At several occasions we have referred to the Trade Union boycott against the Dutch re-colonialisation of NEI, which subsequently became known as the Black Armada.

The running up to the boycott was rather straightforward. It begun with labour disputes over wages and this struggle continued throughout most of the 1942 -1945 period with a tardy Dutch Government reluctant to provide equal pay to NEI personnel.

Then in 1943 the Trade Union and the Communist Party became involved in the plight of the political prisoners the Dutch had brought to Australia. These prisoners became leading activists for the independence movement of Indonesia in Australia.

By the time the war ended the trade unions were ready to assist the ‘Indonesians’ in obtaining a greater say in their future. In order to make the planned boycott a legitimate trade union issue their political support was linked to demands that any deferred pay and retention would be based on the non- colonial wage rates as they had been negotiated in Australia. The Dutch refused to go into such an agreement.

As a result, on 20 September 1945, the first embargo on Dutch ships was proclaimed in Brisbane, followed by Freemantle, a few days later Sydney and Melbourne followed (hospital ships were exempted).

The boycott was not limited to Dutch shipping but also applied to air transport, trade, repairs and storage. As reported by Rupert Lockwood[1], over the two-year period it effected: nine corvettes, 2 submarines, 7 submarine chasers; 36 Dutch merchant ships, passenger liners and troop transport ships; two tankers and 35 other oil industry craft; 450 power and dumb barges, lighters and surf-landing craft; aircrafts and land transport vehicles. Furthermore, two British troopships and three Royal Navy vessels were blacklisted. In all 559 vessels and 1.000 land crafts have been identified as being affected by the ban of the 31 trade unions involved in the boycott.

The boycott was actively supported by Asian trade unionists especially Indian and Chinese workers. One of their leaders Fred Wong[4] features in the documentary film “Indonesia Calling”.

An Australian public opinion poll at the end of 1945 showed that 60% had read about the situation in the Netherlands East Indies in the press. Of these, 40% favoured Dutch rule because the Dutch had done a good job and the ‘Indonesians’ were not yet ready for self-government. Some 30% favoured independence because the ‘Indonesians’ had been exploited and, besides, self-rule was the right of all people. The remaining 30% either opted for joint rule or simply didn’t know what to think.

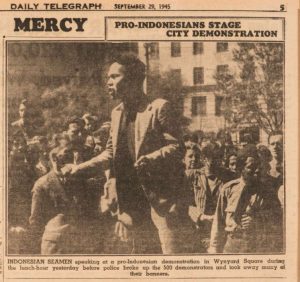

In Sydney – as documented in the Joris Ivens film – there was on 30 September 1945 a rally for Indonesia attended by over 5,000 people, all showing support for their northern neighbours. More public rallies – many supported by the churches – followed, all demanding the Dutch to hold up the Atlantic Charter[5]. This support was especially significant as at the same time the country had a strong anti-Asian policy in place, known as the White Australia Policy, this banned non-Europeans from settling in Australia. However, this official policy clashed with an important Australian sentiment that of supporting the under-dog, here being the Indonesian people.

At the same time however, the Australian Government kept supporting the Dutch and, on several occasions, proclaimed that actions taken by the Dutch – with force or not – were not subject to Australian (military) law. The Dutch – under the extraterritorial rights they had received from the Australian Government – could act as they saw fit.

These Australian concessions to the Dutch Government were attacked by the trade unions and remarkably the unions were able to boycott the use by the Dutch of eight corvettes the Australian government had sold to the Dutch Navy.

It is important to note that not all of Australia supported the Indonesian cause, a significant part supported the re-colonialisation of NEI. The opposition to the position of the unions was led by conservative political parties under the leadership of Robert Menzies, as well as by the mainstream Australian press and the business establishment. They strongly condemned the Black Armada boycott.

There was a serious incident in 1946. Following the death of two people in the prison camp in Casino – one possibly a suicide – the ‘Indonesians’ in the prisoners refused to work for the Dutch recolonialisation effort. This drew a violent reaction from the Dutch military. On 12 September the Dutch prison guards opened fire at a protest by the Indonesians. One defiant ex-soldier named Soerdo was shot dead and two others wounded. Sympathisers, Casino residents and the press were outraged.

The incident was an embarrassment for the Australian Government, they demanded the closure of the camp. This nearly led to a diplomatic incident between the two countries. Eventually in November that year the camp was closed[6].

By mid-1946 the Australian boycott petered out and the last ships and warplanes left Australia. Australia remained – be it conflicted – an important stronghold for the Dutch in their ongoing efforts to recolonise NEI.

While the boycott didn’t stop the reconquest of NEI, the delay in the recolonialisation worked in favour of the new republic, something that later was acknowledged by successive Indonesian governments. In the end of course, it was the desire of the Indonesian people to be independent that brought about their freedom from colonial rule.

The boycott was revived twice, first during the so-called Dutch ‘police actions’ against the self-proclaimed Republik of Indonesia in 1947 and 1949 and secondly in 1960 during the New Guinea crisis when the aircraft carrier Karel Doorman and its escort on their way to what is now Papua were black listed.

The boycott remains one of the largest in global maritime history.

[1] Rupert Lockwood – Black Armada https://trove.nla.gov.au/work/26436607

[2] Ivens came to Australia in early 1945 as the NEI Film Commissioner, to document the re-colonisation effort of the Dutch Indies from Australia. He was employed by the NEI Government Information Service (NIGIS) in Melbourne they had 128 staff—25 of these ‘Indonesians’—(a branch office of three in Sydney), and a further 24 journalists and stringers attached as war correspondents. However, Ivens defected and started as an independent film maker to document the Indonesian struggle for independence, resulting in his Dutch passport being revoked by his government. He moved from Melbourne to an apartment in Birtley Towers in Elizabeth Bay Road, Sydney. The movie premiered on Kings Cross in August 1946. The Dutch Government tried to stop screening elsewhere in Australia and asked for an export ban, this was initially granted but overturned a month or so later. It then screened in New York and London as well as Indonesia and New Zealand. The film was instrumental in internationalising the Indonesian cause and it supported the strong relationship that was building up between Australia and its neighbour Indonesia. Ivens left Australia in 1947. In 1985, his work was finally recognised by the Dutch Government, who offered him an apology and awarded him the highest Dutch film award the ‘Golden Calf’. This documentary had a profound impact on documentary making in Australia and it encouraged discussions about censorship, politics, national security, international relationships, film regulations and communism/cold war issues, with numerous people involved in these discussions at the highest levels: politician, bureaucrats, military, film makers, and many others. It opened up a range of issues around film making that were very specific for a rapidly growing up Australian film industry that up to than was basically based on British examples (After Indonesia Calling – John Hughes https://researchbank.rmit.edu.au/eserv/rmit:161199/Hughes.pdf).

[3] Indonesia calling — Joris Ivens, 1946 –

[4] One of the strong supporters of the ‘Indonesians’ was Fred Wong, a Chinese Australian who lived in Leichhardt and had a greengrocer’s business on Parramatta Road. He features in the movie as a strong supporter for the Indonesian cause. His commitment to the Indonesian cause was amazing, he started a company Air Asia to support Indonesia with food and medical supplies, this enterprise however, was boycotted by the Australian Government as the world was rapidly entering the Cold War and Fred was seen as far to leftish but nevertheless, he was able to launch the service with one Catalina. In 1948, on his way with food and medicine to Indonesia on a stopover in Lake Boga (Victoria) he drowned in what many suggest were suspicious circumstances.

[5] The Atlantic Charter was a pivotal policy statement issued during World War II on 14 August 1941, which defined the Allied goals for the post war world. The leaders of the United Kingdom and the United States drafted the work and all the Allies of World War II – including Australia and the Netherlands – later confirmed it. The Charter stated the ideal goals for after the war—no territorial aggrandisement; no territorial changes made against the wishes of the people, self-determination; restoration of self-government to those deprived of it; reduction of trade restrictions; global cooperation to secure better economic and social conditions for all; freedom from fear and want; freedom of the seas; and abandonment of the use of force, as well as disarmament of aggressor nations. Adherents of the Atlantic Charter signed the Declaration by United Nations on 1 January 1942, which became the basis for the modern United Nations. The Atlantic Charter set goals for the post-war world and inspired many of the international agreements that shaped the world thereafter. The General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), the post-war independence of European colonies, and much more are derived from the Atlantic Charter. Source Wikipedia

[6] De Indonesische revolutie op Australische bodem https://javapost.nl/2015/11/12/de-indonesische-revolutie-op-australische-bodem/