On 11 February 1842, Moreton Bay was officially declared open for free settlement. The 2nd and 3rd offending convicts – for which the penal settlement was established – were send back to Sydney. Instead 55 ‘ordinary prisoners of the Crown’ were send to Brisbane to assist in setting up the free settlement. Twenty two were assigned to the surveyors – see below – three were employed at the hospital, one to the pilot crew at Amity Point, four as boat crew for the settlement, the rest were assigned were needed.

While transportation to NSW was officially stopped in 1840, it continued to other parts of the colonies. The majority of British convicts were now increasingly put on hulks on the Thames,. Interestingly however, during the 1840s, convict ships from Britain continued to be diverted from Sydney. In 1849 a change in government in Britain led to yet another overturn in policy. As a result, a convict transport was sent directly from Britain to Moreton Bay, but the change in policy proved to be short lived. With transportation to all of the eastern colonies drawing to a close, the last direct shipment for Moreton Bay left Britain in April, 1850.

After the 1853 penal servitude act, only long-term transportation was retained and it was finally abolished after the penal servitude act of 1857. Some convicts were still transported for a while after the 1857 act. The last transportations took place in 1868. However, there are no records indicating that convicts still arrived in Brisbane after 1850.

However. all of this uncertainty meant that the future of Brisbane remained in doubt. As during convict time their was ongoing indecisiveness from the authorities in London, yes or no penal settlement, yes or no transportation, yes or no to Brisbane. At that time there also was still the option to close the settlement all together, or direct new settlers to other places e.g Ipswich. Lack of communication between London, Sydney and Brisbane was another major obstacle and it could sometimes take two years before an answer was received. In the meantime Brisbane muddled on and most likely because of that it survived. The main reason was that the fertile lands of the Darling Downs and the Brisbane River started to produce significant amounts of wool. The squatters here were not going back any time soon and while they squabbled over where the capital of Moreton Bay should be, Ipswich, Brisbane or the sea port at Cleveland , Brisbane started to become an important centre for the squatters. Nevertheless the uncertainty often led to tension between the two communities. When the squatters (mainly their workers) came to town this often led to drunkenness and brawls. At the same the Squattocracy tried to establish some exclusivity, which was most obvious at horse races, initially they wanted to keep this exclusive to themselves. This continued over the next one and a half century. They made sure they dominated the early Sate Parliament wherever they could – later through the Country Party – and this only ended after the Bjelke Petersen era.

As this was the only place with significant government buildings, it was natural that North Brisbane had the potential to become the administration and service centre for the region. Nevertheless without any government plans the people remained divided and rumours of what the government’s (un)decision would be continued during this period of uncertainty. People were worried on where to invest, how much money to spend on maintenance and equally for the squatters uncertainty regarding their leases was frustrating.

In relation to the convict buildings a plan was developed in 1839. All buildings except those for military purposes should be transferred to the colonial government in Sydney. Again plans were delayed because of indecisiveness in London, but finally implemented in 1842.

During the convict era Brisbane had become the centre of a large government pastoral empire. In 1839 the government owned close to 1000 cattle and over 4,500 sheep.Cotton suggested the sale of these herds. In 1842 a start was made with the sale but was not completed until 1848. The slow decision making processes saw the government missing the boom time and it was forced to sell during an economic depression.

Finally after more than 30 years, certainty arrived as the Municipality of Brisbane was gazetted on 25 May 1859 as proclaimed by the Governor of New South Wales and the official papers arrived in Brisbane on 7 September 1859. Because of the delay in communication between England and Queensland the official papers for the separation of Queensland from NSW took longer to arrive so the Queensland Proclamation took place in December that year, after the Brisbane Town was already officially established.

For the time being the town’s main raison d’etre remained a service and shipping centre for the pastoral and agriculture developments that were taking place to the north. Mining was added later. It wasn’t until the 1880s before Brisbane in its own right started to develop into a city.

While in the 1840s several bank agencies became available it was not until 1850 that the first local bank opened; the Bank of NSW had just beat the Bank of Australasia, other financial services followed soon after that.

The arrivals of the surveyors

In 1839, in preparation for the opening of the settlement, six surveyors including Robert Dixon, James Warner, Henry Wade and Granville Slapylton were sent from Sydney to draw maps of the district and prepare town plans so the land could be put up for sale. However, with ongoing uncertainty about the government’s plan for Brisbane and the larger Moreton Bay area, this was often a start and stop process, with a lot of indecisiveness in between.

Eventually the proposed street plan was for square blocks of 10 chains (200 m). It also included a range of gardens: the military gardens and Dixon’s garden behind the Military Barracks; Whyte’s garden to the northwest of the Prisoners Barracks, through which Burnett Lane now runs; Reverend Handt’s garden and Kent’s garden to the rear of the Chaplain’s house and Commandant’s house; the Commandant’s garden; and Paget’s garden and Dr Ballard’s garden adjacent to the Hospital.

There was again disagreement as visiting NSW Governor George Gipps was still opposed to the free settlement being built at the riverside. Others suggested Cleveland Point to him. On arrival in March 1842 he was totally bogged down in the mud at Cleveland Point, so that plan got rapidly abandoned., only to resurface again a year later. The issue simply would not go away as long as there were the opposing interest between those in the city and the landowners in the country. Other suggestions for a permanent settlement other than Brisbane included Maryborough (settled in 1847) a port at the Mary River further north. The death nail for Cleveland came in that same year when it was decided to build the Customs House in North Brisbane. Captain Own Stanley reported that Cleveland Point is not at all adapted for a shipping port.

Back in Brisbane Gipps was not happy with plans of the surveyors. He thought that the roads were to wide, that he thought the reserves to be a waste of land and that the allotments were too small. He wanted the plans to be changed but he received opposition from the Superintendent of Works Andrew Petrie. Gipps wanted the streets to be not wider than sixty feet however, Petrie didn’t want to give in and in the end he agreed to 80 feet.

They also started to survey roads as was earlier proposed by Commander Cotton. In 1839 Dixon surveyed the rod to Cowpers Plains and Eagle Farm. The following year Stapylton surveyed the road to Limestone.

Dixon and Commander Gorman didn’t go on together very well which led to the dismissal of Dixon. While Dixon was an excellent surveyor he was not a town planner. Surveyor Henry Wade modernised Dixon’s plan in order for it to be more relevant to town planning . He developed the CBD street grid as it still exists and developed rectangular city blocks that were suited for businesses and housing (rather than for farming). he also imagined in his plans the parks that later became the City Botanic Gardens and Roma Street Parkland. Following an official complaint against him, Wade was laid off in 1844 and left Brisbane two years later.

In July 1842 the first land auctions, totalling 13½ acres, were advertised and comprised of the block bounded by Queen, George, Elizabeth, and Albert streets – and a section in South Brisbane. The auctions were held in Sydney. There was significant interest from the people here and the land was sold well above the reserve price. However, this was mainly because of Sydney investors, who never intended to settle in Brisbane and or build a business here. The first auction delivered over £ 4600 to the government, well above expectation. However, several of the investors later sold their land at a loss. With an economic downturn in 1843 following land sales were much less successful, it was not until 1846 before the market recovered and economic activity started to recover. This was also not helped with a total lack of interest from the government to spend any money on maintenance, infrastructure and utilities. They also cut the salaries of the surveyors in half and many of them struggled to and do the surveying work and maintain a family.The only stretch of ‘made’ road so far had been the mile along the government’s wharf. It was a matter of self-help for the settlers to repair bridges and keep tracks passable as much as possible.

The very first house in South Brisbane, a weatherboard one, was built later in 1842 by David Buntin in Grey Street. A wool store and of course an inn followed soon after that.

The town plan allowed the subdivision of allotments to the river’s edge. The first ones in North Brisbane, South Brisbane and Kangaroo Point. A private ferry linked the North and South Brisbane from 1842 onward. By that time the town had just under a thousand inhabitants. The second ferry crossing between North Brisbane and Kangaroo Point was leased to a private contractor two years later. A road from the ferry (Main Road) led straight to Ipswich Road and provided the wharves in Kangaroo Point (like South Brisbane) with direct access to the Darling Downs, at this stage that road was not much more than a dray track.

They also surveyed the lands beyond the townships and on one of these expeditions Stapylton was killed by Aboriginals.

Back in 1825, Commandant Henry Miller of the penal settlement had selected the triangle of land bounded on two sides by the Brisbane River and the escarpment which is now Wickham Terrace. At the survey of the town in 1839 surveyors marked the city boundary to the north and west along what is now Boundary Street in Spring Hill., Vulture Street on the south and Wellington Road on the east. In 1846 the Police Act of 1839 was applied to Brisbane which allowed Police Magistrate John Wickham to remove and prevent nuisance and obstacles within these boundaries as well as a better alignment of the streets.

Over time a fence was built from what is now North Quay over Spring Hill (Boundary Street) to Petrie’s Bight. This boundary was revised in 1856, expanding it from Petrie Bight (Eagle Terrace) out to Boundary Street (now Boomerang Street in Milton. Boundary Creek marked the extension of the city’s new boundary.

In 1859 August Gregory was appointed as Queensland’s first Surveyor General.

The arrival of the first settlers

The first settlers that arrived came on their own, either attracted by business and land opportunities or as squatters. These are people who occupied a large tract of Crown land in order to graze livestock. Initially often having no legal rights to the land, they gained its usage by being the first settlers in the area. They in particular went into the fertile area of the Darling Downs. Also Brisbane had become an official immigration outlet, it was there to serve the bush. People should not settle in Brisbane but were send to the squatters who were in desperate need of labour. In those early days the Brisbanites were not looking for more shop and factory competition in town, while the squatters could never have enough shepherds. There was no demand for female workers so the population remained very lopsided. In 1846 there were 614 male and 346 female inhabitants. That year a call went out for female servants, who arrived earlier in that year, by the end of that year most were married.

There was a large influx of Irish immigrants and this led to a significant increase in Catholic infrastructure such as schools, orphanages and convents throughout Brisbane. In 1855 1,000 Germans arrived from Hanover and in 1868 554 Danes. During this period another 1,00 Chinese cooks, shepherds and farmhands were deployed mainly in the Darling Downs.

Already in the early 1840s pastoral products started to arrive in Brisbane from these squatters, before this town was officially declared open for free settlers. They were rapidly followed by business people supplying the various services for the squatters as well as town services such as pubs, labourers, wharfies, prostitutes, etc. This added to the frontiers atmosphere of those early years.

By 1844 there was still only one general store, though other commercial business included two milkmen, a sawyer, a butcher and a blacksmith. There were also two hotels in Queen Street, Bow’s (Victoria Hotel) an the Sovereign Hotel and as could be expected of a frontier town, Brisbane society was predominantly masculine. Law and order was both rough and very public, with floggings being conducted in the main thoroughfare of Queen Street until 1847; hangings continued as a public spectacle in Queen Street until 1855.

In the 1840s, there was a scattering of dwellings on the edge of Brisbane in Spring Hill, Fortitude Valley, Petrie Terrace, South Brisbane, Kangaroo Point and Woolloongabba. Apart from the buildings from the convict era the new buildings from the settlers and immigrants were not more than slab huts. A decade later dense bushland was cleared and the settlement spread further to Yeronga, Bulimba, Moggill, Indooroopilly, Enoggera, Milton and Toowong. The convict buildings were now used for many decades for public activities (courts, police, government clerks, land office, and in the 1860s even to house the first parliament). By 1861 the settlement had just over 6,000 inhabitants.

The service function continued and by the mid 1850s businesses started to spread beyond Queen Street, Edward, George and Adelaide Street now also saw =businesses starting up. There was no planning involved and it was a tangled mess of shops, sheds and cottages, with government buildings in between. Along the river more wharves and stores were build and the most significant industrial development at that time was the opening of the steam saw mill of Fortitude immigrant William Pettigrew in 1853 on North Quay. A brewery and sift drink manufacturing plant followed suit. John Williams who operated a small scale coal min in Mogill opened a distribution depot next to the Victoria Wharf. A range of agents acting on behalf of companies in Sydney and London, settled in town as well. In 1851 no less than 15 new liquor licences were handed out for hotels across the sprawling town. New boarding houses followed. It remained a boom and bust cycle with regular business collapses especially during economic downturns. Initially when some gold was discovers around Brisbane, in the mid 1850, business was boomerang.

However, when more serious amounts of gold were discovered in Gympie in 1867, large numbers of Brisbanites tried to find their luck on the goldfields and it was reported that one in five houses in Brisbane stood empty.

The roads were not much more than tracks, nearly impassable after rain. Flooding was a reoccurring event especially of the low laying parts of the settlement. Overcrowding and lack of hygiene were major issues in the first few decades of the period of free-settlement. The healthcare system remained appalling as it was in convict times. Most newcomers had little resilience against the tropical diseases. Infant mortality stood at 50%. Fresh water supply remained a problem, again as it had been in convict times. The so called fresh water reservoir at Roma Street was now known as ‘the hole of death’. Water was also carted from Breakfast Creek and One Mile Swamp in Woolloongabba. The latter also became totally unusable for drinking water as cattle and horse freely used the swamp. In 1851 it was reported that it was no more than a ‘thick yellow puddle’. Two years later some improvement occurred when openings were made in Russell Street for the laying of drainage pipes.

In 1852 the government provided £150 for the deepening of the reservoir at North Brisbane (Roma Street) also a fence was built to stop cattle venturing into the reservoir.

It was not until 1866 before a more sustainable solution was established through a pipeline from the newly created Enoggera Dam. This became the first reticulated gravity supply of water to the city and the first municipal engineering undertaking in Queensland. It included the building of two tunnels one of 170 meters and one of 350 meters long. The water was pumped into the Spring Hill Reservoirs.

The constant uncertainty about the future of the settlement, the indecisiveness of the Governments in Brisbane and England and a total neglect of infrastructure, only fueled the call from independence. Dr Lang (see below) was one of the first to call for separation from NSW and during the 1850s the groundswell grew larger and larger.

Religion, education and healthcare

The problems with spiritual service to the community continued in its poor state, While towards the end of the convict period German Evangelical Lutheran Missionary Reverend Johann Christian Simon Handt had made some good progress. After the close of the penal colony he successfully applied for the use of chapel in the room over the entrance arch of the convict barracks. However, as a result of his limited achievements he was send back to Sydney in 1843. His replacement the Anglican Reverend John Gregor was equally unsuccessful and received a motion of no confidence from the parishioners in 1846.

If it wasn’t for the Scottish Presbyterian Reverend Dr John Dunmore Lang things would have continued that way. He arrived in December 1845 and started two daily church service in the chapel of the barracks mainly for the Presbyterian communities in North and South Brisbane and Kangaroo Point. However, of the 1000 inhabitants only 10% belonged to this congregation.

While the Church of England made up close to 50% of the population, including the more wealthier ones, the congregation failed to raise funds for a church. They were using an old convict barn in the former lumberyard for their services. This barn held 150 people but only had a few windows. Finally in 1854, they were the last of the mainstream denominations to acquire their own church.

The lack of spiritual interest also reflected poorly on education. Schooling was a church organised activities, but the Bishop of Australia only wanted to provide £25 annually for education, the rest needed to be funded by the parishioners. Churches and private enterprise stepped in and several people started to offer day and evening classes both for children and adults in a range of education branches. An Anglican, Wesleyan and a Catholic school were started. However private education remained the main form of education. The thirst for knowledge also saw private initiatives to start a library and a reading room. The thirst for information was quelled with the arrival of the Moreton Bay Courier in 1846. Schools also started to pop up in Kangaroo Point.

The success of private education initiatives also led, in 1849, to establishing a School of Arts, for the discussion of literacy, scientific and other subjects. Slowly also cultural and entertainment activities started to arrive, not always with the same level of success.

Sport became a more successful early activity. It started with horse racing, first within town, but soon racecourses started to be established. There were annual footraces, regattas and cricket had an early but not so successful start. Bathhouses along the river also started to arrive.

The free settlement was lucky that Dr. David Barlow the surgeon of the convict settlement stayed on. He had an assistant, Peter Nichols and furthermore three convict were allocated to the hospital. The hospital situated between George Street and North Quay was thus able to remain operational. The Colonial Government wanted to see the convict hospital closed (and stop funding it) in 1843, but reprieve was given as an epidemic was raging at that time. Governor Gipps was able to delay the closure and ultimately able to covert it into a colonial hospital. However in 1848 the government stopped all healthcare funding. As Brisbanites had learned to look after themselves rather than depending on government assistance, they had established the Benevolent Society. This provided the members with some ‘users pay’ healthcare insurance and also provided some money to look after those who couldn’t look after themselves. They raised enough money to take over the running of the hospital. Fortunately the government agreed to hand over the buildings, the beds and all medical instruments to the Society.

The first dentist arrived in 1852, when J.F. Charet, a watch and clock maker offered his services to stop decaying teeth without pain to the patient by the administration of the mineral succedaneum. However, he achieved real fame by discovering gold within a mile from town.

Reverend Dr John Dunmore Lang

Lang, with his enormous energy, passion and often unconventional ways of getting things done played a critical role not just in a spiritual sense but even more so in the early period of immigration. Lang was a conservative protestant with outspoken opinions on moral issues. This brought him in conflict with the more moderates within the Presbyterian Church. His abrasive personality and high-handed approach saw him twice ending in goal and resulted in numerous court cases and fines. To support his views on church issues, morality, independence and republicanism, transportation, slavery and numerous others issues he published magazines, pamphlets, books and letters to the editor. He travelled very regularly to Britain, also made a trip to America and visited Brazil.

He saw the damage done by the Industrial Revolution in England and thought that immigration could assist people to have a better life. He also was highly critical of the convict and transportation systems and saw them as undermining a moral society. After he visited Moreton Bay in 1845, he went back to England trying to gain support from the government to set up an Protestant emigration system to Australia (Moreton Bay and Philip Bay in Victoria). However, his readiness to challenge the civil authorities was not well received. He was an avid supporter of republicanism and even wrote the “Declaration if Independence’ for the Colony of Victoria in 1853. He actively lobbying for Australia to become an independent nation and the Governments in London and NSW were not a bit interested to make that happen. He also wanted Cooksland (his name for what is now Queensland) to become independent from NSW

He charted ships to bring the first privately sponsored immigrants from England arrived in two batches. In late 1848 the British Government brought in 240 settlers and looked after them on their arrival. A month later the more than a 1,000 Presbyterians sponsored by Lang arrived. On arrival of the three ships chartered by him, the Fortitude, Chasely and Lima the (NSW) government officials in Brisbane refused any assistance to settle these newcomers. Lang had never completed such transactions with the Government.

Immigrants paid Lang for a block of promised land through his Cooksland Colonization Company. The immigrants however, saw all of Lang’s promises disappearing in hot air. Lang had to scramble to provide accommodation and food for the newcomers. Police Magistrate John Wickham (see below) took pity on these new arrivals and arranged they could put up tents and build slab huts. They spread out over the town, concentrating in Bulimba, Petrie’s Bight and Bell Valley. The current name of the latter is Fortitude Valley, renamed after one of the three ship these immigrants arrived on (Fortitude, Chasely and Lima). John Wickham knew well that the free settlements needed lots of workers and most indeed did receive work after their turbulent arrival. However, most of them held a lifelong grudge against Lang.

For example, one of the immigrants, George Dickens had paid Lang £100 for 80 acres which he never received (Sharyn Merkely writes about this in her book Brisbane Burns). Lang ended up in financial problems as these emigration schemes were costing him large amounts of money. However at the same time many immigrants were grateful for his assistance and friendship. Because of the shortage of labour most immigrants rather quickly did find either work or employment.

The squatters on the Darling Downs kept lobbying the government for convict labour and in 1850 the ship the Bangalore arrived with 292 convicts and 104 free men. women and children. The latter included 29 former military men who also became permanent settlers. The arrival of new convicts was not without controversy as the people in Brisbane were largely oppose and abolition meetings were held. Despite ongoing lobbying the Bangalore was the last formal convict transportation from England to Brisbane.

For many years to come attracting new settlers to Brisbane/Queensland remained one of the most serious problems of the colony.

Urban sprawling

Some of the earliest land purchases around Brisbane were made in the area just north of the main settlement area in what is now Spring Hill. In the early days the area between Spring Hill and Fortitude Valley was known by the somewhat oxymoron name of Valley Hill and remained covered in virgin forest. After butcher George Edmonstone had removed his sheep from Windmill Hill, Spring Hillbecame the most desirable residential area in Brisbane, and the Edmonstones were among the first to move there. Early subdivision of the area in the 1850s saw the gazetting of Wickham Terrace (see below) and Gregory Terrace.

Fortitude Valley was popular among immigrants and by the early 1850s it had become the largest suburb and hosted (of course) a pub and a police man.

In 1842, Pendergast, a farmer from Wollombi in the Hunter Valley planted maize at New Farm and weeks later the crop stood nine feet high. He was perhaps the first farmer from the ‘north’ that settled in Brisbane. In the 1850s cotton and arrow wood were successfully grown and exported, as well tropical fruits such as pineapples. Food supply however, remained in short supply and the flats along the river with its fertile soil attracted farmers and this is how during the 1850s and 1860s New Farm, Eagle Farm and New Farm developed.

Gregory Terrace was named after Queensland’s first Surveyor-General, Augustus C. Gregory and was the northern perimeter of Brisbane Town from 1859.

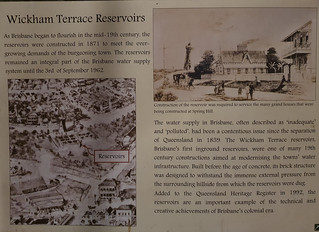

The Spring Hill area had rapidly become the exclusive part of town and was one of the first areas to have a reliable water supply in Brisbane, first from the natural spring that gave its name to the suburb and then in the 1870s from the reservoirs built behind the windmill on Wickham Terrace.

They were built in two stages between 1871 and 1882, these were service reservoirs designed to assist the Enoggera Dam and improve water pressure to the central business district. It continued in this role until 3 September 1962, when increasing high-rise construction, together with the reservoirs’ small capacity and low elevation rendered it unable to serve the city’s requirements. In recent years, the reservoirs were opened to the public as a cultural event space, best known for hosting the productions of the Underground Opera Company.

The new settlers did want to forget the origin of the settlement as soon as possible and rapidly the name Moreton Bay was replaced by Brisbane Town, for a while however, both names continued but eventual Moreton Bay started to refer to the district. This lingered on till independence in 1859, when Queen Victoria personally insisted that the name for the new colony had to be Queensland.

Population statistics vary across sources but they followed roughly the following growth pattern At its height the penal colony had a population of around 1200 people, around 90% being male. In 1847 the population stood at close to 1500 people, now approx. a third were women.

The census of 1851 provides a further break down. The population now stood at 2097 in North and South Brisbane and Kangaroo Point, a further 446 lived in the ‘suburbs’. There were 1480 males, of which 870 single and 1063 women. There were still 50 convicts in the settlement. Religious breakdown: Anglicans 965, Roman Catholics 707, Wesleyans 261, Presbyterians 187 and other protestants 268. Labour statistics: skilled artisans 247, other labourers 205, farmers 233 (of which 195 lived in central Brisbane).

At independence in 1859 there were 7000 people and 5 years later the population stood at approx. 12,500. By this time there were three village, North Brisbane (around the original settlement), South Brisbane and Kangaroo Point Village (together these last two village had a population of approx 350 people at that time). The 1864 census recorded 2456 buildings in Brisbane, of which 16% were of brick or stone.

Further north Ipswich had been growing significantly challenging North Brisbane as the most important settlement in the most northern part what still was NSW and also the Darling Downs (Drayton, now part of Toowoomba) had become a prominent settlement. During the convict era river transport took place by row boats. Such a trip would take around 12 hours from Brisbane to Ipswich. Punts and rafts flowing with the tide would take several days. In 1846 the first paddle steamer steamer service started to operate from Brisbane to Ipswich along the Brisbane and Bremer rivers. A steamer followed the following year. But such a boat trip could take six to seven hours. The first railway arrived in 1864 between the Darling Downs and Ipswich. Squatters actively prevented to extend the railway to Brisbane as they continued to prefer Ipswich as their major service centre. The railway was finally extended to Roma Street in Brisbane in 1874. In the end this became a great transport improvement for all .

South Brisbane and Kangaroo Point

The river was a big divide and South Brisbane had much better access for ships coming from Ipswich. In the early years it had more buildings than North Brisbane (83 to 75), but half of North Brisbane’s were stone while all but one on the other side were timber. It rapidly developed itself as a frontiers town (with all the relevant ‘entertainment’ and crime attached to it).

South Bank, close Kangaroo Point, saw the first primitive wharfs, basically logs place next to the river bank. Where they were tied to the ‘famous’ Macintyre Gum Tree. After a dispute with owner, the Hunter River Steam Navigation Company built, in 1845, close to that spot a river wharf and stores. A few years later they moved their wharf to North Brisbane. Over the following decade more wharves were built from Petrie’s Reach to Town Reach. By 1850 it had five ship wharves.

Kangaroo Point had an early advantage over South Brisbane as had its own wharf

The first ship built in Brisbane, the cargo schooner Selina, was at the wharf in Kangaroo Point in 1847. It was launched at Petrie’s s Bight opposite of where the Howard Smith Wharf is now. It first trip was to deliver timber to Sydney. However, the ship never reached its destination. A year later it was found at what is called Wreck Point near Rockhampton, without crew, waterlogged and the mast cut out, but with its cargo intact, a total mystery.

South Brisbane was basically a service centre with stores, pubs, brothels and workshops used by the people coming and going to Ipswich and the Darling Downs. There was a big social divide between South Brisbane and North Brisbane, the South being the poorer part, house prices here were a fraction of those on the other side of the river. Kangaroo Point was rapidly evolving in an industrial hub. It started with the boiling-down plans for the squatters in the Darling Downs by 1848 this smelly plant was moved to Ipswich. By that time related industry such as soap and candle making and leather works had also established here. In 1847 a woolshed was opened. A bank agency and several retail outlets started to operate from here. Boat building also arrived around this time.

The big divide between South Brisbane on one side and North Brisbane on the other side started to change when a bridge was built, but also this was not as simple as it should have been as we will see below.

The latter area, well known for its good pastoral land saw the arrival of squatters already from around 1840 and the land grab could hardly be managed by the NSW Government. By 1854 all the land here had been sold.

Frog’s Hollow

A special mentioning here is needed for Frog’s Hollow. This was the area directly linked to the centre of the old settlement and the emerging CBD. It basically was the precinct enclosed by Elizabeth, Alice, George and Edward Street. In the centre was a tidal swampy depression and a creak running through the area. The area already flooded at a high spring tide, so imagine the situation at the regular real floods. No wonder that the site was well known for the nightly loud concerts of frogs.

On the 14th January 1841, the settlement was largely flooded as the river reached a maximum level of 8.43m at the gauge, it is the highest flood level recorded to date. This reminded of a description from historian Margaret Cook: A River with a City Problem.

In 1851 the authorities agreed that the swamp should be drained and that flood gates should be installed on the creek leading to the river to avoid back-washing.

Frog’s Hollow was the most disreputable area of Brisbane. Over the decades following the convict era it became occupied by legal and illegal pubs, brothels and gambling places. One of the most notorious gambling dens was on the corner of Elizabeth and Albert Street. Frog’s Hollow also housed a range of workshops and stores as well as the Red Light District. The majority of police arrests took place in this part of the town.

Perhaps the most infamous part within this already seedy part of the town was a row of nine shops, known as ‘Nine Holes’ situated between Charlotte and Margaret Street. These narrow dwellings had a shop room in the front and a sort of cellar room behind it and were occupied by Chinese immigrants. They were the most run down and unsanitary lodgings in town. While this area was also known as the Chinese Quarter there were only a relative very few Chinese living in this part of town.

If we talk about the floods of Brisbane than this part was always the centre of the disaster. The area attracted the poorest of the poorest and as their numbers grew, the area became more and more densely populated and over the years the floods caused more and more misery and damage.

A start without money

Before the State of Queensland was established in 1859, most proceeds from land sales, taxes and (gold) mining royalties went to NSW. There was hardly any money for public works or public buildings anywhere in Brisbane, let alone in the poorer areas. It was often left to the early settlers to get money together for fixing the roads as well as for looking after the social needs of new immigrants.

The handful of better to do settlers became the defacto rulers of the settlement. The divide between them and the ordinary people was great. They looked after their own interest and had little regard for the rest of the population. Furthermore, there was a lot of infighting between the rulers as they foremost wanted to secure their individual interest.

This hampered the development of a more civil society. There was no regard for the rights of the Aboriginal people and many were killed by the settlers. Crime was high as poverty stricken people roamed – often drunk – the street. With an unbalanced gender population prostitution was high, there were many brothels and it were often Aboriginal women who where abused, often for the lure of alcohol (rum).

In 1827, the first Chief Constable appointed to – the at that stage still convict settlements – was ex convict John McIntosh. His task was basically to try and capture escaped convicts, often tracking on foot along the Queensland Coast. In late 1833 he was followed by another ex convict, Richard Bottington. The first non-convict police officer, William Whyte, was appointed Chief Constable in 1836. The Police Act of 1838 provided for appointment of police magistrates and justices to suppress riots, tumults, and affrays in towns. In 1840, the police force of Brisbane Town consisted of one Chief Constable William Whyte; a bush constable and four convicts employed as assistant constables. Most of the early policemen were ex soldiers. There was at the time no police training or police manual so trained soldiers was the next best option.

The Military

The Moreton Bay area and beyond started to see large numbers of new settlers. As the squatters extended their properties and more started to arrive, the Aboriginal people were pushed of their lands. They obviously didn’t take this laying down and significant armed resistance took place, especially between 1842 and 1844. In 1842 the last Commander had left Brisbane and while the official authority was situated in Sydney, the area was basically left on its own. Most squatters were magistrates and therefore had a certain level of legal authority. They requested military assistance from NSW to fight against the Aboriginal population. During the 1840s the number of soldiers increased from 20 to 50 and at its peak close to 100, in all some 600 British military were deployed during these years.

Detachments included the 99th (Lanarkshire) Regiment 1842-48 (with the 99th also forming the military force at the short-lived North Australia Colony in 1847, the site of which later became Gladstone); 58th (Rutlandshire) Regiment 1844-45; 11th (North Devonshire) Regiment 1849-50; and 12th (East Suffolk) Regiment 1860-66.

Some of the new recruits were deployed at the Mounted Police. With no longer a Military Commander in place officers became local magistrates. Being military men they saw their role in fighting a war with the Aboriginal people and never intervened on their behalf when their land was taken away by the squatters.

In September 1843, at the battle of One Tree Hill between Mount Tabletop and Mount Davidson (near Toowoomba), the local Aboriginal people supported by the Mountain Tribes and led by Jaggera headman ‘Old Moppy,’ and his son Multuggerah successful fought armed squatters and ambushed a dray transport. They won that battle which ended in a temporary peace arrangement. Shortly after that the 99th Regiment established a military fort at Helidon from where it escorted dray transport to and from the Darling Downs. Some attacks however, continued as late as the 1850s and 1860s.

The key officers in the wars with the Aboriginal people were Lieutenant Patrick Johnston from the 99th Regiment, who commanded the troops in 1842-43. Followed by Captain William Edward Grant from the 58th Regiment in 1844. Francis Robert Chester Master commanded the detachment of the 58th Regiment briefly between November 1844 and January 1845. He later sold his commission upon and bought Mangoola near Warwick.

Towards the end of the decade the armed rebellions were broken and in 1850 the last British soldiers left Brisbane to be replaced by a locally formed militia.

It were not only the Aboriginal people that suffered from the British Military. Be to a far lesser extend also people involved in internal colonial conflicts suffered. The Brisbane detachment of the 12th Regiment included a number of men who had served on the Ballarat Goldfields, including the storming of the Eureka Stockade on 3 December 1854, while others saw service during the two military expeditions to the troubled New South Wales Lambing Flat Goldfields during the anti-Chinese disturbances of 1861-62. Some soldiers served as part of one (or both) 12th Regiment detachments dispatched from Sydney. Brisbane’s 12th detachment was also called to arms during the threatened ‘Bread Riots’ in September 1866.

Pre-Governor John Wickham

A name very much linked to the period between 1842 (end of the convict settlement) and 1859 (independence of Queensland) is Captain John Clements Wickham. In 1843, after his retirement from the Royal Navy, Wickham was made Police Magistrate. Wickham was first officer on HMS Beagle during its second survey mission, 1831–1836. The young naturalist and geologist Charles Darwin travelled as an ‘extra’ on the ship.

After the last Commander of the penal settlement Owen Gorman had left, Andrew Petrie became some sort of a caretaker of the place. On his arrival Wickham was charged with looking after the general government interest and was the Representative of the NSW Governor. He had a handful of conscripted men as his assisting force. Wickham was generally well liked by the emerging free settlers community. By 1850 his team consisted of a district constable (the 2nd highest in command in the colony), a watch house keeper and nine constables.

Under his leadership – between the 1840s and 1850s – the free settlement of Moreton Bay saw further reforms, legal, governmental, social and policing. A Police Magistrate, Court of Petty Sessions opened in 1846, a new Police Force was organised in 1850. While changes to the act were made, the structure and the work of the police force in Brisbane remained more or less the same over the next few decades. The Convict Barracks were renovated in the 1850s, to serve as a court and later as a Supreme Court (and after separation as Queensland first Parliament).

By this time it became clear that Brisbane was now seen as the future capital of the new colony.

In 1853 Wickham was officially appointed Government Resident of the Moreton Bay District in the Colony of New South Wales. He had taken office in the old convict barracks and it was here that he also preceded over minor crimes, major ones had to be referred to Sydney. On Sundays the courtroom acted as a church. He resided at Newstead House, Brisbane. This became the place where the pinnacle of society met and got dined and wined.

Wickham Street was named after him as this was the bridle track he rode to the courtroom, and rode back at night along this route. Wickham Street is an extension of Queen Street all the way to Breakfast Creek in Newstead. Since that time four more streets have been named after him, as well as Wickham Terrace.

Wickham retired in 1859, when the Moreton Bay District was separated from NSW, forming basis of the Colony of Queensland. He left as the Queensland and NSW governments disagreed over who was responsible for his pension, Wickham moved to France, where he died.

German Mission at Nundah (1838-1848)

This was the first mission in what later became Queensland and its aim was to bring the Christian faith to the Aboriginal population.

The German mission ‘ Zion Hill’, was unusual in many ways. It was a combined Lutheran/Presbyterian/Pietist effort with Moravian inspiration. It had an unusually large number of staff for a Protestant mission – two ordained priests accompanied by ten laymen, eight spouses and 11 children. It received a annual $for$ grant from the Government. Despite is size it failed in its mission and the government stopped with its subsidy, the mission was slowly disbanded and ended in 1848.

However, it played a more successful role in facilitating the settlement of Moreton Bay. Some of the phlegmatic German missionaries stayed on and became pioneer farmers imprinting their names on the modern Brisbane map: Rode Road in Chermside and Wavell Heights, Zillman Water Holes, Zillmere, and Zillman Road in Hendra, Gerler Road in Hendra, Franz Road in Clayfield, Wagner Road in Clayfield, Nique Court at Redcliffe, Haussmann Courts and lanes in Meadowbrook (Loganlea) and Caboolture. They are remembered as the first free settlers of Queensland, producing the first free-born settler children in Queensland. They also became the main suppliers of fresh vegetables for the budding settlement on the river.

The mission also established its own school for the children and as such this became the first (not officially recognised) private school in the colony. The school also taught Aboriginal children, however, their attendance was sporadic and very irregular. The school teacher was Reverend Christopher Eipper and his assistance was the Reverends Schmidt.