Both Australia and the Netherlands were ill prepared for the rapid conquest of SE Asia by the Japanese. There were no plans or strategies in place until it became obvious that the invasion of Netherlands East Indies (NEI ) – and potentially Australia – was imminent.

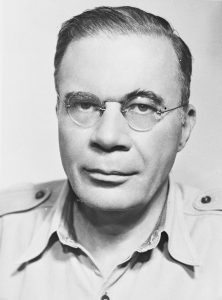

A month before the invasion by the Japanese of the NEI the Minister of Colonial Affairs Hubert van Mook [1] flew to Australia on January 6, 1942 to discuss the situation with the Australian Government. A Purchasing Commission was established in Melbourne to handle the supply of weapons and materials needed to assist in fighting the common enemy. At the same time further official diplomatic relationships were established between Australia and the NEI Government in Batavia and the Dutch government-in-exile in London. Within weeks official representatives from the countries were appointed and offices were opened in Canberra and Batavia. All to no avail as a few weeks later the NEI government capitulated. In April the Purchasing Commission was superseded by the NEI Commission. A key role was to discuss how to best handle all of the Dutch (military) ships, planes and other goods that arrived in Australia. Followed by negotiations of selling those military equipment to the Australian Government.

In January – just to make sure – 2000 Japanese citizens living in NEI were transported to Australia.

Immediately before and after the Japanese invasion on 1 March 1942, all aircraft from the privately owned Koninklijke Nederlandsch-Indische Luchtvaart Maatschappij – KNILM (Royal Dutch Indies Airways) with enough range were evacuated to Australia. On 7 March 1942, one day before the capitulation of Java, the last KNILM aircraft took off from the Boeabatoeweg in Bandung. A number of KNILM aircraft in Darwin were destroyed by the Japanese during the bombing of Darwin[2].

The last who left NEI included: Minister of Colonial Affairs Van Mook, his deputy Van de Plas[3], members of the Governing Council (Raad van Indië) and military leaders. They escaped to Broome[4] from Tjilatjap – the key port in southern Java – in March 1942.

They all had to leave their wives and children behind. Van Mook’s wife ended up in a Japanese concentration camp for the full duration of the occupation, but some of the Dutch women and children still managed to escape to Australia[5].

Large numbers of NEI warplanes, surviving warships as well as the government archives were rescued. Large numbers of soldiers and administrative staff had been able to flee to Australia.

With the Netherlands since 1940 occupied by Nazi-Germany, many senior Dutch business and government officials and military personnel in NEI evacuated to Australia. However, over 100,000 Dutch citizens ended up in the Japanese concentration camps and around 60,000 Dutch militarily personnel and other officials (teachers, doctors, engineers, etc) were made prisoners of war. The 50.000 Indonesians captured were released as they were Asian blood-brothers. Those imprisoned were all abused, mistreated and towards the end of the war many died of starvation, an estimated 21.000 people died in captivity. The relative few that escaped to Australia (20,000) were the lucky ones.

The Netherlands as no other country in Western Europe had such a large group of its citizens imprisoned by the Japanese. The trauma caused by such mass and long incarceration on ordinary people is still with us today.

It is also interesting to note that the first ship that had to flee to Australia had arrived in Brisbane in December 1941. The Dutch merchant Bloemfontein was part of a US convoy on their way to bring reinforcement to the Philippines. However, because of the Japanese blockage they never made that and the whole convoy docked in Brisbane on December 22 1941. US General Douglas MacArthur – in charge of the US command in the Philippines – ordered blockage runners from Brisbane to NEI and from there using smaller vessels to the Philippines. However, by the time this got organised the Philippines had fallen to the Japanese.

Uncharted territories for the Australians, Dutch and NEIs

The complexity of the situation is well described in chapter 2 of Dr. Jonathan Ford’s 1995 book Allies in bind: Australia and the Netherlands East Indies relations during World War Two.

As the Brits were sure that they could defend Singapore, The Netherlands (NEI) and Australian threw their full support (and resources) behind this campaign and both had significant losses at the expense of their our own defence. Within a week Singapore was lost and the Japanese now rapidly moved on to the NEI. When this country fell Australia became the safe haven for the military, airforce, navy – including the merchant navy – government officials, private NEI companies as well as individuals.

Of course, Australia was unprepared for this. There were a range of political, administrative, and financial issues. Also, each of the key players had their own political agenda. Here just a few of the key issues:

- The Netherlands didn’t want the NEI officials in Australia to advance more independence.

- Australia was eager to increase its relationships with NEI.

- Tug-of-war regarding NEI military equipment now in Australia.

- What arrangements need to be made regarding forward orders that were placed by the NEI/Dutch Governments.

- What is the position of foreign (NEI) companies who had fled to Australia?

- What arrangements need to be in place to safeguard government and private money (and gold) brought into Australia?

- How to deal with the cargo of Dutch and NEI ships stranded in Australia.

While Australia had problems with administrative and financial arrangements, they were eager to make contractual arrangements for NEI military equipment and other goods they desperately need to be used for their own war effort . However, often the US was stronger and able to claim most of that. Financial and administrative contracts between the Dutch and the US were often swift without unnecessary bureaucracy.

An anecdote to highlight the bureaucracy was a request that Dutch had made in January to give equal priority to Dutch and Australian Deference orders , this had gone backwards and forwards with an official reply of approved send to the Dutch at the beginning of April nearly a month after the capitulation.

The delivery of 200 round of ammunition for the KNIL Mauser rifles to their soldiers in Merauke required export permission and before that was given the paperwork for it had gone passed the Australian Departments of Agriculture, Army, Attorney General and External Territories.

On the Dutch side politics played a key role. Already before the war there was a steady development for more independence for NEI. The ministerial team that fled NEI lead by Hubert van Mook was one of the leaders of this group. They wanted to establish an organisation in Australia to look after NEI affairs. The Dutch Government in Exile in London was very wary of the possibility that this would be used to obtain more independence. The Dutch wanted all key decisions re NEI to be made in London and van Mook and his 2nd in charge van der Plas were rapidly moved from Australia to London to stop any movement towards more independence. He wouldn’t be able to return to Australia until September 1944 when he was appointed to lead the NEI Government-in-Exile, which replaced the NEI Commission.

An example of the bureaucracy in action here was the chartering of Dutch ships by the US and Australia. The Dutch in London were adamant that they would make such decisions and that negotiations should take place in London and not in Australia. The process dragged on for months, in the end the NEI Commission was given permission to handle the allocation, which the did in close cooperation with the KPM (see below) – being the owner of the ships , based in Sydney .

Australia wanted to have much closer relations with NEI, being its neighbour to the north. It also saw an opportunity to increase its influence in NEI because if the war situation. This led to a diplomatic tug-of-war between Australia and the Netherlands about diplomatic positions.

While all these issues played out, the overarching cooperation between Australia and the Netherlands remained very strong. Australia went out of the way to assist the Dutch and their hospitality was very much appreciated on all levels of the Dutch and NEI communities.

All of these issues are extensively covered in Jack Ford’s above mentioned book.

Collaboration start bearing fruits

Even as Australia was unable to claim all of the NEI military equipment the additions they received were a very welcome edition to Australia’s under resourced. Contractual arrangements led to a range of combined forces.

In all over 100 Dutch aircraft were transferred to the RAAF. This made a significant difference to Australia’s air force capability. This happened at a time when it was nearly impossible to obtain any air craft from the US or Britain. Four NEI air squadrons were formed from ML-KNIL personnel, under the auspices of the Royal Australian Air Force, with Australian ground staff, they were known as the RAAF-NEI squadrons. This greatly improved the overall Dutch-Australian war effort.

Twenty-one small KPM merchant vessels, loaded with refugees arrived in Australian ports and were consequently obtained by charter for U.S. Army use and became known as the “KPM vessels” in the US-led South West Pacific Area fleet. These ships comprised of almost half the permanent local fleet[6].

A total of approx.15,000 Dutch wartime evacuees were settled in Australia, of which 6,000 were of non-European heritage, however Rupert Lockwood, a Reuters journalist reporting on the NEI at that time estimates the numbers to be closer to 20,000 of which at least 10,000 were natives of NEI[7]. Most of the KNIL soldiers that arrived in Australia were natives of NEI, mostly from the island of Ambon[8]. It was culturally, geographically and politically very different from the main islands of the archipelago and was very much pro-Dutch. It was here that the VOC (Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie – Dutch East India Company) established their first head office in 1610 before it was moved to Batavia a decade later.

The logistics of this ‘Dutch invasion’ into Australia was massive, nevertheless, with great efficiency on both sides, this went rather smoothly. A major issue however was that as most of the evacuees where either native from the archipelago or people from mixed blood (Indos). This clashed with the White Australia policy. Under that regime the Dutch were not allowed to evacuate coloured people during the airlift operations from NEI to Australia and these people remained stranded. Australia however, couldn’t send the coloured people on navy and merchant ships back to NEI. They were reluctantly allowed them to stay under the strict rule that they all would immediately return to NEI after the war. When the Americans arrived they blatantly ignored Australia’s demand that no Black people would be allowed to come to Australia and tens of thousands of them arrived in Australia during the war.

Political ambitions of the local population in NEI

[1] Hubertus van Mook was born in Semarang in Java on 30 May 1894. As with many Dutch and ‘Indonesians’ growing up in the East Indies, he came to regard the colony – particularly Java – as his home. He died in France in 1965. Following the Japanese conquest of NEI in 1942, he was appointed as Acting Governor-General by the Netherlands East Indies government in exile. Another interesting aspect of van Mook is that he established in Melbourne a school for civil servants, to train a new generation of Indonesian administrators as a he envisaged the need for a different level of government to facilitate self-rule for the ‘Indonesians’. Ambonese war hero Samuel Jacobs was one of the first students. In 1944 he became Lieutenant Governor General of the NEI Government-in-Exile, based in Wacol, Brisbane. On 1 October 1945 Van Mook arrived back in Java along with others of the Netherlands Indies Civil Administration. However, their presence generated much outrage from much of the Indonesian populace who were opposed to the restoration of Dutch colonial rule.

On the Dutch side, Van Mook was considered “too lenient” and in November 1948 was dismissed (resigned) following differences with the Netherlands Government. He was one of the very few in government who foresaw and understood the unravelling of Dutch Colonial rule in the Dutch Indies.

[2] In all, 11 KNILM aircraft managed to escape to Australia: 3 Douglas DC-5s, 2 DC-3s, 2 DC-2s and 3 Lockheed Model 14 Super Electras. In mid-May 1942 the remaining aircraft were sold to the American military. See Allies in adversity, Australia and the Dutch in the Pacific War: No. 18 (NEI) Squadron, RAAF – Australian War Museum https://www.awm.gov.au/visit/exhibitions/alliesinadversity/australia/nei

[3] Charles Olke van der Plas was born in Buitenzorg (NEI) 15-5-1891 – he died in Zwolle, Netherlands 7-6-1977. In 1908 he went to Leiden University to prepare for the exam for the Netherlands East Indies government. In 1912 he started as an administrative official at the Binnenlandsch Bestuur (Home Affairs) on Java and became in 1913, one of its inspectors. Following his period as deputy or acting advisor for home affairs of NEI, he received assignments concerning education and colonisation. In 1932 he became a resident of Cheribon and at the same time chaired the Transfer Committee. This was essentially the task of completing the transfer of administrative powers from the central government to representative bodies with a large Indonesian majority. In 1936 he became governor of East Java. In this important province he was able to develop his creative managerial visions on a large scale, demonstrating his special interest in improving the social and economic situation of the ‘Indonesians’.

[4] An interesting historical link here is that this was not far from where Dirk Hartog in 1616 chartered the Australian west coast known as Eendrachtsland (Harmony land).

[5] Het Koninkrijk der Nederlanden in de tweede wereldoorlog 1939-1945 – http://loe.niod.knaw.nl/grijswaarden/De-Jong_Koninkrijk_deel-11c_bw.pdf

[6] They were: Balikpapan (1938), Bantam (1930), Bontekoe (1922), Both (1931), Cremer (1926), Generaal Verspijck (1928), Janssens (1935), Japara (1930), Karsik (1938), Khoen Hoea (1924), Maetsuycker (1936), ‘s Jacob (1907), Sibigo (1926), Stagen (1919), Swartenhondt (1924), Tasman (1921), Van den Bosch (1903), Van der Lijn (1928), Van Heemskerk (1909), Van Heutsz (1926) and Van Spilbergen (1908). Source Ship List Koninklijk Pakketvaart Maatschappij – http://www.theshipslist.com/ships/lines/kpm.shtml

[7] Rupert Lockwood – The Indonesian Exiles in Australia, 1942-47 https://www.jstor.org/stable/3350634?seq=1/analyze

[8] Ambon is part of the Moluccas. A large group of mainly privileged Ambonese wanted to be independent from the Republic and after WWII the Dutch promised them this independence; which they never received and which consequently led in 1951 to a mass migration of ethnic Ambonese people to the Netherlands, they were not happy that the Dutch had negated on their promise and this even led to them hijacking a train in the north of the Netherlands in June 1977.