Monotheism

We have seen in ‘Early beliefs, paganism and religion’ the transition from a more egalitarian social system (sometimes not totally correct referred to as a matriarchy) to a more male dominated paternalistic system. Most Neolithic societies are thought to have been more egalitarian than the later Bronze Age societies. It has been argued that this also resulted in a change form a more feminine centric belief system (Mother Earth Concept) to one based around a Sky Deity. This latter led to to the development of a belief system built around the tripartition of the society. From here on we see the power of cities and the city elite who gradually take onboard the role of God and combine secular and spiritual powers into the one person (king, pharaoh, shah, etc).

However these city states and empires were still surrounded by tribes with religious believes still very much around the Sky Deities. We also see in these new urban societies that often one god became the main god and that this deity had some sort of a superior position over the other gods and goddesses, this religious concept is known as henotheism.

We also now see the arrival of the Sumerian/Babylonian tradition of city gods. Several of the early city states had created their own senior deity that held such a position and this often made it easier for the king to take on that god position himself.

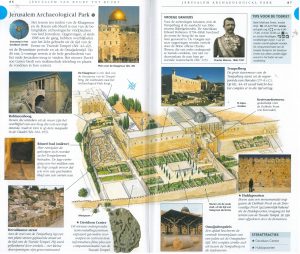

While the mythical Abraham of the Jews – the first one to worship one God – is placed around 2000BCE we don’t have any archaeological evidence of these people until the first millennium BCE. The Jewish mystical tradition, the Kabbalah, also dates back from these times. Abraham is not only seen as the founding father of the Hebrews but also of the Muslims and the Christians. He came from Ur and worshiped his city God and this city god travelled with him on his trip west towards the ‘Promised Land’.

Not far from here, in Egypt, we see around 1300BCE , pharaoh Akhenaton forcefully introducing monotheism in Egypt around the God Aten. Akhenaton means server of Aten, however this religious concept didn’t stick in Egypt.

Back to the Israelites, and around 800BCE we see the arrival of the Judaic tradition of monotheism. However, on a a tomb inscription from 563BCE (before the destruction of the first temple) there still appears Yahew together with Ashera. However, after that time no more ‘idols’ appear.

It is uncertain how monotheism developed into such a strong movement, but perhaps the explanation simply is that all human beings do have a strong individual spiritual notion and that therefore deep within the human nature we reject the power of another human being or system (king, empire) over our minds.

This obvious will have been assisted by the clear evidence to most people at the time, as it is to us now, that power often corrupts and that these king gods mostly didn’t behave in a godlike fashion.

The concept of monotheism, whereby its believers did not accept that the secular rulers had power over their mind, didn’t sit well among these rulers. The Jews rapidly became one of the most prosecuted people, the Hittites, Babylonians, Egyptians and Romans all faced these stubborn Jews. The poor Jews were most of the times no match to these far more powerful neighbours and suffered the consequences of their strong believe. But despite all of this their believe system survived and through Christianity and Islam monotheism became the most powerful form of religion over the following 2500 years.

Famously Jesus, according the Bible, answered when he was asked about who is charge: ‘Give the Emperor what belongs to the Emperor and to God what belongs to God.’

While under Charlemagne the secular and religious powers were once again brought together it rapidly became an ongoing power struggle between the emperors and popes, this despite the fact that a key element of the original Christian tradition (based on Greek philosophy) was that there should be a separation between Church and State. It was seen as a fundamental human right that one should have total control over his or her own mind. While the Investiture Controversy made some changes to that situation it still would nearly take a millennium before full separation was achieved.

While monotheism became the dominant religion many aspects of the early (pagan) religious concepts are still clearly visible even within the current religious versions.

The small nomadic tribe of the Israelite

A rather small Indo-European tribe, living in an environment surrounded by very powerful empires tried somewhere between 2000 and 1500BCE to find a land where they could settle and become farmers. In an area wedged between the sea and the dessert, arable land comes at a premium and many others were interested in that same piece of land. Despite persecution, massacres and exiles this small tribe survived against all odds most likely because of their strong cohesion, sense of community, tradition and devotion to one God, very importantly their God. They claimed they received their Law via Moses directly from their God and this allowed him to obtain obedience from his people this belief assisted the tribe to maintain a peaceful society in pursuit of their own country.

They outlasted many far more wealthy and powerful empires. Their strong conviction of being ‘the chosen people’ was used to occupy – around 1500BCE – the land of Canaan – as this was promised by their God to Abraham. This promise was an endorsement to aggressively fight with other tribes in the area in order to claim this land theirs.

The history and law of these people was, similar to other peoples from around that time, in the hands of the poets. It is estimated that some of the stories that are, in what is known as the Bible, dating back to around 1000BCE. The Ten Commandments are also dating back to this period and are a set of ethical rules, a code of morality, based on justice for all. Scholars recognise several different authors and different periods. The three main sources are: The period of David and Solomon (known as the J source), Joshua (D) and the writers of the Babylonian period (P).

Most likely this – from origin Jewish culture – would have disappeared in obscurity if it wasn’t for the reason that the far more sophisticated and advanced knowledge of that time developed by the Greek was lost in the West. The Greek had taken the rather archaic and primitive culture of their own nomadic forebears and developed a much more modern society. However, between 200 and 600AC this wealth of knowledge was lost in the West. Christianity and later also the Islam started to fill the vacuum left.

Transition from Jewish sect to Christian religion

The Christian concept of a single God, eternal salvation for the faithful and victory over death was certainly not unique at that time; there were many sects that had similar concepts. Christianity was of course originally a Jewish sect, and operated as such – as one of the different forms of Christianity. It also basically appropriated most of the Jewish religious texts, so in all there was nothing much new that was invented in that respect. Similar to the above mentioned pagan adaptations, also many of the Jewish traditions became an integral part of Christianity.

In the beginning the apostles simply preached their message of the gospel and the messiah within the context of Judaism; basically heralding a new era, a modernisation.

At this stage there was not a divide between – what later became known as orthodox Christians and heretics. There were certainly different views in those early period which existed alongside each other and over time they influenced each other and slowly further common themes arrived in a very dynamic process of discussion, exchange and eventually more formal approaches. A process also sometimes known as ‘identity formation’ .

The three main groups were the Jewish Christians, Gentiles and the Gnostics, but also within these groups there were differences based on social, cultural and geographic elements. The central themes included: Jesus, the crucifixion and salvation – not necessarily all in the same combination with each other – but most other elements were at stage open to interpretation.

They were able to link very general (catholic in Greek means general) ethics such as ‘thou shall not kill’, ‘thou shall love their neighbour” and elements such as looking after the poor and the weaker people in the society to their more religious beliefs. The early Church also showed itself far more tolerant to women and slaves than most of the other cults.

The first split occurred with the orthodox Jews who wanted gentiles (which included Greeks, Romans and Arabic people) – who were attracted by the new teachings – to follow the Law of Moses.

St Paul preached a more modern version that didn’t require circumcision and certain other elements of the Law, in particular in relation to food and with whom to share food. Apostles like Peter and James (Jesus brother) wanted the converts to strictly adhere to Jewish Law; Paul who mainly preached among gentiles was far more flexible.

Some of these issues were resolved at what is believed the first Council which took place in Jerusalem around 50CE.

These internal conflicts however kept festering on, but when the Romans destroyed the Temple in 70 and the Jewish Diaspora started this split more or less automatically happens. Withe their land lost the only element the Jews could maintain was their religion. They were understandably very protective of this and therefor the Jewish religion remained closed and exclusive, while its new brand Christianity was more open and (at least in the beginning) more tolerant. A definite split occurred somewhere between the years 85 and 89. Obviously this didn’t happen without pain and anger and some of the results of that conflict became also part of the language used in the gospels that were written around that time.

The seeds for further conflicts between the Jews and the Christians can certainly be traced back to these turbulent years.

It was under the zealous leadership of St Paul that the Christian Church started to emerge. He traveled far and widely and most probably had the greatest influence on the shaping of the Catholic Church and its religion. He also was the one who created the distinction between Christians and ‘others’ a theme that was picked up in the Middle Ages for discriminatory reasons. Paul was also discriminatory towards women and this was taken up by the church and is still a hotly debated issue in modern times.

He single-handed transformed the historical Jewish Jesus into a mythical hero. Karen Strong argues that historical events need to be mythologised in order for it to become a source of religious inspiration [1. Karen Strong, A short history of myth, 2005, p106] . This also further described in the section ‘Early beliefs, paganism and religion’.

Key elements said to be added by Paul to Christian theology.

They include:

Source: Tom O’Golo (2011). Christ? No! Jesus? Yes!: A radical reappraisal of a very important life. p. 81. |

From its early beginnings Christianity was a literate religion, which allowed it to spread more easily. The early Christians formed their own communities, the organisation was done by the elders. Rather earlier they already had priests (presbuteros-elder) or bishops (supervisors)leading the service. During the 2nd century bishops gradually became the supervisors over the priests, they nearly always settled their bishopric within the Roman civitas. This process rapidly accelerated after Christianity became the Roman state religion A bishop was elected by both the ecclesiastic and secular members of his communities. With the spread of Christianity and the increase in its organisation, slowly these two parts became more separated. The ecclesiastic members became exclusively in charge of the religious activities, especially after the concept of sacraments started to take roots. Baptism was a well established initiation rite that was also used by the early Christians and the early meals they shared together, became more formalised after excesses started to occur and regulations were introduced with evolved in the Eucharist.

Many of this early doctrine linked in very well with human faith and as such as easily accepted by the people. Over time more and more of this faith became institutionalised into religion. Problems started to occur when the gap between faith and religion started to grow to such an extent that people concluded it had very little to do with their faith.

It is remarkable to see how modern the writings of these early philosophers are in comparison to some of the discussions that are taking place on this topic in the 21st century.

During the 1st century the Middle East and North Africa was the heartland of early Christianity (Syria, Egypt, Ethiopia).

Mixing of religious concepts and traditions

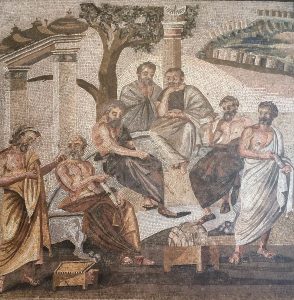

The evolving Christian doctrine was as much based on the Bible ( a library of diverse documents) as it is on globally accepted moral codes such as they were discussed in the works of the Greek philosopher Plato. The early Church fathers used the works of Plato and Aristotle as a basis for the Christian doctrine they started to develop. Especially the role of the soul made the Greek close allies of the Christians. Also the Greek had been the first to – thanks to the invention of writing – to move from pagan mythic to theory and this was further developed by these great philosophers into a top down approach of conceptual hierarchies, which very much suited the new religion. Knowledge rather than faith was a key element of the Greek philosophers and particularly under St Augustine the roads started to depart here, as he believed that grace and faith were the roads to salvation rather than knowledge.

All of this knowledge was in Greek and Latin and as such not accessible to 99% of the population. This in contrast to the Quran which was written in the vernacular and was therefore easily accessible to his followers.

Platonism

This is not a religious concept but it had enormous influence on the early Church and later on during the Middle Ages. Plato’s thoughts were seen as being closely related to those of God and as such – while a pagan – Platonism was – most of the time – very well accepted by the Church.

The Church Farther Augustine started of as a Platonist. It is a philosophy based on the works of Plato. He believed that knowledge/reason/education could overcome evil rather than faith and that of course created the impossibility of it to become a religious concept. Central to this philosophy is the distinction between ‘reality’ which is perceptible, but not intelligible, and that which is ‘intelligible’, but imperceptible (soul). Plato theory is based on ‘Forms’ and the highest form is identified as the Form of the Good, the source of all other forms. Both ‘reality’ (material”) and ‘intelligible’ (spirit/soul) are good but the spirit is the higher Form.

Under Plotinus mystic elements were added to this – Neoplatonism – and here the soul had the power to elevate itself to attain union with the One.

One of the most interesting concepts the Christians took over from the Jews was that of the Messiah. A name that originated in Mesopotamia and had a secular meaning along the lines of: leader, king, saviour. While the Jews see their Messiah as the future new King David (and are still waiting on him), the Christians (Khristos in Greek means messiah) believed that Jesus was the Messiah.

Both religions talk of a Messianic era, once the Messiah returns (Christians) or arrives (Jews) there will be a millennium of peace. The theological belief of chiliasm or pre-millennialism (where an Antichrist would be defeated which would lead to a world of peace, plenty and happiness for the poor) describes the period that will herald the coming of the messiah. This is described in a body of text known as eschatology (a set of church doctrines concerning the final state of the world), based on the prophecies in the Book of Revelation. This concept had entered the Catholic and Jewish faith via the Babylonian and Persian concepts of eschatology.

These doctrines dominated people in the Middle Ages. At regular interval a new ‘messiah’ was spotted sometimes it was a zealot, at other times a king, they all fitted nicely into the eschatology fantasies.

We also find these chiliastic fantasies back in art (Jheronimus Bosch), the Crusades, and many of the so called heretical movements, they were heavily influenced by this believe. While the Church, most of the time, tried to play down the physical interpretation of these eschatology doctrines and indicated that they were of a more spiritual nature, they most of the time failed to convince the people.

Only very slowly during the Age of Enlightenment do we see these concepts losing their momentum. However religious fanaticism, ideological fanaticism and fascism all have elements that are related to these medieval ideas and practices.

Furthermore concepts that we now classify as Christian were borrowed from Egypt and the Middle East such as common meal rituals, purification, fasts, the concept of immortality, that transmigration of souls and initiation rites. Buddhism also has the concept of the Immaculate Conception.

During Roman times we also saw the Cult of Mithra (Mithraism) briefly becoming the official state religion. Mithra was originally a Zoroastrian Deity which was likened by the Romans as God Sol (Sun). Zoroastrianism dates back from well before the 6th century BCE and Zoroaster was the Persian prophet who preached this new religion. Zoroastrianism became the state religion in Persia and sometimes referred to as the bridge between mythology and philosophy.

Mithra is not seen as an official part of monotheism, however it looks like certain elements of the Mithra Cult (as well as Zoroastrian religion) did find their way into Christianity. Mithra stood for the celebration of light (Sol) and was celebrated in December (Sol Invictus) which later became Christmas. Zoroastrian eschatology and demonology, with its concepts of angels, satan and hell, also made its way into Christianity. As well as the concept of ‘Virgin Birth, ‘Holy Spirit’, the ‘Judgement of the Dead’ and the ‘Resurrection of the Body’. Scholars also suggest that Zoroastrianism influenced the Hindu and Buddhism religions.

Mithraism entered the Roman Empire around 70BCE and was in particularly followed by Roman soldiers. There were also temples (Mithraeum) in the northern region. There was one in Sarrebourg, near Metz and some of it has been restored and is now on display in the Court D’or museum in Metz. They only found remnant of such a temple under the church of Elst.

This religion disappeared, once Christianity started to take hold in the Empire.

Another interesting link with pagan elements is that the Celtic god for light, Lugh was speared in the side by a spear similar of Jesus and Lugh as well as the German God Odin were hanged on a tree similar to Jesus on the Cross. Many pagan religions have spearing in their stories, often related to the taboo of incest. (The Australian Aboriginal Deity Daramuluun was, for that reason, speared in the leg). Dying and rising Gods are also known in the mystery cults of Osiris, Attis and Persephone.

While Christianity was well received in the cities around the Mediterranean, it was resisted by the rural population especially the further you got away, north of Rome. Interestingly also the the top layer of Roman society (Senatorial families) resisted Christianity but in their case this simply had to do with a threat to their power. Also many of the intellectual and more educated people – namely the philosophers and their followers – resisted Christianity as they believed in reason over faith.

With Christianity further moving north, many Germanic pagan traditions were hard to suppress and the Church changed tactics by turning many of these traditions and celebrations into Christian events. Temples and holy pagan sites became places where Christians congregated and many of these places were used to built the first (wooden) churches. With a growing number of saints it was not to difficult to replace the many pagan gods and their holy days became the holy days of the saints, in that process these saints also often took over the attributes, symbols and features of those pagan gods.

The Bishopric of Utrecht had during the Middle Ages, 57 holy days, where people were not supposed to work unless strictly necessary.

The pagan festivals were closely linked to the growing seasons and the solar and moon cycles. Many of these festivals were replaced with Christian symbols

- Easter – spring festival

- Whitsunday – summer solstice

- Christmas – winter solstice (Yule)

- Other festivals linked to the harvest include St John (24 June), Maria Ascension (15 August), St Martin (11 November).

Another observation is the role of art in this process of communication. While the Ten Commandments forbids idolatry, it did find a way around it by claiming that Jesus had lived a human life on earth and that therefore images were OK.

While beauty could be interpreted as vanity, in this religious context this was OK as its purpose was to invoke contemplation. Christian art is decorative, initially this was expressed in the manuscripts that are beautifully and elaborate decorated, they were only used by monks and nuns and these manuscripts were much more than books of knowledge, also more than just celebrations of Christ, the Saints and the Church, they were gateways to heaven to eternal live. Later paintings that adored the churches had a similar value to please God, but they also provided information and education. The same applied to architectural sculptures in cathedrals and the cathedral itself was the House of the Lord and as such a gateway to heaven. Medieval people’s thoughts were distinctively different from those of people living today. Manuscripts, art and architecture had several totally different levels of meaning, which was very well understood by medieval people.

See also video clips:

Jerusalem Church of the Holy Sepulchre, Jerusalem Via Dolorosa, Galilee, Israel

Monastery St Agatha Netherlands (Manuscripts)

Monastery Ter Apel Netherlands

Persecution of Christians

Increasingly Romans became dissatisfied where their traditional religion and many looked for more personal forms of religious experience, the most well know were the religions of Isis (ritual purification by water) , Mithras (sharing ceremonial meals with bread and wine) and Cybele (annual feast of resurrection in spring). They were known as mystery religions their rites were not open to others and as such were seen as mysterious in the eyes of the official Roman religion. Christianity was seen as one of these mystery religions. The problem that the Roman authorities had with the emerging Christian mystery was that unlike all the others was that this one was strict monotheistic and unlike all of the other cults didn’t accept the umbrella function of the veneration of the Emperor.

These prosecutions started in all earnest in 64 when Emperor Nero blamed Christians for the fire that devastated Rome, during his rein also Peter and Paul were crucified.

In January 250 Emperor Decius issued an edict declaring that all citizens have to sacrifice to the gods. As Christians only recognised one god, they would not sacrifice, thus persecution started again. Christians established church houses, mainly in the poorer areas. Catacombs were used for burials as cremation was not part of the religion. This period of prosecution cumulated under Diocletian (Great Prosecution 303-311).

However, the situation wasn’t the same throughout the Empire and in particular in the East, from the 2nd half of the 3rd century the situation started to improve for the Christians. This might also be a period were some of the first church buildings started to emerge – mainly in the eastern part of the Empire.

Until approx 310 Christians were still persecuted throughout the Roman Empire and there was little opportunity to establish official structures. However, as in modern day, persecution only hardens the core of the movement and the slain martyrs were adored as heroes. Nevertheless it was estimated that by this time 20% of the Roman population were Christians.

Martyrs – the heroes of Christianity

Anybody who fell in these religious battles became a martyr. Especially the very first martyrs – when the Christians were still persecuted – strengthened the small and tight nit early community. They became the heroes of their age and were, similar to current heroes, adored. The relics (reliquiae) and graves of these martyrs were venerated.

A famous observation from Tertullian – one of the early Church Fathers who lived around 200 – was that, “the blood of the martyrs is the seed of the Church.”

The martyrs became an important symbol of the Christian victory and as such also as symbols of the power of the spirit over the body. When the religion became the state religion there were no new martyrs any more and it after that time that the concept of saints slowly developed, Christian heroes were needed to maintain and grow the religion. This concept neatly assisted the transformation of the many pagan cults and pagan god heroes and many saints took the place of old pagan traditions and symbols.

The graves of these saints were venerated and people gathered at the site to remember, especially the anniversary became a popular event and many churches were subsequently built over these graves. Christian believed in a direct link between the remains and the spirit of saints. The St Peter Basilica in Rome is most probably the most well known of these churches. The Eucharist at these places was seen as being more effective. Being buried close to a saint was another much sought after situation. This obviously could only be afforded by the nobility, who sometimes even build their own mausoleums around such a (presumed) site. As a follow on from here, this made their relics very valuable and this made the trade in these remains one of the most lucrative of the Middle Ages.

Initially few of the martyrs were saints; however they were rapidly fast-tracked into sainthood, without the checks, set out by the Church, which would normally have to be undertaken in establishing saints. Surprise, surprise it were mostly abbots, bishops and devout noble ladies who became the next to be venerated, after the martyrs, they became the next generation of saints. The full process of canonisation was not established until around 1235 (this is still in practice).

From religion to political power

The conversion of Roman Emperor Constantine was the turning point point for Christianity. This gave the new religion the backing needed to become a world religion. Under the Edict of Milan issued by the Emperor in 313, the Christians received their freedom of worship and this brought doctrinal unity to the faith .

Key elements included:

- A reversal of the Diocletian persecution into tolerance

- Return of confiscated property

- Freedom from taxation

- Use of the imperial communication system (empire-wide horse relay network)

- Building of two new basilicas in Rome St Peter and St John of Lateran (outside the city walls)

- Paganism remained allowed

He moved, in 325, the capital of his empire from Rome to Constantinople. It was not far from here in Nicaea (modern day Iznik in Turkey, close to Diocletian’s capital Nicomedia) that he called the first Church Council together. Until the 9th century all such Councils were convened in the Middle East; such had been the impact of St Paul on the region.

While Diocletian had proclaimed himself a God, Constantine didn’t follow him however, he clearly took on the political leadership role of the Church, he chaired the Council of Nicaea, became involved in implementing Christian doctrine, issued judgement on church affairs and mediated in heresy issues.

This created a conflict of interest in so far that the Church had been concentrated on the spiritual affairs of individuals, this now became linked to state administration and to political and commercial interests. This intermingling of state and church interests would continue for more than 1200 years and in some places even much longer.

At this stage there was not yet an established religious leadership in place, the Church affairs were managed by the collective of bishops present at a Council. The Pope hadn’t any leadership role as yet.

Around 360 Emperor Julian the Apostate, while guaranteeing freedom of religion – he was a philosopher and a pagan most likely following Neoplatonism – re-established the pagan religion and limited the power and influence of the Christian nobility in state affairs. However, he only stayed in power for 4 years and it all reverted back to the intermingling of the interests again after his short reign.

Christianity became the Roman state religion under emperor Theodosius I between 379 and 395 and it now enforced the total unity between state and religion and Christianity became the core power of the empire.

Conversation now became a rather military operation and in subsequent centuries groups of people throughout Europe were forceful converted to Christianity.

With the financial and military support of the Emperor behind them the Church could now proclaim its authority over the various flavours of Christianity and as such established as what became known as ‘orthodox Christianity’ and basically anything else became heresy and with the military power behind them these heretics could now be prosecuted.

Bishops became state financed authorities and it were mainly those from the senatorial families who were appointed in these positions. They also adopted the same system of patronage that existed among the Roman elite, they build palaces and supported artists, financed beautification projects as well as infrastructure development. During the decline of the Empire they were often the only form of social and political structure that was left in a city or region.

The stellar rise of Christianity can also be measured in numbers. Under Diocletian perhaps 20-30% of the Roman population was Christian, at the death of Constantine this had risen to 50% and in 390 (Theodosius) an estimated 90% had been Christened.

Another indication of the size of Christianity is that for the Nicaea Council in 325, Emperor Constantine had invited 1,800 bishops, 1,000 from the East and 800 from the West (some 300 of them attended – including closest to north-west European region – the Bishop Nicasius from Dijon).

For the first time Christian thinkers could rise to prominence and these ‘Church Father’ became instrumental in the formation of the Catholic faith and religion. Apart from the early church meetings, this extra level of intellect was added to provide the foundation for this new religion. Their influence persists until today. They built on the works of the Greek philosophers who among other things promoted the idea that memory was a key tool to obtain knowledge. This is sometimes also called a memoria-culture built on remembering, commemorating, memorising, considering and forgetting. This was used in the teachings of the Church as key tools to shape people and society. The Church also considered that the minds of simple people should not be overfed with knowledge and only provided sparsely. Even at the beginning of the 20th century in Oss local folklore had it that there was an arrangement between the Dean of the catholic community of the town and the local catholic industrial margarine magnate . “If you keep them stupid, we keep them poor’.

Church Fathers

| Latin Church Fathers: Ambrose of Milan 339 – 397

Hieronymus 347 – 419 Augustine 354 – 430 Pope Gregory the Great 540 – 604 Byzantium/Greek Church Fathers Basillius the Great 330 – 379 Gregory of Nyssa 335 – 394 Gregory of Nazianze 330 – 390 |

From church house to basilica

Under the stewardship of Constantine the rather primitive church houses started to be turned in to stone churches. They were based on the Roman basilica, these were large roofed halls erected for transacting business and disposing of legal matters. Such buildings usually contained interior colonnades that divided the space, giving aisles or arcaded spaces at one or both sides, with an apse at one end, where the magistrates sat, often on a slightly raised dais. The central aisle tended to be wide and was higher than the flanking aisles, so that light could penetrate through the clerestory windows. Constantine’s design of the new church had a centre nave with one aisle at each side and an apse at one end: on this raised platform sat the bishop and priests. The first one was built at his palace complex in Trier.

The promise of the idea of eternal life was very important to the general Roman society, so Christianity, which uttered this promise, became a real option – anybody can become Christian and attain eternal life! This is contrast with other cults/religions, which were exclusively available to certain groups (men, merchants, soldiers, etc).

Byzantine Church

Also know as the Eastern Orthodox Church,Orthodox Church and officially now the Orthodox Catholic Church.

From its early beginnings at a time when central church authority was still not very well established and the church in the east from the beginning became a blend of Roman, Greek and Orient cultures and over the centuries more a blend of Greek and the Orient.

After the collapse of the Roman Empire in the West, the Byzantine church and empire became more intertwined and greater authority was exercised by the emperor. For example it was the emperor who regulated Byzantine Christian art, the regulations were rigid and limited the development of this form of art. While in the West Church art was used to educate the flock, in the East it was used as an aid to worship. Similar dogmatic limitations applied to religious texts, beliefs and traditions. This has lead to the connotation that ‘Byzantine’ still has.

Nevertheless it was not until 1054 before the Eastern and the Western branches of the Catholic Church finally separated, the schism was triggered by disputes over doctrine, especially the authority of the Pope in far away Rome.

Christian superiority

The new religion rapidly took the next step and simply hijacked the Jewish concept of the ’chosen people’ and from that time onward they proclaimed themselves as ‘God’s chosen people’. Until that time the often prosecuted Christians had showed themselves to be tolerant towards other religions and sects and it had distinct anti-authoritarian elements. However, once ‘in power’ that rapidly changed and they became an aggressive and rather militant religion with little tolerance for anybody who would not follow the religion to the letter of the word as proclaimed by the pope or the emperor – the angry God of the Jews had very little time for people who would make mistakes as was also very clear in many of the Bible stories.

The Christian model was based on the teaching of Jesus and it was St Paul who remodelled Judaism in order to give it a broader appeal. A key attraction to the emerging new religion was that God would forgive all the sins of the faithful and would this save them eternal damnation. There was a huge emphasis on sin which allowed the religion to built on that to formulate rights and wrongs that would lead to salvation or damnation. The formulation of this new religion happened at the time that the more learned Greek and Roman civilizations started to disappear. Christianity also had a strong militant element to it. Paganism and heresy could be punished by death, similar to God’s Promise to the Jews’ this was seen as an endorsement to conquer neighbouring lands and persecute whoever didn’t follow the true Christian faith.

This set the scene for the supremacy of the Catholic Church, often through shear terror as we will see during the reign of Charlemagne and later on the Inquisition.

During the Concilium Germanicum (Council of Leptines in the Diocese of Cambrai) in 743 – at which Saint Boniface played an important role – a range of bans were introduced in which the secular (military) powers had to support the priests and bishops in the enforcement of them. They included bans against: animal and food offerings, offerings within dwellings, adoration of stones, rocks, springs and trees, making vows near thorn bushes, holy trees or springs, the cutting of wooden idols, or the making of images of devils, fortune-telling and predictions based of offerings of lots and so on. Rain and cloud incantations were equally forbidden as was sorcery, predictions made at the birth of a new baby, wearing and using of amulets. Pagan feasts were abandoned in particular those at new years eve and those on Thursdays (in honour of Donar). Having meals in churches , the singing of secular songs and performance of girl choirs were all off limits. If priests were involved in fortune-telling they were dismissed and put into as monastery.

By destructing famous temples of Zeus, Serapis and many others as well as of Holy Oaks and other holy pagan sites they showed the supremacy of their God.

The Church also put a lot of effort in breaking tribal structures, in order to get more power over the people, the Church had to take over the community culture. They insisted on using Roman Law on land ownership, this meant on personal title, until that time all lands – outside Roman control – were held within the tribal community. Families were ‘forced’ to enroll sons into the monastic system, whereby it was essential that they would break all ties with their families. The very first churches were built by the nobles (read former tribal chiefs) on their own lands and became more or less private chapels, for them and their (tribal) family. From the 7th century onward the Church rapidly started to built churches with the rural communities where they had an independent control over the local people. People were also ordered to bury their dead in the churches and the churchyards and it became forbidden to bury them in the traditional ways on their ancestral lands close to their living relatives.

These churches and in particular churchyards became the new areas for the community to congregate and they became the communication centres for the community, by doing so they further increasing the control of the Church over the people,

This militant aspect of this faith also allowed for a unified political system that started to evolve in Europe, especially under Charlemagne in the late 8th century. He adopted the concept of ‘temple destruction’ and under his regime missionaries such as Willibrord and Boniface destructed the pagan temples of the Germanic tribes. The Teutonic Order maintained that practice along the Baltic to well into the 13th century.

At the Council of Nicaea the Church official took over the Roman administrative system. Emperor Constantine organised the Council along the lines of the Roman Senate. It was also from this event that Church Councils became the institutions where creeds and canons were approved or disapproved, a tradition that has continues ever since. The word canon comes from the Greek word for reed; this was used by them as a measure stick. The Canon therefore is a measure, guideline.

The Church inherited and copied the late Roman imperial, legal and administrative structures (from Emperor Diocletian) based on the ‘civil dioceses’, these were tax collecting districts. Each diocese had a vicarius (vicar). The Emperor also appointed ‘duces’ they were commanders of the boarder troops, in later times dukes were people with authority over an important region.

Soon after Christianity had become the state religion in the Roman Empire, the Church started to align itself with the secular powers and adopted the secular Roman hierarchic structures also in its own structures. They argued that the secular structure had to be a mirror of the heavenly structure and therefore closely supported the monarchy as the best form of secular power.

Collapse of the Roman Empire

The collapse of the Roman Empire also undermined the unity of the Church as popes lost their vital communication with their bishops and abbots. The Church fell back to a range of localised activities. There had been just enough time for a church structure to arrive mainly around the bishops who were seated in the provinces/dioceses as they had been set up by Emperor Dioclesius. Already before the collapse of the Empire, there was an ongoing battle taking place among these early leaders to organise a universal church. The jockeying for power and influence took mainly pace among the bishops themselves, the pope had very little power as this point in time. However, the metropolitan bishops did get the upper-hand, they became the senior bishop over other bishops who operated in the provinces.

There were five main centres of Catholicism: Antioch, Jerusalem, Constantinople, Alexandria and Rome. While Rome was the most important one in the church hierarchy and the only seat with a number of provinces under it, the main centre of christian gravity remained in the east. There was ongoing rivalry in the east between Antioch, claiming to be the oldest, Alexandria which had been the most important see and the most homogeneous one. However with the dual role of the Emperor in state and ecclesiastic affairs it came as no surprise that Constantinople rapidly won the battle. The Patriarch of Antioch was the first to lose its independence when his appointment was now made in Constantinople. Unlike Alexandria however, the other sees (and in particular Constantinople) had to deal with a variety of Christian subgroups, which all had their own political influence and therefore had to be taken serious. Furthermore the Council of Nicaea had ruled that the local churches had great autonomy within their regions, add to this the political situation in Constantinople and its clear that it was impossible to create a uniform orthodox Christianity.

During the 4th and 5th centuries, very little development happened in the western part of Christendom.

After the fall of Rome, the imperial city further declined and the popes became isolated in Rome where they were often under siege of the local feudal rulers, the powerful senatorial families and the counts in Italy. For centuries they had very little authority outside Rome itself.

Building on the tradition that stared during the Late Roman Empire it were often sons of senatorial families, kings and other nobles who were made bishop and there were subsequently many prince-bishoprics, and many of them had very little interest in their religious responsibilities. With a mainly rural population, it were the monasteries that maintained the Christian faith during this period. The early missionaries and their monasteries are covered in a separate section.

The bishop governed the diocese with the assistance of his cathedral clergy (chapter) and especially from his archdeacon, his principal collaborator. The word episcopate is from Greek/Roman origin (epi-scopus) and means ‘over-seer’. Bishops were people with ambitions, they were rich, had significant properties and in general were large land owners, they often also had lots of enemies.

It was this Roman administrative heritage that kept the Church together after the fall of the Roman Empire. The Catholic institutions were often the only structures of governance that survived the collapse of the Roman Empire and by default they started to fill that vacuum. From this time onward the Church started to perform both secular and religious activities. However, as these two structures started to intertwine, the secular aspects started to become more and more important as that created power and wealth and these increasingly also the secular oriented rulers claimed that they equally had religious rights. Religion provided for stability and unity. In order to be part of the elite or to make promotion you had to be a Christian. By the year 1.000 what is now the Netherlands could also be called a Christian region.

The appointment of church officials, while theoretically a task of the Church, was in practice often performed by secular authorities. Since a substantial amount of wealth and land was usually associated with the office of bishop or abbot, the sale of Church offices (a practice known as simony) – while officially forbidden by the Church – was an important source of income for secular leaders; and since bishops and abbots were themselves usually part of the secular governments, due to their literate administrative resources, it was beneficial for a secular ruler to appoint (or sell the office to) someone who would be loyal. In the end these church rulers had very little to do with matters of faith, they fought wars, had wives and mistresses and often suppressed their object.

During the Roman Empire Gaul had become an important region with 18 provinces, the seat of power sat in Trier and from here the Church in Gaul was ruled. However, towards the end of the 4th century the Barbarian raids and insertions had made the region unstable and around 395 the Roman Praetorian Perfect was moved from Trier to that at stage little known town of Arles, also the seat of the Church of Gaul moved to Arles. Coming from nowhere Arles shoot up in military and administrative importance within a very short period of time. In relation to the Church this caused a severe conflict with the bishop of Marseilles who until that time was the leading church authority in southern Gaul. The issue came to a head at the Synod of Turin in 398 where the diocese was split in two.

Barbarian rules controlled by supernatural powers

As we saw in the section on the Prehistory, the migration tribes all followed the pagan religion. Travelling south during the 4th and 5th centuries, they however, were confronted with a new religion that especially over the years proceeding the initial invasion had swept through Europe.

Once these tribes moved beyond their own rather isolated pagan tribal structures, they were confronted with different structures from other tribes, this of course happened during the migration period. This confrontation led to confusion and a breakdown of their own world view. The super structure of the Roman Empire and Christianity provided that bigger world view and as such was rather rapidly accepted by the various tribal conglomerations (Franks, Goths, Visigoths).

Conversions happened within the heterodynamic model of the society – there was no individual decision making process. When the ruler was baptised the whole tribe was than basically seen as Christians. In order to maintain the support of the tribal chief their political structures were kept in tact, followed up by slow process of further infiltration of church rules and regulations. Later on a more military conversation was used.

Thanks to that rather rapid conversion the Church could wield that spiritual power and keep society together. This didn’t happen in England, where Roman society totally collapsed because the Angles and the Saxons had no concept of either the Roman society not Christianity. This happened there much later.

Most tribal leaders acquired the Christian faith from the early missionaries and took it on next to their pagan/Roman believes and traditions. It was relatively unimportant if their subjects actively followed this faith and in many regions it took many centuries for the populous to be truly converted.

Many of the pagan religious elements were simply Christened, through the uses of Saints these elements could also be localised. This made the transition from pagan to catholic much easier and also allowed for many Roman and pagan traditions to continue into this day and age. Perhaps the most famous is the birthday of the sun ‘Sol Invictus’ on the 25th of December. The Sunday – as the name says it – was dedicated to the Sun by Emperor Constantine in 321, this also became the sacred day in Christianity. Most of the superstitious believes were carried forwards into the new religion, however this time it was given a name ‘God’ and that stopped any further investigation of the nature of these superstitions.

After the collapse of the Roman Empire there was no longer central control. To counterbalance the lack of civil central authority, the Church used its supernatural powers to claim that authority. Basically (as Gregory of Tours indicated) ‘ don’t mess with the bishops otherwise this spiritual power will be used against you’. The bishops faced the barbarian and violent new rulers and they had to make sure that Church property was not used as targets in their raids and plunder tours. Miracles were used to implant fear in order to stop these rulers from attacking their (rich) possessions. While this didn’t always work, most of the time it did. The Saints – which provided an easy continuation of the many pagan deities – were especially seen as powerful and all the towns, churches and communities rather quickly had their own patron saints and through these saints the bishops had very strong powers over these local communities and properties , especially if relics could be produced to show these links with the saints; the more relics the more powerful these saints and very few (converted) barbarian ruler dared to mess with these powers; again miracle stories further emphasised these powers.

At the same time between the 5th and 9th centuries we see missionaries travelling through Europe, often with the support of the local nobility who had taken on the Christian faith. With their assistance they founded monasteries and on the lands of the nobility – the Merovingians and Carolingians – the first private churches started to be built (Eigenkirche). They also became the burial places for these people. During these period the monasteries were closed communities with little or no pastoral activities, if anything they would have been seen as economic powers by the local people because of their large scale agriculture and related activities. It was much later from the 9th century onward that parish churches started to emerge in greater numbers.

Pros and cons of Christian powers

As always and everywhere, power corrupts and also within this Church structure we see a widespread misuse of power and material greed; which bore little or no relation with the religious values that had formed the basis of these new structures.

At the same time within the Christian concept, bishops extended their powers over the poor and the weak and were able to also stop the usual violent attacks against these people, either as a result of raids or conflicts between the various fractions within the ruling class. The poor and the weak were in these days basically everybody not belonging to the ruling classes – anybody without power. Through the Church these people fell directly under the protection of God and especially also the Saints (local heroes, celebrities based on their miracle powers), at the same time the reality of that protection (again often told in miracles) created a loyal following of the Church within these communities. The Church also ruled that good deeds for the poor cancelled out some of the bad deeds that violent rulers conducted and as such the poor did have some power. In particular when disaster (within the ruling families) happened good deeds were done to obtain the good will of God and the Saints to divert disasters or deliver a victory, good fortune, etc.

Popes and bishops also greatly contributed to civic infrastructure developments such as water and drainage as well as in the beautification of Rome and later similar developments took also place in other Episcopal cities.

For well over a millennium the Nicaea structure was maintained, but the popes had very little authority over this process, often sons of kings and other nobles were made bishop they involved in secular prince-bishoprics. In the early days bishops could be married and in some places the position even became (semi) hereditary. There was a very profitable trade in the buying and selling the rights to run clerical offices (simony).

An important development took place in 554 when Emperor Justinian recaptured most of the western part of the old Roman Empire. He issued a Pragmatic Sanction, a far reaching piece of legislation that covered the repossession of Ostrogoth property, the restoration of the handing out of free grain to citizens of Rome, agriculture prices, excise taxes and research grants. Interestingly for Rome he also declared that its governors from now should be nominated by local bishops and all property previous owned by the Arian Catholic Church was granted to the Orthodox Catholics.

From this day onward Rome would no longer be the city of Caesars but the city of Popes.

Powerful multinational

From a religious point of view, the bishops were the spiritual successors of the 12 apostles. Paul appointed the two first bishops Timothy in Ephesus and Titus in Crete.

The churches in the region of a diocese were served by presbyters and deacons (and deaconesses). This structure was adopted from the organisation of the Jewish synagogues.

Canons, deans and deacons

A canon is a community of regular clergy who live according to certain rules (canones). They didn’t do their monastic vows. A canon consisted of 15 people: 10 priest and 5 deacons and sub-deacons. The head of the canon is the dean, often an important person of nobility. The dean was frequently also an archdeacon within a diocese. For this he had to be appointed by the pope.

Archdeacons could appoint and dismiss priests and chaplains. The parishes where therefore managed from the canonry. The powerful dioceses of Utrecht often appointed canons or munsters/minsters and members of these communities often ended up later on as parish priests. The properties and rights (tithes) belonging to a parish were often also inheritable (and tradeable) goods. Deans, deacons, counts, bishops and kings all played their political power-games within this realm.

Parish priests didn’t necessarily live in their parishes, they simply collected the income and appointed somebody to look after their affairs in the parish. These ‘priests’ often were illiterate themselves and had a lifestyle not much above that of the local farmers.

The Church was also the first organisation to introduce the concept of conferences. Hundreds of synods or councils have been conducted by the Church over the centuries. There were regional, national and international (ecumenical councils – oikoumenè meaning the whole of the civilised world). Some addressed very trivial issues, simply to confirm some donations or immunities and some were pure political. However, this (limited) democratic system certainly assisted in establishing internal cohesion.

In general it can also be concluded that Christianity became more than a religion, as secular and religious merged Christianity also became the way of life in Western Europe and eventually beyond Europe. So even those born and bred within those societies who are not religious can’t escape being part of the ‘Christian tradition’.

Bishoprics

Initially bishops were appointed to the new Christian communities that were rapidly establishing itself throughout the Roman Empire. Those bishops who moved outside the limes (Roman boarder) did so at their own request.

| Diocese | Established | First bishop |

|---|---|---|

| Trier | 50 | Eucherius |

| Mainz | 80 | Crescens |

| Cologne (Colonia Agrippina) | 88 | Maternus |

| Marseille | 1st century | |

| Lyon | 177 | Pothinus |

| Tours | 249 | Gatianus |

| Reims | 250 | Sixtus |

| Rouen | 250 | Nicaisius |

| Metz | 280 | Clement |

| Montpellier | 3rd century | |

| Paris (Lutetia) | 3rd century | Denis –died 250 |

| Bourges | 3rd century | Ursinus of Bourges |

| Bordeaux | 314 | Orientalis |

| Tongeren/Lièges | 344 | Servatius |

| Maastricht | 350 | Servatius |

| Besancon | 445 | Celidonius |

| Dijon | 5th century (or earlier) | Urbanus? |

| Arras-Atrecht/Cambrai-Kamerijk | 540 | Vaast |

| Utrecht | 695 | Willibrord |

| Freising (Munchen) | 739 | Corbinian/Boniface |

| Wurzburg | 743 | Burchard |

| Paderborn | 799 | Founded by Pope Leo III |

| Hamburg | 849 | Ansgar |

In the north-western region that we concentrate on the three important bishoprics between the Maas and Rhine during Roman times were Trier, Cologne and Tongeren. Also indicating the possible different tribal countries that these seats represented.

Church father Ambrose of Milan was born in Trier around 339, it had a strong Christian community. His sister Marcellina consecrated her virginity to God here in 353. The exiled Athanasius of Alexandria lived here from 335 till 337.

In the 5th century, during the migration period, there was a retreat of Christianity and many bishoprics were without their ‘Sheppard’ for many decades. This situation remained largely unchanged for the next 500 hundred years.

Under the Merovingians and Carolingians the situation did see a few improvements in favour of the Church. After the last effective Merovingian king, Dagobert, several bishop seized the opportunity to establish powerful bishop states, especially in the southern part of Goal, but also the bishop of Trier was able to rise in power. However in most of the northern realm of the Merovingian Empire, close cooperation between the rulers and the bishops, prevented the bishops from taking too much secular power. During the following period the number of political murders of bishops increased quite dramatically, amongst others Lambertus the bishop of Maastricht in 706

By 814, there were 21 archbishoprics within the boundaries of the Carolingian empire: Rome, Ravenna, Milan, Cividale, Grado, Cologne, Mainz, Salzburg, Trier, Sens, Besançon, Lyon, Rouen, Reims, Arles, Vienne, Moûtiers-Tarentaise, Embrun, Bordeaux, Tours and Bourges.

However, many bishops and abbots – during this period – were lay people appointed by the kings in exchange for financial or military favours.

The medieval bishoprics in the Low Countries

The developments of the bishoprics or dioceses in what is now the Netherlands dates back to Roman but mainly to Merovingian and Carolingian times. The first bishopric was that of Tongeren and was founded around 280. Legend has it that it was moved to Maastricht by St Servatius in 384 – historic evidence from 535 confirms Maastricht as a bishopric – from here it was moved in 722 to Luik (Liège).

The bishopric remained the name of Diocese of Tongeren. It extended from France near Chimay, to Stavelot, Aachen, Gladbach, and Venlo, and from the banks of the Semois as far as Ekeren, near Antwerp, to the middle of the Isle of Tholen in Zeeland and beyond the Moerdijk in Holland, it included both Romanic and Germanic populations.

The Diocese of Utrecht was established in 695 when Saint Willibrord was consecrated bishop of the Frisians at Rome by Pope Sergius I. With the consent of the Frankish ruler, Pippin of Herstal, he settled in an old Roman fort in Utrecht. After Willibrord’s death the diocese suffered greatly from the incursions of the Frisians and later of the Vikings. Willibrord was most probably instated as archbishop, having received the pallium during his life; but it is uncertain why and when exactly this title was lost in later times. Its territory included current Holland, Zeeland, Utrecht and most of north east Netherlands.

The eastern border of the Bishopric of Utrecht was shared with those of Münster and Osnabrück.

Most of Groningen and parts of Frisia as well as much of eastern Gelre (Gelderland and Overijssel) including Hengelo, Grol (Groenlo), Borculo-Lichtenvoorde and Bredevoort fell under Münster.

Westerwolde in Groningen was part of Osnabrück.

Nijmegen – as an imperial city – came directly under the Archbishopric of Cologne.

All of the above bishoprics were part of the Archbishopric of Cologne.

In the south there was an equally complex situation. Apart from Luik there were the French speaking bishoprics of Cambrai, Arras and Tournai. They all fell under the Archbishopric of Reims.

Around 540, St. Remi (Remigius), Archbishop of Reims established the bishopric of Arras but soon its See moved to Cambrai. Its territory included among others Brussels and Antwerp. In 1094 the bishopric was split in two Arras (Atrecht) and Cambrai.

Probably around 639, Saint Audomar (Saint Omer) established the bishopric of Terwaan or Terenburg in Thérouanne. It controlled a large part of the left bank of the river Scheldt. Territorially it was part of the county of Artois which originally belonged to the county of Flanders. In 1553 Charles V besieged Thérouanne, in revenge for a defeat by the French at Metz. After he captured the city he ordered it to be razed to the ground. In 1557, as a result of the war damage to its see, the diocese was abolished.

Legend has it that Remigius also erected the See of Tournai (Doornik) and its territory roughly equals that of the Province of Hainault.

Over the centuries the boundaries of these dioceses started to become very different from the secular boundaries, whom they mostly matched as they were at the time of foundation. This started to become an annoyance to the Burgundian and Hapsburg rulers, who had been pondering changes since Charles the Bold; not because of ecclesiastical problems but because of political and secular interests. However, there was always strong opposition of the various nobles who held rights in relation to ecclesiastic offices, properties and privileges; many of them neglecting or abusing those rights. On the other-side the populations often hated these ecclesiastic rulers and their often opulent ways of life – most bishops – and senior clergy in general – had totally alienated themselves from their people which greatly fuelled the spread of Protestantism in the region. What also played a key role in all of this was that in the See of Utrecht there were over one thousand parishes, especially those in the eastern part of the bishopric received little support and the management of these parishes was in general very poor [x. The Dutch Republic, Jonathan I.Israel, 1995, p 74-78].

When Emperor Charles V united the Burgundian Netherlands in 1543, he did find himself in the strange position that his northern procession largely fell under ecclesiastic jurisdiction of a minor vassal, the Archbishop-elector of Cologne and parts of his southern possessions fell under the Archbishop of Reims a vassal of his arch-rival the King of France.

It finally was his son King Philip II of Spain who in 1559 – fuelled by the rapid increase of Protestantism – forced through the reorganisation of the bishoprics. For this he received the support of Pope Paul IV who issued the Papal Bull “Super Universas” that made it all legitimate. He established 11 new dioceses; this brought the number of Dutch speaking dioceses from 2 to 11, covering some 3 million people. The French speaking territories were put under Cambrai which was elevated to an Archbishopric. For the southern Netherlands a new Archbishoprics that of Mechelen was established.

However, this didn’t last long as the bishoprics of ‘s-Hertogenbosch, Roermond, Deventer, Groningen, Haarlem, Leeuwarden, Middelburg were abolished again during the following decades when the Dutch Republic took over the control of the northern Netherlands. The Catholic faith was forbidden. It was not until 1853 before that situation changed and the Dutch Catholic hierarchy was re-established.

- Until 1559 the Parish of Oss was part of the Deaconate of Cuijk, Bishopric Liège, Archbishopric Cologne. Ootmarsum fell under Archbishopric Utrecht and Wietmarschen and Nordhorn under Bishopric Munster, Archbishopric Cologne.

Establishing Christian doctrine

The definition of what the catholic religion actually entailed and its rules and regulations was also a hotly debated issue during the first few centuries and it was only over time that the Christian canons were developed. Canons are a group of texts considered authoritative by the Church; they included the Old and New Testament, the letters (epistles) from Paul and the interpretation and organisation of them in canon law by the so called church fathers of which perhaps the most important one was Augustine. However it wasn’t until the 6th and 7th century before a more complete and clearer picture started to emerge of the christian doctrine. A key role here played Chrodegang of Metz. His Rules for Canons, fostered a quasi-monastic regime of communal life among the urban clergy, his rule was implemented in virtual all bishoprics.

Chrodegang of Metz

He was born in the old Roman civitas of Tongeren, of a noble Hesbay/Frankish family that via his mother Landrada was related to the Robertians, a Frankish predecessor family of what became the Capetians.

He was educated at the court of his cousin Charles Martel, became his private secretary, then chancellor, and in 737 prime minister. On 1 March, 742, he was appointed Bishop of Metz, while still retaining his civil office.

In 748 he founded Gorze Abbey (near Metz). In 753 he was sent to Pope Stephen II to obtain his support for the crowning of Pippin as the new Frankish king, who had disposed of the Merovingian King Childeric III.

Stephen turned to Pippin to in turn get his support against his fight with Aistulf, King of the Lombards, who were making inroads into the Papal Lands. Chrodegang accompanied the pope to Paris who on January 6, 754, personally consecrated Pippin as king.

After the death of St. Boniface, Pope Stephen conferred the pallium on to Chrodegang thus making him an archbishop, but not elevating the See of Metz.

Rule of Chrodegang

In his diocese ( and indeed in Gaul) he was the first to introduced the Roman Liturgy and chant (Gregorian), community life for the clergy of his cathedral, and wrote a special rule for them, the Regula Canonicorum, later known as Rule of Chrodegang. We saw a copy of the early documents in the Court D’Or in Metz, the former Merovingian palace and now museum. The rule containing thirty-four chapters which he gave his clergy (circa 755) was modeled according to the rules of St. Benedict and of the Canons of the Lateran. Through these rules he gave a mighty impulse to the spread of community life among the secular clergy.

Gregorian music

Pope Gregory the Great (590-604) has been instrumental in the musical liturgy. He established guidelines for the various forms of music for the different elements of the Holy Mass. He also founded the papal singing school ‘ scola cantorum’. His liturgy spread throughout the Christian world and is since 850 known as the Gregorian Liturgy.

Metz remained an important centre for church music and under the reign of Charlemagne, when his son Drogo was Bishop of Metz, further teachings took place here under the leadership of a monk send to the cathedral of Metz by Pope Leo. His teachings spread throughout the lands of the Franks and became known as Metx chant. In German Metz is pronounced as Mettis and the chant became known as the Mette.

He died at Metz and was buried in Gorze Abbey and died at Metz, March 6, 766. We visited his shrine in Metz Cathedral in 2009. The Cathedral also hosts the beautifully carved marble throne of Saint Clements, the founder of the cathedral. The throne has been the bishop’s throne since Merovingian times. In the treasury there is also the golden ring of St Arnoul, bishop of Metz and an ancestor of Charlemagne from 614 to 629.

The close relation between state and religion made it also easier to forcefully introduce and execute these religious laws. Charles the Great introduced a death penalty on pagans who didn’t want to be baptised.

The powerful axis between emperor and pope, together with the tight organisation of bishoprics strengthened the success of Christianity. At the same time the religion was also successful in attracting wealth, through a clever scheme linked to above mentioned promise of obtaining salvation after death as well as to its appeal to human ethics.

A very important consideration when looking at the Middle Ages is to imagine that there was no longer a distinction between Christianity and people in general. Christianity was not just a religion, it had become the custom of the land. Life was Christianity and Christianity was the only way of life. This was even extended to the animal world, as creatures created by God they were also seen as part of the Church and there are many occasions where animals are officially excommunicated, especially those creating pests and havoc such as caterpillars, mice and rats.

Perhaps by looking at some of fundamental theocracies in the Middle East is it possible to imagine what that society looked like.

The missionary urge became a key element in the expansion of the Church. The foundation for it can be found in the Gospels. Here, Christ told his 12 disciples to go out and preach the Christian message to the world. However it was not until, after the persecution period – at the beginning of the 4th century – before this missionary work got underway in any serious way.

While there are many negative aspects to the catholic conquest at the same time this also became the major driver behind healthcare, education and the many aspects of social work, all very critical elements in establishing a stable society. The western society would not have evolved without the Christian culture, tradition and religion.

Developments of calendars

With Easter such an important date in the Christian Calendar lots of effort was directed to making the calculations for the right dates. These calculations resulted in tables that than were used to fill in other important dates for the Church calendar. Increasingly the monks and scribes started to use the open table to record other developments, events such as storms and the arrival of comets and other activities. The Liber Pontificalis was another important developments in record keeping as it provided an overview of the popes together with important developments. The major prayer book of the Middle Ages, the Book of Hours, always starts with calender and the appropriate time for certain prayers are guided through this calender.

While the hierarchical foundation of the Church was built on the Roman structures, it failed to built the same cohesion. Papal authority was often very low and popes, bishops and priest were often involved in activities that were contrary to the vows that they had taken. This cumulated in the so called Papal Pornocracy. It finally was Pope Gregory VII who ended this situation, which led to the so called Gregorian Reforms. This led to the reintroduction of religious discipline, the fight against heresy and the reconquest of lost christian territories.

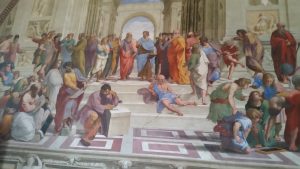

The end of reason

Both the secular and the religious powers very rapidly understood the value of combining their activities. The powerful state/religion alliance started to mold the new west-European society. Interestingly, until around 800, Greek philosophy – which had developed separately from mythology and religion and was based on observations in the natural environment – became a key driver behind the early Christian religious movements and Aristotle, while being a pagan, was seen as ‘one of us’ especially among the early church fathers. The Greek legacy could only endure because of the early medieval intellect was involved in a permanent dialogue with the knowledge of the great Greek philosophers. From now on philosophy and religion merged and once secular and religious powers started to join forces, dialogue, tolerance and reason where the first virtues that went out of the window. Reason was replaced by the precondition that any form of intellectual pursuit had to be based on grace and faith and on the the authority of the Bible and the dogmas of the Church – the dead-hand of religion.

After nearly 1,000 years Emperor Justinian closed the famous Academy of Athens – founded by Plato – as part of his imperial ban against pagan education. This clearly indicated that secular knowledge was no longer seen as a usefulness element to the development of the human being. Its most illustrious teachers where recruited by the Persian Emperor Khusro and recreated the academy at the Sassanid Capital of Ctesiphon, where the works of Plato and his successors translated into Persian and as such they were kept for humanity.

Sport had already been an earlier victim of the change. There is no consensus on when the Ancient Olympic Games officially ended, the most common-held date is 393 AD, when the emperor Theodosius I declared that all pagan cults and practices be eliminated. Another date cited is 426 AD, when his successor Theodosius II ordered the destruction of all Greek temples. This ended a tradition that had lasted for over a thousand years (since approx. 776BC). Organised sport didn’t return until the 19th century.

Fortunately some of the other legacies of the Classics were preserved, but many only just.Interestingly it was Charlemagne who has been instrumental in preserving some of the great classical works from Virgil, Horace, Pliny, Livy and Seneca for prosperity by employing hundreds of monks to copy these works in the various monasteries that he and his family had established. To show the impact; there are some 1,800 surviving manuscripts from between the years 0 to 800. From the following 100 years, 7,000 manuscripts survived.

It is also important to mention here – in the context of reason – that the men who copied these works, were simple copiers, very few actually did understand these works. This is totally different from the original writers and their students they very actively discussed and debated the issues written down in these works. The Christian scholars simply wanted to use these works to support their own view on life.

By 750 the tolerance from the previous centuries had been replaced by doctrine and the philosophy of reason was replaced by the doctrine of faith. Nothing could be challenged anymore and science came more or less to a total standstill. All cultural, art and scientific developments for the next four centuries took place within the Church (monasteries, churches, cathedrals and cathedral schools) .

Those who challenged the new society rapidly were expelled as heretics and not following the faith meant ostracism. Over the next millennium millions of people around the globe were killed under this regime. Many remnants of that rather intolerant culture are still lingering on in our society.

In the absence of science, people assumed that there was direct divine intervention in all aspects of their life. This view was held not just by peasants but also by the nobility and the intelligentsia of the time. Because of the lack of reason every single aspect of life was seen as an Act of God, very rarely were causes and effects questioned let alone researched. Bad weather, natural and other disasters, illness, disability, racial and cultural differences were all seen as punishment of God. This was not limited to people, the wrath of God also affected animals. The level of indifference is sometimes hard to understand. Survival was what pushed people forwards, following a more or less ‘animal-like’ instinct. A very biological rather than intellectual response. There was little pity for the unlucky ones or those who were ‘different’. Apart from survival, faith ruled the life of the people of the Middle Ages, that’s what kept them going during famine, epidemics, natural disasters, war and basically in all aspects of life. Yes they could die any time, but there was the unquestioned belief in the afterlife and the real fear of hell. This overarching set of beliefs became the self perpetuated prophecy of the Middle Ages.

It is interesting to note that all of these people involved in shaping Christianity throughout the ages based their activities on their interpretation of the Bible. This led to very bad behaviour in the case of the persecution of Jews and anybody else who didn’t follow the doctrines of the Church to the letter, the wholesale slaughter of ‘pagans’ be it in medieval Europe or later on in South America. On the other side we see the positive social developments, looking after the poor, the sick, orphans, etc. The schooling and the works of people like Saint Francis.

These developments are dealt with in more detail in: The infallible medieval believe system

The History of Northwestern Europe (TOC)

[1] Beryl Smalley; Historians in the Middle Ages 1974, p63