When the Japanese landed in Hollandia on 6th of May 1942 the Dutch, in their haste to flee, failed to blow up their facilities so they ended up undamaged in the hands of the Japanese. However, after they took what they wanted the Japanese scorched the place and then simply left.

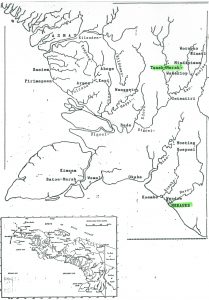

The southern part of New Guinea was not occupied by the Japanese, although the Dutch were concerned about their advance. If the Japanese were to also occupy that part of the island, they were worried that the political prisoners held in Tanah Merah would ban together with the Japanese, in exchange for recognition of greater independence..

In 1943 the Dutch decided to transport these prisoners to Australia. This was the start of an important episode that brought the political situation of the Dutch colony under the attention and scrutiny of the Australians.

Earlier, a few of the prisoners had escaped and fled to Australia across the Arafura sea that separates the two countries. Australia was therefore aware of the existence of this camp. The escapees had been sent back to the camp. Australia supported the Dutch rule of NEI and was never interested any further in the affairs of the northern neighbour.

One of history’s most amazing escapes

| There is a harrowing story of 4 prisoners escaping from Tanah Merah. Three of them survived the trip through 200kms of jungle – one was speared by a Papuan warrior on the way and later died. The other three arrived in Merauke and were cared for by the Melanesian population there and they received a canoe and ended up on Thursday Island. The escapees were able to hide themselves among the locals and even opened a shop (hairdressing)[2]. However, they were eventually picked up by the Queensland authorities and handed over to the Dutch. Trade unionists in Darwin petitioned the Australian Government to provide political asylum to these political prisoners but under the ‘White Australia policy’ that was cruelly refused. They ended up in the even more infamous Tanah Tinggi[3] concentration camp, just outside Tanah Merah.. One of them Abdul Rachman was one of the prisoners who arrived in Australia for a 2nd time, this time brought by the Dutch (see below). In Australia Abdul became a student at an English language class for ‘Indonesians’ conducted by English teacher Mrs Gwyn Williams from Darlinghurst, who wrote down the stories of the students. Her teaching greatly assisted her students to far more effectively communicate in Australia and to create effective propaganda materials. There were several escape attempts to either Australian Papua New Guinea and one more to Australia (Thursday Island) but none of them were successful. In most situations they were captured or killed by Papua’s. |

The Dutch considered it safer to bring the political prisoners to Australia and in mid-1943 and they were supported by the Americans. This support was used by the Dutch to lobby for the Australian Government to achieve permission to bring them to Australia. Again the White Australian policy stood in the way, but finally they were allowed to be brought to camps outside the main cities. To the Australians these prisoners were presented as dangerous guerrillas rather than political prisoners.

Charles van der Plas was send to Merauke to organise the evacuation. He had to travel 200kms over the Digul river to Tanah Merah – deep into the mosquito invested jungle. The prisoners had no idea that there was a world war going on and that the Japanese had taken over most of NEI. A few old and sick prisoners were left behind as the Dutch reasoned that they would be of no use to the Japanese.

Prisoners of Tanah Merah included Mohammad Hatta and Soetan Sjahrir (they later became the first vice president and premier of the Indonesian Republik).

Interestingly after the invasion of NEI by the Japanese, the Dutch Governor van Mook offered Sjahrir – seen as a moderate nationalist -passage to Australia. He indicated that he would only accept this if the rest of the Tanah Merah prisoners would be set free, that of course didn’t happen, at least not by the Dutch.

The evacuation was a difficult and tedious affair. In all 295 political prisoners plus another 212 women and children as well as 40 guards. They all had to travel over the Digul River to Merauke. From here they were flown to Horn Island by Dutch Catalina seaplanes. A group of 22 internees – most likely the most senior ones where immediately transported on the Katoomba to Sydney. N0n-internees (women and children) were brought by ship to MacKay, where they were accommodated..

The rest of internees themselves came to Australia cramped in the Dutch KPM steamer ‘Both’. After departure from Merauke the ship docked for fresh supplies in the Queensland port of Bowen. From there it travelled to Sydney and after disembarking the prisoners went to Central Station and were transported by train to Liverpool on the outskirts of Sydney. Others were transported further to the prisoners-of-war camp in Cowra. Here they became known as the “Digulists” (back in Tanah Merah all people, prisoners and non-prisoners referred to themselves this way).

The Dutch kept very quiet about the prisoners, the trip and what happened with them afterwards. Most of the following information comes from Australian sources and above all from the already earlier mentioned Reuters reporter Rupert Lockwood[4].

The Dutch kept very quiet about the prisoners, the trip and what happened with them afterwards. Most of the following information comes from Australian sources and above all from the already earlier mentioned Reuters reporter Rupert Lockwood[4].A second handwritten note from one of the original Indonesian railway strikers from 1926 – known to the Australians as Jo-Jo – reached the Civil Rights League in Sydney. This note mentioned the many sick (malaria) and asked for medical attention. (Jo-jo suffered from tuberculosis and died soon after his arrival in Sydney). The information reached some of the Australian soldiers who together with Dutch soldiers were involved in guarding the camps where these political prisoners were held. Once the Australians had established that these people were no friends of the Japanese, food and fruit parcels as well as medicines were rapidly organised for them. Laura Gapp of the Civil Rights League alerted the Australian Government about this situation. While there was not an instant result a process was started that a few months later would lead to the release of the prisoners.

The Dutch had been less than honest when they informed the Australian authorities that these prisoners were enemies of the allied forces and therefore had to be treated as prisoners of war. When that turned out not to be true, the Dutch were forced by the Australian Government to transport the sick to the Dutch Princess Juliana Hospital in Turramurra.

It was clearly seen as inappropriate for Australia to jail political prisoners from another country. Soon after the release of the sick, the rest of the prisoners in Liverpool were set free. Finally, on December 7th, 1943 the detainees in Cowra were also released. Many of the freed prisoners joined trade unions. The result of this was that more Australians – especially trade-unionists – got a better understanding of the plight of the ‘Indonesians’.

Once freed most of them went to a for them more climate friendly North Queensland. Some worked on the sugar plantations and others worked for the Dutch military forces in Mackay. It was here that they formed one of the first Indonesian Independence Committees in Australia, known as the Mackay Committee.

They would become the driving force behind the request for a boycott of Dutch ships. With the Dutch NEI Government-in-exile now concentrated in Brisbane (Wacol), the central office for the Indonesian independence movement was also established in Brisbane to coordinate the various independence activities in Australia.

It is rather ironic that after all the effort to keep the Digulists out of the hands of the Japanese, so they could not use the occupation to continue their fight for independence, they became potentially an even more potent force for the independence thanks to the Dutch bringing them to Australia.

The Gamelan Digul was brought to Australia

[1] Tanah Merah Concentration Camp http://paulbuddehistory.com/annie-budde-in-nieuw-guinea-in-dutch/tanah-merah-concentration-camp/

[2] Boven-Digoel – L.J.H. Schoonheyt https://www.papuaerfgoed.org/files/schoonheyt_1936_digoel.pdf

[3] Tanah Merah Concentration Camp http://paulbuddehistory.com/annie-budde-in-nieuw-guinea-in-dutch/tanah-merah-concentration-camp/

[4] Rupert Lockwood – Black Armada https://trove.nla.gov.au/work/26436607