles taxed them all with the so called 6th penny.

The main income of the cities came from excise taxes on beer and wine, sometimes land tax was collected in particular in the rural areas.

While many of the above mentioned administrative, judiciary and financial changes are recognisable in a modern state, the situation in the 15th and even the 16th century remained largely feudal. Nevertheless major efforts in the transformation were initiated in the 14th and 15th century and they were essential steps that Europe took in the modernisation process. In relation to the Burgundian lands the reforms in the financial sector were perhaps the most successful, also the most critical as most of the individual counties and duchies faced bankruptcy.

Until the 17th century all state borrowings were still basically private borrowings by the rulers and that meant that there was a huge risk involved as the debt was wiped out when a ruler died. But also a ruler could change the game at will and get rid of his debts in that way. This for example was one of the key reasons why Jews (key moneylenders) where so often expelled and prosecuted.

In all reality what got established – more or less unwritten – was that the domain incomes became the income (salary) of the ruler. They are hardly mentioned in the minutes and documents of the meeting of the Estates. [5. De Hertog en zijn Staten, Robert Stein, 2014, p193]

The Dutch were the first in the early 17th century to change that system whereby the Estates General (Parliament) became the borrower. In this way taxpayers became involved in government and the debt was no longer wiped out at the death of the ruler. Of course there was now far less risk involved in lending money and this led to a large capital inflow into the Low Countries, which led to the Golden Age of the Dutch Republic. Britain was the second country to follow this system after the revolution of 1688. Changes in other parts of Europe – with more despotic forces in charge – didn’t happen until the 18th or even the 19th century.

The downside of this was that it became much more difficult to cancel debts in case of famine, war. This also especially in the 21st century led to an increase of the political power of the financial institutions and as such their enormous influence in the financial affairs of the governments.

State and Church remain intertwined

This more stabilised environment also allowed the Church to increase its influence on the society; already since Emperors Constantine and Justinius (Codex Justianius), Christian values had become State values, enforcement of them became thus far more easier. Charlemagne picked this up again and followed the same principle. The 6th century historian Tribonian famously wrote: “The will of the Prince has the force of law“.

This enforcement was mainly executed on a national basis, eventually through inquisitions.. On that level the authority of the Church remained important and also provided a level of intellect and organisation that was used by the earlier warring lords to try and establish their power base and to provide a range of administrative and legislative services. This very much assisted the monarchies to develop more modern forms of government.

It was in the interest of both the King and the Church to create an emotional and spiritual authority around this. This was a direct extension of the situation as did exist in the later period of the Roman Empire, which was carried on by the East Roman Empire and also well understood by Charlemagne. The Imperial Insignia played a key role in this as well as the rich cultural traditions that were also institutionalised around King and Church.

The sacral elements provided credibility and authority that made it very difficult for others to attack, as an attack on this institution would be an attack on God.

However, increasingly we also see the flawed fundamentals of this rather unholy alliance as increasingly conflicts arose between the secular and ecclesiastical powers. While the influence of the Pope had increased after the Investiture Controversy, towards 1500 their authority was clearly in decline. Of course what hadn’t helped the image of Church during that period was the fact that there were regular rival popes, many had mistresses and children and a very large number of them were mainly interested in the wealth and the power that the office brought with it and made sure that their family members and associates were enriched by it, rather than that they were concerned in what was good for the Church, let alone that they were seriously concerned about their flocks out there in the various countries. Especially on an international level the influence of the pope was waning.

Equally, increased opposition also challenged the secular powers of the local bishops, who of course with the examples in Rome and Avignon often also misused their powers and moral authority. Furthermore the taxes the Church charged led to an increasing number of peasant revolts, especially in the German countries. This reached a climax with the Ninety Nine Theses of Martin Luther.

Ongoing warfare

While most of the small scale warfare between the various warlords started to decline, the new regional and later on the even larger powers that emerged out of the above mentioned new political and administrative structures created a whole new level of warfare. There was still a mix of the old feudal knightly conflicts involving a local town or fortress, than there were the wars involving the Hanse (see below) or the English and Scottish rulers, which resulted in smaller regional conflicts especially along the north western coast lines.

However, increasingly it were the kings and emperors who started to dictate warfare and under their absolute reign they wanted the local nobility, towns and rulers to contribute to war to defend their boarder, fight the Turks, assist the Pope. Key areas of conflicts were the boarders between the Holy Roman Empire and France along the Flemish and Brabant counties. The boarders between Spain and France and the conflicts between the Emperor and France in Italy. Gelre was an ongoing problem threatening the peace in the Low Countries and brought untold misery to the Brabant town of Oss one of the most effected town in this conflict (see Gelre Wars).

There was most of the time a great reluctance from the local nobility, States and cities to pay their contribution for these wars, they wanted peace not was as it greatly effected their economic prosperity. This caused many conflicts to drag on for decades with many stop and start wars depending on the available money at the time.

Strategic military warfare was largely non-existing. There was the occasional great general, initially still leading rather small raiding parties, but increasingly these military elite on horseback were complimented with large, ill equipped, underpaid and underfed soldiers (landsknechts). There were some more specialised and better trained ‘professional’ armies mainly made out of German and Swiss landskechts. The Swiss in particularly were sought after (expensive) mercenaries, they had become a brand in the Middle Ages, something that it still visible in the Swiss Guard of the Vatican. Interestingly these armies were employed by both sides of the conflicts and based on where the money came from these troops could one day fight the enemy and the next day they were the enemy.

The (fighting or financial supporting) nobility became more powerful during this period as in exchange for their services privileges were handed out to them. This gave them more and more power within their own ‘State’. A good example here are the Dutch nobility who played key roles under the reign of Charles V to only claim their own independence a decade after Charles died.

By the 17th century the situation had deteriorated to such an extend that 30% of the German population was killed during the 30 year war (1618 – 1648).

Case study: The Burgundian Court

The Burgundian Court has its tradition in chivalry, whereby the nobility was expected to rule its realm in a benign way. While cities gained more and more independence the political and judicial powers remained in the hands of the nobility. The Court remained still largely based on the travelling court system which dated back to Carolingian times and even before. This only stared to change early in the 16th century.

Rulers of large regions such as the Carolingian Empire and the Burgundian Duchy had many castles and palaces but in order to effectively reign over their subjects they had to show their presence and the court therefore travelled with them. this – from the very early day onwards – included the treasury.

The Court ruled over some 3 million people spread out over approx 100,000 km2, so a lot of traveling was involved

Time tables travelling court:

- Distances covered by the full travelling court varied from 15-30 km per day.

- On horseback they could cover 30-50 kms per day

- By ship (river) 100 – 150 km per day were achievable.

- Sea travel was the fastest and, with good winds, more than 200km per day could be covered.

Traveling Court during the reign of Philip the Good

| Place | % |

| Brussels | 22 |

| Rijsel/Lille | 11 |

| Bruges | 10 |

| Dijon | 6 |

| Ghent | 4 |

| Mechelen | 0.5 |

| Others | 46.5 |

Source: De Hertog en zijn Staten, Robert Stein

Their function and functioning was similar to most of the other courts in north-western Europe, who all took their lead from their ancient Frankish traditions. The organisation of the court system and its functions was based on the advanced administrative and financial systems of the French Court, from which the Burgundian Court evolved.

Apart from the members of the household the court included the chancellery, privacy council, court of audit. In total these functions included 45 people. A proper separation between the household and the administrative function didn’t occur until well into the 16th century.

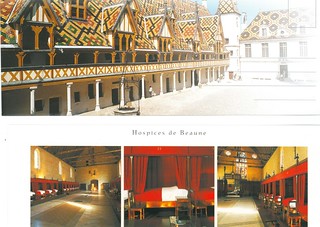

After the Duke the Chancellor was the most influential person of the Court. In Beaune we visited the famous Hospital, which was established by the Burgundian Chancellor Nicolas Rolin, he most possibly was the most powerful chancellor of the Burgundian period, he had near authoritarian powers and became one of the richest persons of his time. It didn’t came as a surprise that during the palace coup of 1457, he was pushed aside.

Locally the dukes were represented by stadtholders and their staff, they also appointed sheriffs and bailiffs, however, the dukes were often also personally involved in these appointments.

French remained the language of the court long after the Burgundian Dukes were gone and extended to the neighbouring Courts of Kleve, Baden, Palatine and even at the Hapsburg Court French was spoken.

The majority of the court staff and the courtiers came from Burgundy, with a minority from the French speaking parts of the Southern Netherlands. After the integration of Flanders 30 courtiers were included in the Burgundian Court, after the integration of Brabant only members of the high nobility were invited to join the Court. The Court was certainly not representative of the various states that formed the Burgundian States, this only started to change under Maximilian of Austria in 1477.

It was not until the mid 15th century that the Administrative Court slowly started to be split of from the Royal Court, until that time the travelling court also included all of the important administrative officers. An extensive study of the court system was made by Jacqueline Kerkhof and is published in her book “ Maria van Hongarije en haar hof (1505 – 1558)’. Each member of the royal family had their own fully functioning court. The key functions included:

- Marshal (highest official)

- Grand Chamberlain (household)

- Seneshal (domestic affairs)

- Cup-bearer (food and drinks)

- Grand Almoner (Chapel)

Many of the senior court function were hereditary and were often more ceremonial and had the title Lord in front of them, while the real functions were executed with the official who had the name Court in front of their functional name. The main sections of the Court were:

- Chapel (religious and music)

- Chamber this was split around 1250 in:

- Chamber (honorary staff)

- Quarter service/inn

Since the 13th century the main sub sections for daily life activities included:

- Bread chamber

- Drinks chamber

- Kitchen

- Fruit chamber

- Stable service

- Quarter services

The personal court consisted between 100 and 200 staff and officials. However, it is estimated that Maria’s court in the Netherlands might have had as many as 300 members. There were rules and regulations for literally every aspect of court life from how hold to hold a napkin, how to cut a bread, how to dress, feed and when and how what to heat and what to light, some of these traditions amazingly continued to well into modern times. In the 15th century the annual costs of a personal court, excluding food and drinks, was around 10-15.000 Rhine guilders. (around €$1 million in modern value). In this case that is based on the combined court of Anna of Hungary and Maria of Austria.

In comparison Anna’s personal income at that time was estimated at 40,000 Rhine guilders (€3 million). The Burgundian court has a rich history in the proportion of the arts. All forms were represented at the court. Paintings, goblins, sculptures, glasswork, jewellery, music and perhaps also science should be mentioned here.

Many of the members of the court actively participated in cultural activities. One of the most famous artists from this part of the world was Albrecht Dürer. Margareta of Austria as well as her father Maximilian were great admirers of him. There are reports of Margareta showing him around at her palace in Mechelen. It was also the tradition that artist would visit the royal family during the Reichstag. Painters such as Jan Cornelisz, Jokob Seisenegger and Titian as well as sculpurer Leone Leoni visited Charles in Augsburg.

The Burgundian court chapel was the intellectual centre of the Court but also produced the best music in Europe according the European contemporise and the most famous musicians came from Flanders. Polyphony developed here for the first time; composed harmonies. Famous composers from the Burgundian and Hapsburg courts include: Johannes Ockeghem. Josquin des Prez, Pierre de la Rue, Jacobus Clemens and Nicolaas Gombert. It wasn’t until the reign of Emperor Ferdinand I that the chapel became formally organised under a director of music (Kapellmeister).

One of the most well known aspects of the Burgundian Court were its extravaganza festivals and celebrations, they were steeped in the tradition of chivalry with tournaments as one of the central elements off any festivity; the dukes were active participants and several were injured and some even died at these activities. Banquets was another highlight which reputation was famous throughout Europe. The Dukes themselves often headed the organisation of the events as the president of the feast.

Also part of of the ‘theatre state’ were the funerals. These were in particular important to very clearly proclaim the next ruler and his relationship with the deceased. The funeral of Philip the Good in 1467 became the blue print for the funerals of his Burgundian, Hapsburg and Dutch successors. There were no less than 1200 participants in the Philip’s funeral procession in Brugge. His corpse was transported under a canopy of gold cloth from the Prinsen Hof to the St Donatius church, behind the coffin followed his First Equerry with the Duke’s sword held in the air. He was followed by 20 nobles in black robes. The new Duke Charles followed with two bastard son and two bastard grandsons, plus all of his own personal attendants and officers. The church was lit by 1400 candles, the service lasted 4 hours and the following night an armed guard of honour remained in place. More masses followed the next day before the internment took place. After this – in front of all to see – Philip’s First Equerry handed over the sword the Charles’ First Equerry. After this Charles’ followed his First Equerry, who also held the sword high the air, outside the church.

After the cenotaph was finished in Champmol (Dyon) another procession tool place six year later through Flanders, Brabant and Luxembourg and Lotharingia, again with the sword playing a key role. His body was transferred however, his heart and intestines stayed in Brugge. A prominent attribute was added to this event, a richly decorated duke’s hat. In following funerals public announcement of the death of the ruler and proclamation of the new ruler were shouted (cris) during the ceremonies.

The deaths of family members was also followed by full pomp and ceremony funerals. If those family members dies elsewhere funeral processions were often also staged in places such as Brussels, Brugge Ghent. Mechelen and later The Hague and Delft.