The Investiture Controversy

Introduction

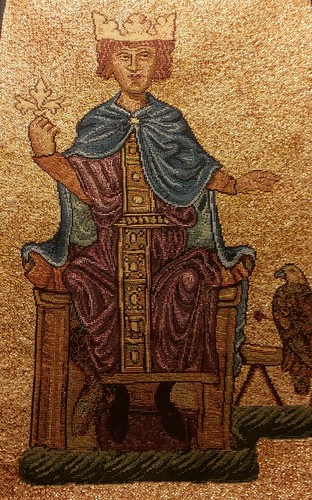

A key element of controversy between state and church, that started in all earnest several centuries later, dates back to the Roman Empire. Ever since Emperor Constantine created a tradition of veneration around his personage the position of king and emperor were seen as being separate from the more secular system of the lower nobility. Kings and emperors were Gods rulers on earth, kingship was made a sacrament and emperors were crowned by popes. They therefore enjoyed shear unlimited powers. However, during the reign of Emperor Justinian, in the 2nd half of the 6th century, ‘God’ did become more worshiped and emperors less.

After the fall of Rome the pope lost his influence, outside the Papal Lands. However, also within Rome they didn’t fare much better partly because of some serious misbehaviour and partly because of political infighting between the powerful senatorial families (see Papal Pornocracy). As a result we see the Popes calling on the Frankish rulers for assistance.

This weakened papal position made it possible for Emperor Otto the Great to increase hid power of the Church. In 962 Pope John XII asked the Emperor for military support during one those difficult times. He reinstated the Pope and provided security for the independence of the Papal States. He found himself worthy of the imperial coronation and two days after he arrived in Rome he had himself crowned by the Pope.

The next day he had the pope sign the so called (Diploma) Ottonianum (also called the Privilegium Ottonianum), it confirmed the earlier Donation of Pippin, granting the Emperor control over the Papal States, regularising Papal elections, appoint bishops and clarifying other relationship between the Popes and the Holy Roman Emperors. This document would dominate German politics for the next 300 years, as the Emperors moved their focus away from Germany , instead concentrating on bringing Italy fully under their power, this however, would never happen.

With this agreement under his arms he was able establish his power among the many warring regional nobles throughout his realm. The way he did this was by taking land and power away from these nobles and transfer them to ecclesiastic rulers – especially to bishops (Prince-Bishoprics) – these church positions were non-hereditary and with the Ottonianum he was able after the death of the bishop to simply appoint a new on, loyal to him. This also became the start of the Investiture Conflict, which – at the Concordate of Worms in 1122 – was eventually won by the Pope. However, at least at the start of this period, with his powerful control over the Church, he could exactly do that and transferred large properties to the various bishops in his Empire.

Papal authority was restored in the 11th century. With their new authority the popes started to challenge the ecclesiastic powers that kings and emperors had taken over the preceding centuries. However, throughout the Middle Ages both the popes and the emperors operated within a continuous state of upheaval.

Popes regain religious authority

The collapse of the Roman Empire also undermined the unity of the Church as popes lost their vital communication with their bishops and abbots. They became isolated in Rome where they were under siege of the local feudal rulers, the powerful senatorial families and the counts in Italy. For centuries the popes had very little authority outside Rome itself. It were often sons of kings and other nobles who were made bishop and there were subsequently many prince-bishoprics.

It took centuries to clean up this mess and there was brief survival after Cluniac reforms around 950. It was under Pope Leo IX (1049-1054) that slowly papal authority could be exercised again outside Italy. This happened after the Holy Roman Emperor Henry III, saw the political value of the prestigious papal office. In 1046, the year that there were four poses he used his authority to dismiss three of them and arranged that Clements II received the see. Importantly, he was able to wrestled control away from the Roman aristocratic families.

This led to Investiture Controversy was the most significant conflict between secular and religious powers in medieval Europe. It was a sign of of the Pope regaining its authority and began as a dispute in the 11th century between Henry IV, Holy Roman Emperor, and the Pope Gregory VII concerning who would control appointments of church officials (investiture).

Since the collapse of the Roman Empire the appointment of church officials, while theoretically a task of the Church, was in practice performed by the kings. Since a substantial amount of wealth and land was usually associated with the office of bishop or abbot, the sale of Church offices (a practice known as simony) was an important source of income for secular leaders; and since bishops and abbots were themselves usually part of the nobility that formed secular governments, due to their literate administrative resources, it was beneficial for a secular ruler to appoint (or sell the office to) someone who would be loyal. In addition, the Holy Roman Emperor had given himself the authority to appoint the pope, and the pope in turn would appoint and crown the next Emperor; thus the cycle of secular investiture of Church offices was ensured to perpetuate from the top down indefinitely.

The crisis began when a group within the church, members of the Gregorian Reform, decided to address the sin of simony (see also Papal Pornocracy)by restoring the power of investiture to the Church. The Gregorian reformers knew this would not be possible as long as the emperor maintained the ability to appoint the pope, so the first step was to liberate the papacy from control by the emperor. An opportunity came in 1056 when Henry IV became German King at six years of age. The reformers seized the opportunity to free the papacy while he was still a child and could not react. In 1059 a church council in Rome declared secular leaders would play no part in the election of popes, and created the College of Cardinals, made up entirely of church officials. Since 1179, the College of Cardinals remains, till this day, the method used to elect popes.

Once Rome gained control of the election of the pope, it was now ready to attack the practice of secular investiture on a broad front. However, what in all reality happened was that this renewed vitality led to arrival of the papal monarchy, which would result in a repeat of the situation that had needed these reformations in the first place.

As soon as Henry IV came at age he challenged the pope and demanded back his investiture powers. However, Gregory did win this stand off, excommunicated the emperor and Henry had to make the infamous Walk to Canossa, where standing barefeet in the snow, so the story goes, asking for forgiveness from the pope. The powerfull Matilda of Tuscani, Countess of Canossa was a key negotiator in the three day long stand-off and the negotiations took place in her castle.

As most of Europe and the north-western region was drawn into the conflict and this led to strong division and local wars. This was particularly prominent when the pope called for the first crusade to the Holly Land. Godfrey of Bouillon became the leader of this campaign together with his brother Baldwin. However, most of the nobility in Lotharingia refused to support the pope. They included the dukes of Leuven and the counts of Gelre, Limburg and Namur.

After fifty years of warring over the issue, a compromise was reached in 1122, signed on September 23 and known as the Concordat of Worms (concordats are treaties between the church and a state). It was agreed that investiture would be eliminated, while room would be provided for secular leaders to have unofficial but significant influence in the appointment process. Church appointments were handed over the various chapters linked to cathedrals, however these chapters were largely made up of members of the nobility, this gave the local secular rulers significant influence in these appointments. As an example in the 15th century the Burgundian Duke Philip the Good was able to arrange a bishop position for 32 of his relatives.

The reforms therefore did little to stabilise the authority of the church; secular corruption remained ingrained and large scale misuse of the church privileges were getting worse rather than better. The uneasiness between the Popes and the Emperors would continue for many centuries to come. In the 14th century, writers like Dante Alighieri and Marsilius of Padua were among those who eloquently attacked these situations. Eventually the Reformation fuelled by popular uprisings in the 16th century started to result in some more serious changes.

Already in the 12th century the Holy Roman Empire was able to regain its dynamics under the Hohenstaufen dynasty. Their ecclesiastic powers became also clear when in 1220 Frederick II enshrined in law that bishops and abbots were given legal independence. This made these ecclesiastic rulers full blown territorial princes; a situation that would continue to well into modern times.

A severe weakness was that these bishops and princes became all powerful and often the Emperor ruled only in name, the real power lay by the up to 300 individual counts, dukes, bishops and other princes.

An indirect result of these ongoing conflicts between the emperor and the pope created was an ongoing level of division within the German states and was the key reason why Germany never grew into a country state such as for example was the case with France and England.

Guelphs and Ghibellines

The Guelphs (Guelfs) and Ghibellines were factions supporting, respectively, the Papacy and the Holy Roman Empire in central and northern Italy during the 12th and 13th centuries.

Guelph is Italian for Welf, the family of the dukes of Bavaria. The Welfs were said to have used the name as a rallying cry during the Battle of Weinsberg in 1140, in which the rival Hohenstaufen of Swabia (led by Conrad III) The major Guelph group was led by Henry the Proud in Saxony and his son Henry the Lion, Duke of Bavaria and Saxony.

The Italian name Ghibellines was derived from Waiblingen (Ghibellino in Italian) the name of the originating castle of the Salian and Hohenstaufen kings, in the current region of Stuttgart. They represented the imperial party.

Broadly speaking, Guelphs tended to come from wealthy mercantile families, whereas Ghibellines were predominantly those whose wealth was based on agricultural estates. Guelph cities, of course, tended to be in areas where the Emperor was more a threat to local interests than the Pope, and Ghibelline cities tended to be in areas where the enlargement of the Papal States was the more immediate threat.

In Italy the Lombard League and its allies (Milan, Piacenza, Cremona, Mantua, Crema, Bergamo, Brescia, Bologna, Padua, Treviso, Vicenza, Venice, Verona, Lodi, Reggio Emilia and Parma), in rare events of cooperation, defended the liberties of the urban communes against the Emperor’s encroachments, became the Guelphs here.

Depending on where the cities were situated they were technically vassals of either the Emperor or the Pope in reality however, these towns – or rather their ruling families – were most of the time able to rule independently. They far more often were fighting between themselves than that they were actively involved in the battles between the bigger powers.

The House of Welf

The House of Welf is the older branch of the House of Este (Estensi), a dynasty whose oldest known members lived in Lombardy in the 9th century. For this reason, it is sometimes also called Welf-Este. The first member of this branch was Welf IV; he inherited the property of the Elder House of Welf when his maternal uncle Welf, Duke of Carinthia, died in 1055. In 1070, Welf IV became duke of Bavaria.

The division between two distinct “Guelph” and “Ghibelline” parties became defined during Frederick Barbarossa’s reign, when he invaded several parts of Italy between 1150 and 1180. He loved Italy and spend a large part of his life here, but generally didn’t venture any further than Rome or Naples. It was the resistance of the Lombard League – supported by the Pope – that alluded him from dominating the Italian peninsula. Frederick died suddenly in 1190 during the Third Crusade.

The son of Frederick and his wife Beatrice of Burgundy became Emperor Henry VI at the age of 4, he was born in Nijmegen. He married Constance Queen of Sicily, a descendant of the Norman Crusader Tancred. This allowed Henry VI to also add Sicily to his empire and also extended his powers in southern Italy. He united all of his processions – including those in Italy – into a greater Germany. In response the Pope extended this power of the Papal States in central Italy.

The next Emperor, the in Sicily born Frederick II, had a difficult start of his reign. He was 3 years old when his father died. And the succession became an international conflict with France and England both becoming involved in the factional divisions with Germany. In the end the French King Phillip II – supported by Pope Innocent III – successfully defeated Frederick’s opponents at the Battle of Bouvines in 1214. These events resulted in the other European powers now also becoming interested in Italy.

Frederick II

Innocent was central in supporting the Catholic Church’s reforms of ecclesiastical affairs through his decretals and the Fourth Lateran Council in 1215. This resulted in a considerable increase in the Western canon law. He is also notable for using interdict and other censures to compel princes to obey his decisions, although these measures were not uniformly successful, it clearly established the leadership aspirations of the Church.

One of those ‘princes’ who didn’t accept the pope’s supremacy was the new Emperor Frederick II who believed himself divine in virtue, not just of his office but also of his inborn nature. He certainly was one of the most successful Holy Roman Emperors and under his reign Sicily became the most sophisticated state in Europe with a well organised government with an excellent navy, successful trade, high cultural life; it became the cradle of Italian medieval poetry. He also established the State University of Sicily, the first one in Europe not established by the church. He had grown up on the streets of multicultural Palermo and spoke 6 languages: the Sicilian dialect, German, Latin, Greek, Arabic and Hebrew. He was continuously at odds with the Papacy (he was excommunicated four times, once during during the Sixth Crusade because he was too friendly with the Arabs see: Crusades). Also Frederick II took on Lombardy, but like his grandfather was in the end defeated by the Lombard League.

Frederick had this Castel del Monte (Apulia, Italy) build based on a geometric design that is unique. The fortress is an octagonal prism with an octagonal tower at each corner. The towers were originally some 5 m higher than now, and they should perhaps include a third floor. Both floors have eight rooms and an eight-sided courtyard occupies the castle’s centre. Each of the main rooms has vaulted ceilings. Three of the corner towers contain staircases. We visited the castle in 2016.

Before the crusade, Frederick II founded the University of Naples and met the great mathematician Leonardo Fibonacci, who introduced the Arabic numeral system in Europe. This does not explain the obsessive repetition of the number eight in the construction of Castel del Monte, but it has led historians search for a concealed meaning. The figure eight has been seen as a symbol of infinity and resurrection, and they have even pointed out that shadows in the octagonal courtyard form the Golden Ratio used in the Fibonacci Sequence.

The German hegemony in Italy finally ended under Emperor Conradin who in 1268 was defeated at the battle of Tagliacozzo by an army of allied forces. This ended German rule over Italy and also ended the Hohenstaufen rule, as a mere four years later Conradin was beheaded (see below). It also ended the Hohenstaufen ambition to recreate the Roman Empire. Papal authority howevcer, was not restored as the popes had to flee Rome and settles in Avignon (see below).

Upon Conrad’s death the Great Interregnum began, lasting until 1273, one year after the last Hohenstaufen, Enzio, had died in his prison.

Another important event in the ongoing quarrels in Italy was that the Sienese Ghibellines inflicted a noteworthy defeat to Florentine Guelphs at the battle of Montaperti (1260). After the Guelphs finally defeated the Ghibellines in 1289 at Campaldino and Caprona, they began to fight among themselves. By 1300 Florence was further divided into the Black Guelphs and the White Guelphs. The Blacks continued to support the Papacy, while the Whites were opposed to Papal influence, specifically the influence of Pope Boniface VIII. Dante was among the supporters of the White Guelphs, he participated as a feditori (member of the elite corps) in the battle of Campaldinio in 1289 where Florence defeated Arezzo. When the Black Guelphs took control of Florence in 1302 Dante was deprived of his property and exiled, accused of anti-papal activities. Were he bitter and sick died 19 years later. In 2007 we visited the Dante Museum (Casa di Dante) in Florence where the conflict, the battles and Dante’s position in the conflict is on display.

The broader conflict did spread like wildfire through Europe and was used in many conflict, most of them with very little direct link to the original conflict.

In the Low Countries, after the death of prince bishop of Utrecht, Otto II of Holland, the conflict was used in the election process of the next bishop, on one side the majority of the canons of the Chapter on the other side a minority of them supported a Welfisch proponent, however they had the support of the Archbishop of Cologne and the Pope. While the Hohenstaufen did win the first round their bishop Gosewijn of Randerath was forced to resign a year later and the Welfish Hendrik van Vianden became the next bishop (1250-1267).

In the 15th century the Guelphs supported Charles VIII of France during his invasion of Italy, while the Ghibellines were supporters of Emperor Maximilian I.

Military Ghibelline leaders in Italy, started to turn into dictators, assisted by their mercenaries (equitatores) they took over local power and gave themselves titles such as Duce (Duke) and marquis. They formed formidable dynasties such as the Visconti’s in Milan, Scaligeri in Verone, Maltestas in Rimini, Montefeltros in Urbino.

Cities and families ruled here until Emperor Charles V firmly established imperial power in Italy in 1529.

Emperor against Pope

After the death of Frederick II the pope used the opportunity to ignore the will of the Emperor to pass the crown on to his infant son Conradin. This attracted other European again to the Italian theater.

Completely ignoring Conradin’s rights Charles of Anjou and Pope Urban IV, in June 1264, came to terms over a contract to sell the crown to Charles, a brother of King Louis IX of France.

However Urban died while only an unsigned draft had stated the terms. In 1265 Charles renegotiated the terms with Pope Clement IV, who was being hard pressed in the Guelph (see below) cities in northern Italy and Rome itself by Manfred of Sicily, a bastard of Frederick by Bianca Lancia. Manfred had fought his way to the throne during the interregnum, but had sent ambassadors to Germany announcing that he recognized Conradin as his king.

Nevertheless, Charles was solemnly invested by the Pope with the Kingdom of Sicily.

The Night of the Sicilian Vespers – 1282

In the ensuing war for control of the Sicilian Kingdom, Charles would win important battles at Benvenuto against Manfred, and at Tagliacozzo against Conradin. Not being satisfied in conquering all armies laid against him, he set out to make an example. Conradin had escaped the battlefield at Tagliacozzo, but had been apprehended shortly thereafter and, contrary to the custom of the time, Charles placed him on trial for treason against his lawful king, using as a pretext his invasion of the Sicilian Kingdom. To the horror of all of the European nobility, on 29 October 1268 the sixeen-year-old Conradin and his main followers were beheaded in the public square in Naples.

Charles’ Italian and Sicilian subjects were shocked and took note that their new king would be merciless. Charles moved his capital to Naples from Palermo and to the people on the Island of Sicily, he continued to show his merciless attitude by naming abusive Frenchman to rule there as justices, tax collectors and bureaucrats. After many years of high taxes, rape, theft and injustice, the Sicilian people rose as one on the Night of the Sicilian Vespers (named after the sunset prayer marking the beginning of the Night Vigil on Easter Monday, March 30, 1282) whereby, throughout the island, most of the French on the island were massacred. In Erice this happened outside the city gate Porta Spada (see video clip).

The islanders initially tried to negotiate a ‘Free Commune’ status under papal suzerainty, however the French Pope Martin refused but the Sicilians persisted.

Both Charles and Clement had also ignored that there was another lawful heir in the line of succession, Constance of Aragon, Manfred’s daughter who at the time of Conradin’s death was married to the Infant Peter, the son of King James of Aragon.

The rebels now sent for Peter III of Aragon and he successfully championed his wife’s claim to the entirety of the Kingdom of Sicily. In August that year he landed in Trapani (video clip).

He made a promise to the islanders that they would enjoy the ancient privileges they had had under the Norman King, William the Good. Thereafter, Peter was accepted as a satisfactory second (after the ‘Free Commune’) choice and was crowned by acclamation of the people.

It also interesting to put this event in the realpolitik of the time. Charles ambition was to use his Sicilian stronghold to conquer Constantinople and at the time of the rebellion he had assembled his fleet in Messina. However the rebels had burned the fleet and thus the attack was diverted. In the running up of this the Byzantine Emperor had financed Peter III ‘s fleet who happened to be at the appropriate time in the neighbourhood.

By 1300 the grip the Pope had built up over the previous 250 years on European affairs started to wane. Instead the local churches started to become more powerful in relation to political influence, but equally the local kings became more influential in their national churches.

For more information on developments in Italy see also:

Italy and the Papal Pornocracy 800 – 1100

The papal court moves to Avignon

So at end of the 13th century Papal power at Rome was at a near collapse. This situation came to a breaking point in 1294 when Pope Boniface VIII became pope and immediately placed himself above the world and claimed that the highest power in their world resided with him and with him alone. The action was mainly aimed at the French king Philip the Fair.

The French king decided to remove the Pope from office, he was captured but also soon released but died shortly afterwards. A combination of events that happened in this period led in 1309 of the removal of the papal court to Avignon by the next pope Clement V. Interestingly Avignon was then part not of France, but part of the county of Provence, which was part of the German Emperor and held in fief by the king of Naples.

The move however, has to be seen against the background where Clement V wanted to repair the relationship with the French king.

Holy Roman King Henry VII had himself crowned Holy Roman Emperor, but failed to establish his authority in (northern) Italy. His successor Louis of Bavaria did the same but was even less successful of reinstating Rome as the Holy Roman City.

Eventually some of the differences were put aside and in 1377 Pope Gregory XI returned to Rome. However, after his death the following year a great schism occurred when the election of a new pope resulted in the election of a new pope followed by a retraction of him and elected an anti pope who set up court in Avignon.

The Great or Western Schism resulted in serious political problems throughout Latin Europe as the various rulers had to chose which pope they would support. France and its allies (e.g. Naples, Spain, Scotland and Burgundy) choose for Avignon and the rest of the region for Rome. England was fiercely opposed to Avignon as the country was at war with France at the time.

Under the leadership of Emperor Sigismund the Council of Constance (1414 – 1418) was established to solve the schism. The Council was at that time the largest public European gathering ever and all nobles as well as ecclesiastic participants were allowed to vote. The sitting popes were forced to resign and a new pope Martin V was elected and ruled from his court in Rome.

Conflicts between the pope and the secular rulers continued as was evident when Emperor Charles V imprisoned Pope Clements VI during the sack of Rome in 1527. It was not until after the Reformation that finally changes started to occur that resulted in a more clearer separation between religion and state.