The first 20 months of the war we follow mainly based on Herman’s war archive.

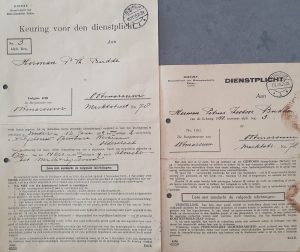

My father was conscripted during the mobilisation of the Dutch army in August 1939. He was called to travel to Hoorn in the province of North Holland. The mobilised troops arrived in Hoorn by train on 29 and 30 August 1939. During these days it was impossible for normal citizens to travel by train as all the trains were overloaded.

To be able to shelter the soldiers who were deployed in Hoorn, all kinds of provisions had to be made. Hoorn became the home for the 8th and 19th Battalion of the IV Infantry.

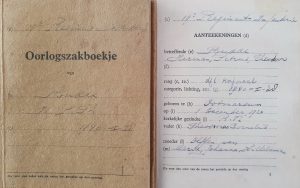

Schools and other institutions were commandeered to cater for the military influx. Herman was a corporal in the 19th Infantry Regiment and was posted in the ‘Krententuin’ a former labor colony on Oostereiland, a small island in the Ijsselmeer just opposite the city of Hoorn.

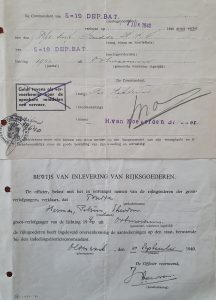

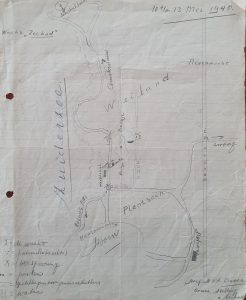

When the Germans conquered the Netherlands in May 1940, he – as a 19-year-old – was put in charge with the defensive position “Zeebad” (next to the harbour). The maps he created for that purpose are still in his archive. However, with the rapid defeat of the Netherlands, only a month later his regiment was disbanded, but not before all the soldiers had thrown their weapons into the the harbour of Hoorn to prevent them from falling into the hands of the enemy. He went back to Ootmarsum, where he soon became involved in the resistance.

After the Germans invaded the Netherlands, it would be almost two years before my mother started her diary. This is characteristic of the first 12 to 18 months of occupation.

The general thought was, on the one hand, that things would not be so bad. The occupier promised that everything would stay the same and that the Netherlands would remain independent. Adaptation and fidelity to authority was characteristic of the first year of the war, this often blind awe for leaders and the neat discipline also arose from the silo system described in appendix 1. The Dutch civil administration was one of the best of all occupied counties, the identity card almost impossible to forge. All set up by dutiful Dutch civil servants. This made it very easy for the Germans in the following years to round-up all the Jewish people in the country.

Others thought that economically it could not be much worse than under the Government of Prime Minister Colijn and were willing to give the new order a chance.

Only a very small part of the population was immediately aware of the seriousness of the matter and an even smaller part, less than a few thousand, was actively engaged in resistance.

More than in other countries, the Dutch responded to an increasingly more detailed series of bureaucratic assignments from the occupier. In countries such as France, Spain and Russia, the resistance started immediately. In the Netherlands, everything was neatly inventoried at the request of the occupying forces, food, bicycles, radios, non-Jewish declarations were signed by the tens of thousands. The occupiers had rapid access to a huge amount of information. It only became clear to the Dutch at the end of 1941 and especially in 1942 what all this law-abidingly meant. But by then, half the land had already been plundered.

The most dramatic thing was that the Dutch bureaucracy, together with the initial law-abiding nature of the population, contributed to the fact that the Netherlands, after Poland, has the largest number of Jewish victims. While in the Netherlands 75% of all Jews died, in Denmark it was only 2%, in Belgium 40%, in France 25% and even in fascist Italy ‘only’ 16%. The Netherlands was not an anti-Semitic country, but there was widespread passive Antisemitism. The Dutch government in London and Queen Wilhelmina rarely paid attention to the Jewish mass murder. That everyone was aware of this is also evident in my mother’s diary. Already in the beginning she mentions the persecution of the Jews and of mass murders. Radio Oranje has never called on the Dutch to help their Jewish fellow citizens.

Even my father neatly responds on 15 October 1940 to a request from occupier through the mayor and the town clerk of Ootmarsum to sign 2 forms, – with the subject “Government personnel Jewish blood”. On the letter he writes by hand that he signed them that same day.

WWII data Herman Budde

| Military examination | 15 November 1938 |

| Start military service in Hoorn | 12 January 1940 |

| Start of German occupation of the Netherlands | 9 May 1940 |

| Long furlough | 7 June 1940 |

| 1st Arrest Ootmarsum (prisons: Enschede/Almelo) | 9 June 1943 |

| Concentration camp Vught | 26 June 1943 |

| National prison Utrecht | 10 September 1943 |

| Release from prison | 2 November 1943 |

| 2nd Arrest Ootmarsum (prison: Oldenzaal) | 14 April 1944 |

| Work transport to Germany (to Nordhorn) | 17 April 1944 |

| Fled Germany (from Melle) | 30 March 1945 |

| Liberation of the Netherlands | 5 May 1945 |