The Old Batavia

Our visit to Jakarta began on what was once the Stadhuisplein of Batavia, today’s Fatahillah Square. This was the administrative heart of the VOC’s Asian empire, where decisions shaping global trade were once made. The former city hall still dominates the square, its solid 18th-century façade now housing the Jakarta History Museum. Around it stands the old Court of Justice and two merchant houses, while in front sits the cannon known as Si Jagur. Cast in Macau by the Portuguese, captured by the Dutch at Melaka in 1641, and brought to Batavia soon after, it remains a symbol of maritime conquest and control.

Just off the square runs the former Nieuwpoortstraat, once the main commercial artery linking the Stadhuisplein with the VOC’s imposing warehouses and offices. The street still reflects the symmetry and ambition of the early colonial city. Facing it is Café Batavia, the 1830s merchant house where we paused for lunch and later returned for dinner. With its shuttered windows, polished teak floors, and walls covered in colonial portraits, the café captures the layered history of Batavia better than any museum display. There is also an Australian link to this café.

The Amsterdam Canal and the Chines Massacre

A short walk north once led us to the Amsterdam Canal, which carried goods and traffic between the harbour and the inner city. During the Chinese Massacre of 1740, thousands of victims were thrown into its waters. We walked over the now filled canal, that once ran some distance away from the square; today, small houses and a narrow footpath trace its course through what is otherwise a quiet and poor residential area.

Weltevrede – Merdeka Square

From the old city, we followed the historical shift of Dutch power to Weltevreden, the new colonial centre developed in the early 19th century under Governor-General Herman Willem Daendels. Appointed in 1808, Daendels ordered the demolition of much of Kasteel Batavia in 1809, reusing its stones to construct new government buildings in Weltevreden. This became the fresh administrative and residential hub of the Dutch East Indies, situated on higher, healthier ground away from the coastal swamps. At the National Museum, originally part of this colonial quarter, we climbed to the rooftop for a broad view over Merdeka Square, once Koningsplein. From there, we saw the Merdeka Palace, formerly the residence of the Governor-General and now one of Indonesia’s official presidential palaces. The view extended beyond the historic core to modern Jakarta’s skyline — a forest of high-rises and glass towers showing the immense economic progress the country has made since colonial times. Today the city is home to around eleven million residents.

Tolerance in religion

On one edge of the square, the Jakarta Cathedral and the vast Istiqlal Mosque stand opposite each other, symbols of Indonesia’s religious and cultural harmony. The Gothic cathedral, completed in 1901, faces the 20.000 seat mosque, inaugurated in 1978, their shared proximity embodying the spirit of unity within diversity that defines modern Indonesia.

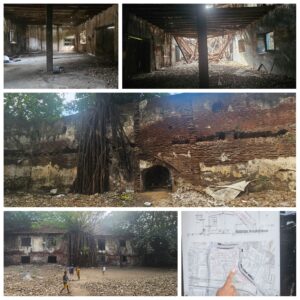

Kasteel Batavia

Later that day we explored the site of Kasteel Batavia, the old VOC fortress that once guarded the mouth of the Ciliwung River, known in colonial times as the Groote Rivier. Only fragments remain, but the outlines suggest the scale of the stronghold that served as both trading post and political centre of the Dutch East Indies. The fort’s Waterpoort once opened directly onto the river, connecting it to the harbour. Stones intended for this gate were aboard the VOC ship Batavia when it wrecked off Western Australia in 1629, linking two continents in one story of maritime ambition and loss.

Not far from the site stands the old wooden drawbridge, built around 1628, which once crossed the canal then known as the Groote Rivier — today the Kali Besar. Rebuilt in 1630, it remains the only surviving Dutch-era drawbridge in Indonesia and a rare piece of 17th-century engineering still spanning its original waterway.

The old harbour of Batavia

We ended the day at Sunda Kelapa Harbour, where wooden pinisi schooners still unload cargo by hand, as they have for centuries. The massive VOC warehouses and the nearby old fish market stand as sturdy survivors of Batavia’s seafaring legacy, their weathered walls echoing the city’s commercial past.

Buitenzorg

On our journey south toward Buitenzorg (Bogor), we stopped at the Dutch Field of Honour at Menteng Pulo, a cemetery containing about 4,300 graves of Dutch and KNIL soldiers and civilians who died during World War II and the Indonesian War of Independence. The white headstones and small chapel offer a quiet, sobering reminder of the shared sacrifices and complex ties between the Netherlands and Indonesia.

In Bogor we visited the Botanical Gardens, founded in 1817 by the German botanist Caspar Georg Carl Reinwardt while serving under the Dutch colonial administration. Surrounding the neoclassical Bogor Palace — once Buitenzorg Palace, now another one of Indonesia’s presidential residences — the gardens remain among

Asia’s most significant centres for tropical botany. Within the grounds lies a small Dutch cemetery, its moss-covered headstones dating back to the 18th and 19th centuries, a peaceful testament to those who once made their lives here.

From the remains of Kasteel Batavia to the tranquil gardens of Buitenzorg, our journey traced the evolution of Dutch influence in Java — from fortified port to colonial capital to mountain retreat — each stage leaving its mark on the landscape and memory of modern Indonesia.

Exploring Java’s Colonial Legacy: Bandung, Cimahi, Yogyakarta and Surabaya

The Moluccas: Islands of Spice, Memory and Continuity

Kapitan Pattimura (Thomas Matulessy) and the 1817 Maluku Uprising

The Long Road to Independence: From Colonial Resistance to the Birth of Indonesia