Why do I talk about icons? As most of you might know I am interested in art and in particular the history of an artwork and an artist, seen in the context of historical events and timeline. I have studied a couple of years of art history at Sydney Uni, just for my own interest, no degree. And in 2015-2016 I followed an icon painting course given by Anita Strezova in Sydney and made a couple of icons using the traditional tempera method, which I will also use in my presentation.

I would like to start my talk from four phenomenology viewpoints:

Firstly: my interest in icons is personal;

Secondly: I do love the cultural and mystical aspect of them;

Thirdly: historically the development and location of the Byzantine empire in eastern Europe and Asia minor, and the schism in the catholic church in the 11th century (1054) that split the church into Western (Roman catholic) and Eastern (Orthodox) is an interesting part of history on many levels: theology wise, and cultural and art historical;

and last but not least, the symbolism in icons applies to many other forms of religious art such as the use of colours and gestures

So let me first explain some terms.

The word Icon comes from the Greek word eikṓn (PRONOUNCE IEKṓN)– meaning image, representation and covers not only painting, but also sculpture and even mental images. In the Art historical use of the word icon the word stands for a wood-panel painting of a sacred subject intended for adoration and meditation. By extension, the term is extended to sacred images in general, including wall paintings and or mosaics, but the size and mobility of painted wood panels gave icons a special place in medieval life.

Icons form a central part of Byzantine art. The term Byzantine commonly describes:

All art works created in the Eastern Roman Empire (Byzantine empire) from about 5th century until the fall of Constantinople in 1453, and after 1453 when it became the Ottoman empire.

The term has also been used for the art of states which were contemporary with the Byzantine empire (eg Russia, Bulgaria, former Yugoslavia, Greece, Albania, Romania and also Venice and Sicily which had close ties with the Byzantine empire).

Byzantine art grew from the art of Ancient Greece and never lost sight of its classical heritage but was distinguished from it in a number of ways. The most profound of these was that the humanist ethic of Ancient Greek art was replaced by a Christian ethic: if the purpose of Greek art was the glorification of man, the purpose of Byzantine art was the glorification of God, Christ, the saints and martyrs.

History

Writings, dating from the second century, already mention images of John the Apostle that were used for private devotion. However in the early times it were not only the Christian saints that were displayed. Also images of pagan gods were painted in tempera on board, or by the encaustic method, and worshipped in private houses. One such image was discovered in Egypt and dated from the around 200 ad. It was painted in tempera (egg based paint traditionally used for icons) on a light coat of gypsum on a wooden board held together by a frame.

Here you see on the left the pagan Egyptian water god Suchos, clutching the crocodile sacred to the Nile, and Isis, holding a sheaf of corn. Unfortunately, this icon was in the museum in Berlin and was destroyed during WWII. This icon had a sliding door, so the icon could be concealed.

Although these images show pagan gods, they are very different from the traditional classical paintings: the figures are static, facing the viewer. There is little attention given to their anatomy or their spatial setting. The halo around their head attracts the viewer’s attention and emphasises the power of the god. Christian icons show the same lay out and emphasis. The pagan Greek politician and philosopher Dio Chrysostom (around 100AD) stated that the gods have no human form and authentic face at all, but in the absence of their human form “they can be represented as human because the human form was the most godlike form on earth”. For Christians, however it was important that the face showed authenticity as Christ and the saints did have human bodies and recognisable facial details

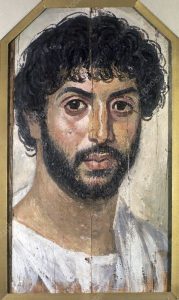

In contrast to the pagan tradition, where the body was fully shown, in the early Greek and Roman tradition of secular portrait painting, the emphasis was put on a head and shoulders portrait, and not on the whole body. The image of this beautiful Roman man dates from around 200 AD and is in the Pushkin museum of fine art in Moscow. Here the artist used the encaustic method to create this image by mixing hot wax with pigments. You can see on this image how the wax creates a translucency on the skin of the man.

So slowly the Byzantine icon tradition evolved mixing Roman portrait painting with imagery of Christian saints, Mary and Jesus.

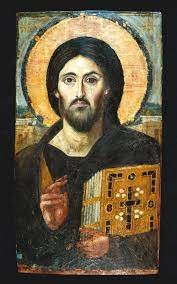

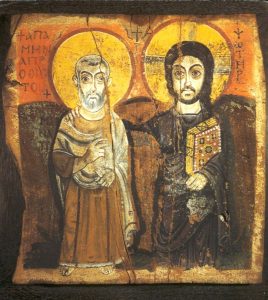

There are still Christian icons from the 6th century, and some can be found in the Monastery of St Catherine in Mt Sinai in Egypt (the oldest continuously inhabited monastery in the Christian world). But most portable icons are taken out of their ‘natural’ surrounds and are displayed in musea around the world. One of these sixth century icons is in the Louvre; depicting Christ and St Mena. A dark-haired Christ (depicted here as Christ philantropos = lover of men) has put his arm around the shoulders of Abbot Mena, as if to accompany him into paradise. Their feet are resting on the picture frame as if to step into the viewer’s world and the figures are set against the landscape, not in the landscape. Christ is holding the holy book while St Mena is giving the blessing. The face is not in proportion to the body as the face is the most important part.

We are lucky to still have these early medieval religious images as many have been lost during the iconoclasm period in Byzantium in the 7th and 8th centuries, when a few of the bishops in Asia Minor raised the problem of idol veneration prohibited in the Old Testament. Emperor Leo III in 726 took up this cause and here we have the start of an incredibly destructive period in art history: iconoclasm. In the following 150 years many discussions and propositions were held to come to an agreement between the anti and pro believers – the iconoclasts and the iconophiles – in the veneration of human forms in images and sculptures.

The iconoclasm’s point of view was that displaying icons is an evil practice of the devil, coming from a pagan tradition, and this tradition has brought the veneration of idols into the Catholic Church. The accusation of idolatry is also based upon the practice of venerating lifeless images as opposed to the living image of the soul of the saints. In addition to this theory, the iconoclasts laid their emphasis on what constitutes the nature of true worship. They argued that God is spirit, and those who worship Him must worship in spirit and truth, rather than worshipping Him through images made of matter.

The iconophiles’ argument was put forward by St John of Damascus from Syria. John was a polymath interested in the fields of law, theology, philosophy and music and declared a Doctor of the Church by the Catholic Church. St John who argued on the display of images of Christ: and I quote: “when he who is bodyless and without form, immeasurable in the boundlessness of his own nature, existing in the form of God, empties himself and is found in a body of flesh, then you may draw his image and show it to anyone willing to gaze upon it”. In this he stated that icons were the assertion of the full humanity of Christ, a doctrine very important for Byzantine religion.

And the second Council of Nicaea in 787 held by the Roman and Orthodox Church and supported by the empress Irene attempted to resolve the Iconoclastic Controversy, by stating: “the honour which is paid to the image passes on to that which the image represents, and he who does worship to that image does worship to the person represented on it.” However also this decree was not sufficient to stop the destruction and it was not until another iconophile empress, Theodora oversaw the final rehabilitation of icons (March 843). Her son re-instated the image of Christ even to the gold coinage.

The arguments on the veneration and the display of images in religious institutions did not stop here and continued for centuries.

The tradition of icon painting however expanded and in the 10th century we see icons in non-orthodox states such as Venice (which had close ties with the Byzantine empire) and the Kingdom of Sicily. With the fall of Constantinople in 1453 and the rule of the Muslim Ottoman empire, Byzantine traditions in icon painting survived. Called the post-Byzantine artistic tradition, it spread in the 15th century to Italy. In the late 19th century, with the decline of the Ottoman empire, the neo-Byzantine style developed. This style of byzantine painting can also be found in Australian orthodox churches, eg the St Catherine Greek orthodox church in Mascot. And I can recommend anyone to visit this church as it is a beautiful church and a very welcoming community.

This is in short an historical overview of the Byzantine icon tradition. I will now move on the symbolism in and philosophy behind the imagery and use of colours.

There is a clear difference between the West and the East in relation to the use of imagery. Orthodox iconography is a theological art, that means it expresses a theological vision, the truth of the Gospel, through colour and lines. Icons can give the viewer a transcendental experience, a guideline to the spiritual world. Icons were used for meditation and for contemplative reflection, so their imagery is very much abstract. They were not made to tell a story like many of the sacred paintings in Western art. This dichotomy already existed in the sixth century when pope Gregory instructed bishop Serenius, who had destroyed all images in his diocese after he found that the people were paying too much homage to them, to re-instate religious imagery in churches. Pope Gregory stated that: “paintings are books for those who do not know their letters, the illiterate, so that they can take the place of books, especially among pagans.” This concept of education through imagery was even included in the Libri Carolini from Charlemagne from the 8th century where it says that the Greeks places all their hope on the icons, whereas the Latins venerated the saints in their relics, in their ecclesiastical ornaments or in memory of past events

The early middle ages saw an increased use of icons in Christianity while other religions followed the aniconic worship: there were not representations in the Jewish religion after the sixth century; in Zoroastrianism fire became the sole iconic symbol; in early Buddhism – 1st century – Buddha was symbolized by an empty throne, or a Bodhi tree; the Islamic religion does not use physical representation.

Icon painting is a meditative, prayerful and somewhat ritualized art form, in which the materials and processes, as well as the image itself has symbolic meaning. God’s whole creation gathers to create the icon, from the board used, preferably oak or poplar, to the gesso (rabbit skin glue mixed with chalk), to the materials used in the painting technique and finishing layers (pigment, egg yolk, water).

The colours used in iconography all have meaning, one cannot choose any colour to depict the image. The iconography of icons is uncomplicated, easy to understand and uniform. As mentioned before, icons were used for meditation and for contemplative reflection, so their imagery is very much abstract. When we look at the facial features of an icon, we see the image of the person portrayed, without depicting his/her essence, the spiritual qualities. An image on an icon is to remind the viewer of the spiritual aspect of the depicted, not to depict the spiritual aspect.

This explains the abstraction used in icon imagery: the term ‘abstraction’ in this context is to be understood in its etymological sense as an act of ‘drawing out’ or retrieving something covered in order to reveal it. the painter removes all elements that would distract from the portraying of the image. Thus the painter makes the image more abstract, and this purified form is rendered in an artistic manner, appropriate to the sacred person’s image

When we look at icons and byzantine images in churches etc, the first thing that strikes is the use of gold, and bright colours. In their art, each colour had its place and value. Colours – whether bright or dark – were never mixed but always used pure. In Byzantium, colour was considered to have the same substance as words, indeed each colour had its own value and meaning.

As mentioned the use of colours, highlights and shadows is also strictly ‘regulated’…..

This is one of the icons I made when I did my icon painting course. Here you see two sorts of gold used: gold leaf and gold paint.

Gold, as a noble material, is used to abstractly represent the royal glory of the Divine. Similarly, a rich deep blue, used in Greek Byzantine art is used to represent glory, like the brilliant red preferred by certain Russian iconographic schools. The pigment blue is derived from a precious stone: lapis-lazuli that comes from Afghanistan; the colour red comes from cinnabar (a sulphite mineral). Lapis-lazuli and cinnabar are more or less equivalent to gold because they are noble, precious, and very expensive materials.

In traditional icon painting, red clay is used to create the red colour border: red clay symbolises the earth from which God created Adam.

The first layers of paint are dark olive or black, called Roshkrish, applied in round circular motion that will show as shadows throughout the painting process. These colours represent the ‘chaos’ or the primordial energy of the universe

Highlights within an icon represent Theocosm – the spiritual lights, and Anthropos – the enlivening and human intellect and culture, or if the highlights are done in small radiating lines, it is called Assiste and represents the divine energy and the uncreated light of God.

Deep shadows, such as we see in eg Caravaggio’s art by the use of chiaroscuro and sfumato are seldom used in icons. The reason for this is, and I quote from ‘The pictorial metaphysics of the Icon’

“(Because) the icon painter depicts the being of a real thing, the essential goodness of the being (Saint, or Mary or Jesus): a shadow on the other hand, is not being but the absence of being. Thus, to depict a shadow would be to characterise an absence by something positive, by a presence – and that would be a radical distortion of ontology.”

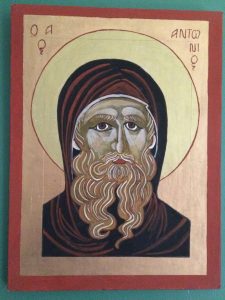

And with this deep philosophical quote, I would like to end my presentation looking into the eyes of St Anthony of Egypt, also called Anthony the Great who lived in the Egyptian desert around 300 AD. He is often referred to as the first monk (the Greek word for monk, monachos, means single, or solitary, applying to St Anthony who withdrew in the desert, fighting his shadows.

Louise Budde