I think there were two main reasons for Herman’s resistance activities:

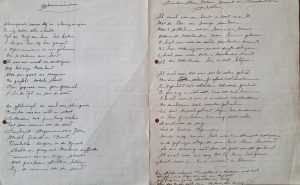

- First, he felt very strongly about freedom. This is especially evident in the few poems he wrote at that time.

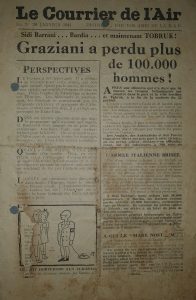

- He was part of a circle where he received illegal pamphlets which called for careful sabotage. The first date from the beginning of 1941 and have been preserved in his archives.

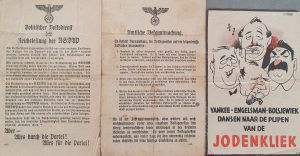

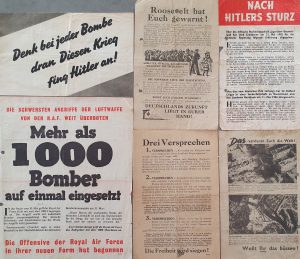

Soon he didn’t stop at writing poems and reading pamphlets and became involved in more active resistance (here are the full text in Dutch). He clearly was in contact with other like minded people and various resistance organisations, as indicated by the flyers that are in his archive. Several pamphlets came from resistance organisation for civil servants. Others call for boycotts and civil disobedience activities. Others provide inside information of the activities of the NSB from infiltrators. Full text of these flyers are in Dutch, archive numbers 19, 20a and b, 21 an 22 – use Google translate)

His friend and colleague Henny Lohuis was certainly also part of this circle. The extend to how much organisation there was between these people is unknown, but it looks like Herman’s activities were based on personal initiatives rather than on organised resistance. However, this issue keeps coming back during interrogations after his various arrests.

Already in May 1941 Herman was fined for putting up posters on top of those from the NSB, the National Socialist Movement in the Netherlands (Dutch: Nationaal-Socialistische Beweging in Nederland (NSB). These were Dutch people who collaborated with the Nazis.

NSB Posters affair

| The posters made by the NSB were regularly torn off and posted over with other placards. In May 1941, two citizens were found guilty of doing this, witness a letter that mayor H.F.M. baron Schimmelpenninck van der Oye received on 7 May 1941 from the Public Prosecutor (E.Overbosch) in Almelo.

It reads: “Following the police report of the Marechaussee Brigade Ootmarsum, drawn up against H.G.J. Lohuis and H.P.Th. Budde, concerning posting over of the posters of the NSB, in which it turned out that the pamphlets of the NSB had already been destroyed beforehand, I have the honour to ask you, Your Honor, to take adequate police measures, so that the repetition of such an act in the future is prevented.” (Source: Ootmarsum 1940-1945) |

It is also interested to read in the above mentioned pamphlets that the Marechausse – after it was reorganised by the Germans – fully cooperated. How this was done and what the consequences were explained and the key collaborators are all identified.

Cable Watch

Working at the town hall, Herman was soon the bobbin regarding the cable guard. His archive contains an overview in which his diagram is mentioned. In his archive there are also some calls for Herman’s father Theo (archive numbers 16 and 17).

Source: Ootmarsum 1940–1945

To ensure communication connection between the various components, the German occupying army had built its own telephone line. This was especially in the first years of the war very provisional and the cables lay unprotected and exposed along the roads.

It goes without saying that these cables were a popular target for the underground resistance and it happened repeatedly that the cables were destroyed. In addition, large pieces were often taken away and therefore recovery was made even more difficult.

The German occupier wanted to put an end to these acts of sabotage and had the cables protected by the so-called Cable Guard.

Dutch citizens were called in for the cable guard, who were forced to patrol a few hours along a predetermined route under penalty of reprisals. Those cable guard had to operate both day and night.

It is understandable that the enthusiasm for this work was not very great for several reasons and many tried to get out of it. If this were successful, for example by pretending to be an illness, it did result in others often having to work double shifts. Out of solidarity, therefore, many went on cable watch.

In Ootmarsum, a length of 2.4 kilometres of cable had to be guarded along, among others, the Almelosestraat, Molenstraat, Vasserweg, Hazelrot and Oldenzaalsestraat.

The times were: from 22.00 – 02.00 hours; from 02.00 – 06.00 hours; from 06.00 – 10.00 hours; from 10.00 – 14.00 hours; from 14.00 – 18.00 hours; from 18.00 – 22.00 hours.

Under the German regulations all male inhabitants between the age of 18 and 60 had to participate.

By order of the occupying forces, the Ootmarsum cable guard was set up in mid-September 1941 by mayor Schimmelpenninck van der Oye. From the beginning, there were certain groups of people who did not need to take action. These were primarily the NSB members; they didn’t have to do that work. The Jews were not eligible because, according to the occupier, they could not be trusted. Then all those who worked in German factories or at Hazemeijer, Heemaf or Stork also had an exemption. And finally, civil servants, doctors, the military police, , clergy and policemen were also exempt.

According to the regulations, a piece of cable had to be guarded for 4 hours. During the day it was 200 meters and at night 100 meters.

For what ever reason the cable watch was abolished by the end of 1941.

Next: The War Year 1942