At (for us) unpredictable moments hunting parties were organised. The women went out looking for bush food while the men went hunting for kangaroos, etc. These hunting parties were highlights for both (white) men and women. It was on occasions like these that I got the feeling the Aboriginals as were treating us as their sons in a process of initiating.

We were told about the rights and duties of men, about family relations, how to prepare campsites, how to make cooking fires. Women were told about medicine, food preparation and a lot of things involved in running a family.

And then of course the Tjukurrpa stories. Driving through the land we were explained how the Ngintaka man (goanna man) created this part of the Musgrave Ranges and the land around Angatja. At certain spots specific songs were sung and dances were performed, and information was transferred to us in relation to the ceremonies.

The hunting itself was very exciting, cars and guns of course had their impact on the traditional way of hunting but the atmosphere surrounding this activity is still very much the same. Hunting is done for food not for the sake of killing. The hunt is also very much arranged by the kinship and Tjukurrpa traditions.

The Pitjantjatjara, in contrast to their South Eastern brothers, the Koori’s, have a so called positive totemism. This means that one can kill his own totem. In fact, killing and eating his own totem enhances the position of the person and will strengthen him. The Koori’s were not allowed to kill or eat their own totem which is called negative totemism.

The most important food for the Anangu is the ngin-taka (goanna) which is plentiful in these hot areas. The Ngintaka man is the most important Tjukurrpa hero-spirit for the Anangu. The hunting takes place under the leadership of the elders. They say where to go and they spot animal tracks even from a driving car which we would not have noticed even if we had stepped on them.

Before British invasion hunting was done within the family groups or individually. Man and wife would set up a camp, the man would go hunting while the woman stayed around. The hunter would not drink during the hunt (where we stayed, temperatures were up to 40°-45°). The Anangu were used to not drinking much water. This saved them carrying it all the way with them. When the hunters came back, they would still not drink water and were not allowed to talk to the women. They first had to prepare the game, once this was cooking in the ground-oven, they could drink. This was done because all day the game had been exposed to the heat and had to be cooked as quickly as possible. Nowadays, the Anangu still drink very little water in comparison with us, white people.

The campsite had of course a campfire. When it was cold, a large ditch was dug, hot ashes went into it, white sand on top of this and the Anangu slept in the ditches and covered themselves with sand. They had one and two persons “beds” and each person had a little night fire next to him/her.

With the four-wheel drive we went into the bush and on indication of Ilyatjari or Barney, two of the elders, we suddenly left the track and followed the foot of the hills where they expected the ngintaka near the rocks. We also looked for kangaroos and emus.

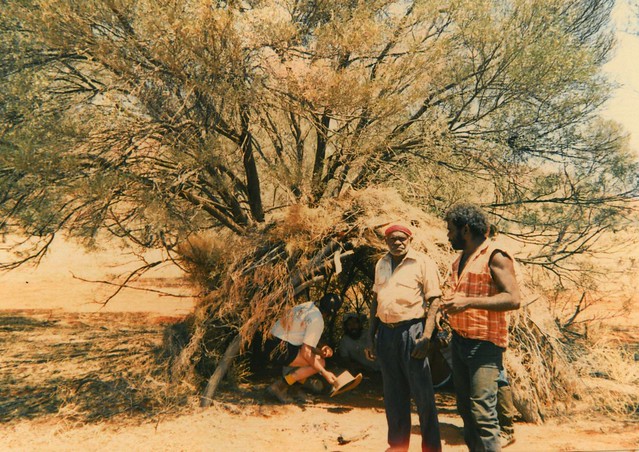

We crisscrossed the bush and at such occasions Ilyatjari told our driver to stop and asked us: “Where is Angatja?”. Generally, we indicated at least three different directions to him. The Anangu of course did not have any problem allocating themselves anywhere in the bush, the same applies for their children. During one of the hunting trips, we had “lunch” at a bush campfire. This place had a half round hut (wiltsja) made of mulga branches and covered with leaves. At this campsite, Ilyatjari prepared one of the ngintakas. This was done by making a little hole in its under-belly, thus allowing the guts to be taken out. He used sand to make it rough. Once the gall bladder passed the hole, the ngintaka was ready to go on the fire. Half an hour later, the animal was cooked and Ilyatjari distributed the meat amongst the hunters.

On another occasion, Barney indicated to the driver to stop. He got out of the car, ran into the bush and we heard a shot and another ngintaka was caught. This all happened while we blinked our eyes.

We also went to a salt lake. The wet shores always attract animals, in this case, especially emus. There were a few mulga bushes, an ideal spot to stay covered until the emu was within killing range. There were no emus this time but the area behind the mulga was littered with ‘rubbish’ – for hundreds of years it had been used by the Anangu who, while waiting for the emus, repaired or made spears, axes and other tools, the old stone spearheads, flint stones, and other materials that were no longer of any use were left behind. And as no (white) man has yet been there, it is all still there.

The next thing that happened was that one of us spotted a small red kangaroo. Immediately the excitement was there. We drove straight through the bush, narrowly missing trees, rocks, logs, etc. It was no easy task for our driver but miraculously we did not crash and finally we caught the animal. It was only then that we found out that the front window of the car showed a very large crack.

At the spot the guts were taken out, cleaned and re-used to tie the kangaroo’s legs and tail in such a way that the hunter could carry the animal on his head back to the camp site. Both Ilyatjari and Sammy showed us this tradition

In our case, the animal was put on the roof of the car and off we went again. Another kangaroo was traced and this time we caught it within ten minutes. It was still alive, and it was killed by hitting the animal in the neck. Both the hunters and the car were by now covered with blood and a very peculiar smell.

Back to the camp site. The hunt had been plentiful – so reason enough to sing an appropriate song: “The hunters are going back to the camp carrying the food” – an excellent song that was sung repeatedly. We also discussed that the Konga (women} would be proud of us when we would arrive with such a good catch. Back in the camp we were not allowed to talk or drink, first we had to cook the kangaroos. New lesson: this time we were shown how to break the legs, cut the tail off and how all of this should be placed on the fire.

Everybody shared in the food, but the hunters got the best parts: the top parts tails of the kangaroos were cut up between them.

Wirras and Honey Ants – collecting bush food