American-British-Dutch-Australian Command

The American-British-Dutch-Australian (ABDA) Command, or ABDACOM, was a short-lived, supreme command for all Allied forces in Southeast Asia, the area also included the supply port of Darwin, in the Northern Territory, Australia.

ABDA had been established at Bandoeng, Java on 10 January 1942 and became operational following the declaration of war by Japan on 12 January 1942.

The main objective of the command, led by British General Sir Archibald Wavell, was to maintain control of the “Malay Barrier”, a notional line running down the Malayan Peninsula, through Singapore and the southernmost islands of Dutch East Indies. Although ABDACOM was only in existence for a few weeks and presided over one defeat after another, it did provide some useful lessons for combined Allied commands later in the war.

Its theatre of operation was huge, but its force was thinly spread , covering an area from Burma in the west, to Dutch New Guinea (DNG) and the Philippines in the east. The western half of northern Australia was added to the ABDA area.

The reason why the Dutch participated in ABDA and therefore relinquish direct control over its own forces was based on two promises.

- The Brits were certain that they could defend Singapore and that this would stop the Japaneses moving on to NEI.

- ABDA promised that reinforcement would become available if needed for the defense of NEI.

-

The promise of substantial reinforcements which never arrived.

ABDA was launched on shaky grounds. There were no previous arrangements between the four nationalities, they used different equipment and had not trained together. The countries also had different priorities of the national governments.

- British leaders were primarily interested in retaining control of Singapore.

- The military capacity of the Dutch East Indies had suffered as a result of the defeat of the Netherlands in 1940, and the Dutch administration was focused on defending the island of Java.

- The Australian government was heavily committed to the war in North Africa and Europe, and had few readily accessible military resources.

- The US was preoccupied with the Philippines, which at the time was a U.S. Commonwealth territory, also General Douglas MacArthur took little notice of ABDA and operated on his own.

While the coalition went from loss to loss there were a few successes.

The ABDA attack led by the U.S. Navy at Balikpapan, Borneo on January 24, costed the Japanese six transport ships, however it had little effect on them capturing the prized oil wells of Borneo. However, the defence force was able to destroyed the at that time largest oil refinery in the world and it was not until later in 1944 before the Japanese were able to bring production back to pre-war levels.

Perhaps the most notable success for ABDA forces was the guerrilla campaign in Timor, waged by Australian and Dutch infantry for almost 12 months after Japanese landings there on February 19.

An other unit was able to defend the airfield of Babo (DNG) long enough to destroy it before the Japanese reached it. Sadly the non-white workers were not allowed to join the evacuation of the force because of Australia’s White Policy.

After the fall of Singapore, British interest and its capabilities in ABDA started to waver. While the Dutch had thrown in their equipment (and lost most of it) for the defence of Singapore, they got little in return now NEI became the Japanese next target.

From 15 February onward, Japanese bombers attacked the capital Batavia (now Jakarta) and government operations were removed to Bandung. The promised reinforcement from the other Allies never eventuated. This also had a major effect on the Battle of the Java Sea (27 February 1942).

Following the destruction of the ABDA naval strike force under Rear-Admiral Karel Doorman, at the Battle of the Java Sea, ABDA effectively ceased to exist.

Battle of the Java Sea

|

This was part of a 13 day battle which started on 27 February 1942, and was directed by ABDA under the command of Wavell. Allied Navies suffered a disastrous defeat in the Java Sea at the hand of the Imperial Japanese Navy, and in secondary actions over successive days. The ABDA Strike Force commander— Dutch Rear-Admiral Karel Doorman—was killed. The Dutch surface fleet was practically eradicated from the Asian waters. However, this battle did slow down the Japanese expansion. If air support had been given by the other allied forces this battle could have turned out differently, without that support the ships were sitting ducks as the Japanese air force pinpointed their positions. On the Allied side, two light cruisers and three destroyers were sunk, one heavy cruiser was damaged and 2,300 sailors killed. On the Japanese side, one destroyer and one transport ship were damaged and 36 sailors killed. The aftermath of the battle saw several smaller actions around Java, including the smaller but also significant Battle of Sunda Strait. While the ABDA losses were heavy it is also important to note that the Battle of the Java Sea took longer than the Battle of Singapore and it did delay the Japanese advance. |

British and American forced started to withdraw and the Dutch and Australians were left on their own. Wavell abandoned ABDA and left for Ceylon on February 25. Several totally under resourced units kept fighting till the bitter end, supported by what ever was left of the NEI air and naval forces. On a few occasions they were able to incur significant losses on the side of the Japanese, who retaliated by killing all Dutch and Australian POWs and often also the civilians who had supported them.

While there were such heroic events at the same time the Australians rightly bitterly complained about the KNIL. The NEI Army mostly consisted of local voluntary militias units with little or no training, there was a shortage of guns, ammunition and vehicles, let alone more serious material. Communication was often non existence and local post offices had to be used to relay messages. This also stopped functioning when the national telecoms infrastructure was bombed out of order by the Japanese.

On Sunday, 8 March, Lt. Gen. Hitoshi Imamura met with the Governor-General of the NEI, Jonkheer (Lord) Alidius Tjarda van Starkenborgh Stachouwer and set a deadline for an unconditional surrender. Lord van Starkenborgh ordered the Dutch troops to cease fire in a broadcast at 1pm the next day. The other allied forces surrendered on 12 March. Because poor communications some small units did fight on for a few more days, a few disappeared in the jungle and stayed there for years.

Dr. Jack Ford made up the balance in his book Allies in Bind: Australia and the Netherlands East Indies relations during World War Two.

The loss of the NEI was a disaster for the Dutch, greater than the loss of Malaya to Britain, or the Philippines to the USA. Only northern Sumatra, the Arafura Sea Islands, DNG and the Dutch West Indies remained under Dutch control. The Dutch fought a series of battles for three months with minimal British and US support. Britain lost 10 warships, a light tank squadron, five AA regiments and about 100 aircraft. The US lost 12 warships, an artillery battalion and about 140 aircraft. Most of their naval losses occurred evacuating not defending the NEI. Having smaller resources, Australia lost 5 battalions plus support units, about 40 aircraft including 3 QANTAS flying boats, Perth and Yarra. Left behind were 1,075 Australian prisoners of war on Ambon, 1,137 POWs on Timor and 2,736 POWs on Java. Their uncertain fate left some Australians bitter towards the Dutch throughout the war. The Dutch bore the brunt of the fighting. Their losses were irreplaceable, being most of their navy (87 warships), nearly all their 300 planes and the entire KNIL (121,000 troops). For the Dutch, who lost everything, only Australia put in a strong effort to support the NEI whereas US and British losses were comparatively low.

Japanese losses of 11 warships, 20 merchant vessels, 8 small ships and 20+ motorized barges were greater than in the Philippines or Malayan Campaigns. Japanese air losses were similar in the NEI and Malayan Campaigns (120 and 171 aircraft destroyed respectively). Japanese army losses were light (255 soldiers) compared to losses of 3,833 soldiers in Malaya, but the Japanese army only fought on Java. Marines were used in most invasions. Paratroop losses were heavy. Japan had a single paratroop battalion, dropped at Menado, Palembang and then Timor. While transport losses were few (about 6 planes), at least half of the battalion became casualties in the three operations. Only 78 paratroops survived the Timor operation, while at Palembang they suffered a 25% casualty rate on the first day. The paratroops would not be employed again until 26 November 1944.

It is also important to note that the Dutch did not command the major battles that in the end resulted in the loss of NEI, These were ABDA battles under the control of the British General Wavell.

Jack continues this story in his book as follows:

The Japanese who won the NEI Campaign can have the last word on the Allied defeat. Japanese invasion force commander General Imamura stated that:

The greatest mistake of the Dutch Government …concerning the defence of the East Indies seemed to be that it transferred supreme command in the Dutch East Indies from the Governor-General to General Wavell of Britain, who commanded only 10,000 British and Australian forces altogether. In fact, General Wavell fled to India by air when the Japanese troops began to land and move forward in East and West Java, leaving the Allied forces behind. As a result, the remaining Allied forces did not follow the lead of Commander ter Poorten at all, making it very difficult for him to carry out his strategy. I think it was natural that the commander lost the will to fight. Had the Allied forces in Java been commanded by the Governor-General, the Japanese army would have had to face a tough battle.

Australian troops still in Java were only informed about the Dutch surrender three days after the event, by that time it was too late for them to escape back to Australia and many were captured by the Japanese. Also KNIL units on Sumatra, Borneo, Celebes and the northern part of DNG kept on fighting. A key contribution that they made to the war effort was to destruct oilfield plants, airfields and ports. Some of the oilfields took many years to bring back to full operation, by that time the war was nearly over for Japaneses. This severely hampered the supply of the all important oil for their war machine. While the Japanese did get hold of most of the oilfield in British Malay, the Dutch had been able to do a more thorough demolition job in NEI.

The sad story for them was that as the British and Americans had abandoned ABDA there were no resources anymore available for the Dutch to undertake rescue missions to evacuate these stranded troops. They were either captured and killed by the Japanese or became POWs to be used as forced labour. Some units operating on northern parts of DNG were able to retreat into the jungle and island hop to eventually find other units that could assist in evacuating them to Darwin, others joined units still operating on the smaller islands.

Thousands of Dutch (37.000) and Australian (22,000) servicemen ended up at the Burma–Thailand Railway, and worked in factories in Japan. They experienced extreme harsh conditions, inadequate food and forced labour. By the end of the war, some 8,000 Dutch and just over 8,000 Australian prisoners of war had died of disease, starvation or ill-treatment in Japanese hands.

Over 100,000 Dutch civilians, particularly women and children, were also interned by the Japanese, in exceptionally cruel conditions, for the remainder of the war. More than 13,000 died. After the war, thousands were send to Australia and New Zealand for a 3 or 6 months recuperation period . After their release, many former internees settled in Australia. For many the nightmare was not over after the Japanese defeat. Indonesian Nationalists kept Dutch people in the concentration camps in the areas they controlled. Many were only released during 1946 when the Allied Forces where able to take over control.

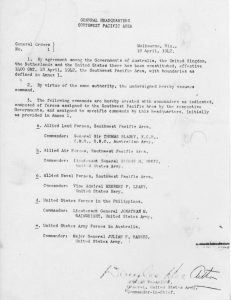

After the abandonment of ABDA there was a vacuum on the SE Asia war theatre and it was not until April that President Roosevelt announced the formation of South West Pacific Area (SWPA), after MacArthur had fled to Australia and on the 30th of March he was appointed to Supreme Allied Commander South West Pacific Area, a command which included Australia and New Guinea in addition to Japanese-held areas.

The inter-governmental Pacific War Council was established in Washington on 1 April but remained largely ineffectual due to the overwhelming predominance of U.S. forces in the Pacific theatre throughout the war. The Dutch and Australian often complained that they were not involved or consulted in decisions made by the Council.

Those who were able to fled NEI and those stranded on ships – including members of the KNIL – were housed in re-grouping and training camps under the direct command of Dutch officers in Melbourne, Sydney, Brisbane and Casino.

Following the surrender there was one more military action which took place In late 1942. The KNIL tried to land in East Timor, to reinforce Australian commandos who were waging a guerrilla campaign, however it failed and ended with the loss of 60 soldiers [1]. Guerrilla activities from combined Australian and NEI (stranded) soldiers on the island continued for nearly another year.

The Z Special Unit kept operating in certain parts across the archipelago. This was a joint Allied special forces unit formed during the Second World War to operate behind Japanese lines in South East Asia. Predominantly Australian, it was a specialist reconnaissance and sabotage unit which included British, Dutch, New Zealand, Timorese and Indonesian members, predominantly operating in the NEI. Their involvement in the war was one of the most successful of the combined Australian-Dutch operations .

Estimated Dutch losses during the battles in SE Asia between 1941 and 1942 are as followed:

- 1 gunboat

- 2 heavy cruisers

- 1 seaplane tender

- 15 destroyers

- 3 light cruisers

- 1 coastal defense ship

- 1 oil tanker

- 5,000-10,000 sailors and Marines killed on the sunken ships

- 100,000+ captured

Dutch protest re handing over planes to the Americans

|

There is an interesting anecdotal here. Dutch pilots were not happy that their planes were transferred to the Americas. As a protest, to show that they could outdo the Americans, they flew in formation under Sydney Harbour Bridge before the planed were handed over to the Americans at Archerfield Airport in Brisbane. Read the full story here. |

It is also important to put the NEI War effort into perspective. The NEI air force and navy fought for nearly three month in the SE Asia war theatre. The Malay and Singapore war was ended within weeks. The Netherlands in the mother country only fought for nine days. There were significantly more NEI people killed in the war than Dutch people. In general the NEI war has largely remained hidden from history because of the political colonial developments after the war. The reason MacArthur wrote to Roosevelt was that there was insufficient qualified staff from these two countries. Another hampering element was that the command of the Dutch and NEI forces was based in Ceylon, where its commander Lieutenant Admiral Conrad Helfrich was based. He delegated Ludolph van Oyen, Chief of Staff of the Royal Netherlands East Indies Army, as his representative in SWPA. Van Oyen was most of his time during the war in the USA. Rear-Admiral Coster assumed command in Australia, he resided in Melbourne. In his book Jack stated that by 10 June 1942, Coster’s command totaled 1,353 personnel comprising 207 officers, four midshipmen, 18 warrant officers, 241 non-commissioned officers, 144 corporals and 739 ratings/other ranks.

McArthur supported Helfrich’s suggestion to consolidate Dutch Command in Australia, but the Dutch Government-in-Exile in faraway London refused this request.

Dutch merchant fleet proved to be the major contribution to the Allied Forces.

While the overall Dutch combat contribution to the war in South East Asia was limited, its transport contribution to the war effort with ships, aircraft and flying boats to the Allied Forces was very significant. It contributed more ships than the other allied forces combined.

With the shipping fleet of the Koninklijke Paketvaart-Maatschappij – KPM (Royal Packet Navigation Company) being one of the largest in South East Asia its ships played a key role in assisting the Dutch, British and Australian war ships with the protection of Malay and Singapore. During the Battle of the Java Sea, KPM ships also assisted with the supply of ammunition. In the Netherlands East Indies (NEI), several of KPM ships were leased by the Royal Netherlands Navy to participate in the defence of the Netherlands East Indies. Th merchant fleet and their sailors paid a high price for their participation in the war.

During the Japanese Malayan Campaign (8 December 1941 – 31 January 1942) KPM ships were involved in the movement of supplies and troops aimed at the defense of Singapore. In January 1942 plans were made for the ship Aquitania to transport troops from Sydney to Singapore, it was escorted by the cruiser Canberra. In all 3,456 troops left Sydney on January 10th. However, concern about putting such a large and valued transport in danger of Japanese air strikes led to the decision to divide the troops over smaller KPM vessels[1]. The transfer took place at Ratai Bay in the Sunda Strait, between Java and Sumatra. The convoy reached Singapore on 24 January. The Battle of Singapore only lasted a week and the city state fell on February 15th. Australia could now no longer depend on the British Forces to defend their country. Arrogantly the British Government had convinced Australia and the Netherlands to provide full naval and airforce support as Singapore would never fall and therefor NEI and Australia would be safe. This massive defeat marks the start of the end of the British Empire. Dutch and Australian losses severally impacted the defence of their own countries. As the British had only made vague promises to assist the Dutch in the defence of NEI, their involvement remain half-hearted, of course also hampered by their enormous losses in Singapore.

After the Fall of Singapore KPM ships reaching Australia and were, after the collapse of ABDA, incorporated in the newly formed Southwest Pacific Area (SWPA) Allied Forces under Douglas MacArthur. They became part of a fleet being assembled in Australia for the support of the defense of Australia and the campaign against the Japanese in the SWPA. The crews of the KPM vessels fighting on the allied side were mainly made up of Indo- Europeans of the NEI. Only the very senior officers were Dutch.

Most of the vital reinforcement of New Guinea in 1942 and 1943, including troops, vehicles, weapons and supplies for the Milne Bay, Buna and Gona operations, was undertaken by Dutch vessels. The operation collectively known as Operation Lilliput, used the KPM vessels Balikpapan, Bantam, Bontekoe, Both, Cremer, Janssens, Japara, Karsik, Maetsuycker, Patras, Reijnst, s’Jacob, Swartenhondt, Tasman, Thedens, Van den Bosch, Van Heemskerk, Van Heutz, Van Outhoorn, Van Spillbergen, and Van Swoll. In all 39 convoys run in 40 separate stages under Operation Lilliput. Delivereing over 3800 reinforcements and 60,000 ton of supplies.

The Dutch Merchant Seamen and specifically those from the KPM – were recognised by General MacArthur for being pivotal to the success of the mission, the first battle in the South Pacific War where the Japanese were defeated. MacArthur had requested the support of the US Navy for landing boats for the operation, but he didn’t receive them. There were significant ship and crew losses as the operation received no air support and thus were easy target for the Japanese fighters. Dr Jack Ford has written an excellent article on the Dutch Merchant Fleet.

KPM also assisted by the former Shell tanker Ondina supplying the famous and successful MV Krait in the ‘Jaywick’ mission by the Australian Z Force. in September 1943 the Z Force was successful in sinking several Japanese ships in the harbour of Singapore..

In addition to the valuable role played by Dutch merchant seamen in maintaining supply lines between Australia, New Zealand, Britain, India and the USA. On one of these voyages the ship the Tjisalak was torpedoed by the Japanese and all of the survivors in lifeboats, including civilians, were brutally massacred by the Japanese.

In addition to the valuable role played by Dutch merchant seamen in maintaining supply lines between Australia, New Zealand, Britain, India and the USA. On one of these voyages the ship the Tjisalak was torpedoed by the Japanese and all of the survivors in lifeboats, including civilians, were brutally massacred by the Japanese.

During the war, the modern liner Oranje (built in 1939) was refitted as 1st Netherlands Military Hospital Ship, was another significant contribution to the war effort. With the Netherlands and NEI occupied the Dutch could no longer maintain the ship and it was offered by the Dutch government to the Australian Governments in May 1942. The Dutch did continue to provide medical staff as well as the ship’s crew. After Australia had repatriated its wounded military from the Middle East. In 1943 the ship was handed over to New Zealand, Oranje eventually carried more than 32,000 sick and wounded Allied patients on over 40 voyages. At the time it was the fastest hospital ship in the world.

The Dutch Navy was instrumental of what is now known as the US Seventh Fleet. Based on the above problems that MacArthur faced in establishing a proper US Naval Force in the Pacific, US Admiral King announced in March 1943 the formation of a fleet to support MacAthur’s SWPA Command. It started off as a small fleet of US, Australian and Dutch warships. Two third of the fleet’s cruisers were Dutch ships and included the Tasman which was converted into a hospital ship As the Australian Navy was preoccupied in the Indian Ocean, Dutch ships were used to patrol the west coast of Australia, the area some 300 years earlier explored by their forebears.

Flying boats

| During the 1930s the Dutch had built one of the largest fleets of flying boats, they were largely used in NEI. These planes were critical in a time when proper airstrips were still a rarity, especially beyond the major cities. The Flying Boat ‘airport’ in Rose Bay in Sydney is one of the last reminders of this era. The Dutch fleet were mainly Dorniers, originally build in German but later under license manufactured by Aviolanda in the Netherlands. The British and Americans predominantly used US build Catalinas By the time the Japanese started the war in South East Asia, the Dutch flying boat fleet (90 planes) was larger than the British and American fleets combined, several planes were therefore lent to British and American forces during battles in Singapore, Malaysia and the Philippines. The planes were used for reconnaissance and naval rescue operations, but they also successfully bombed a Japanese flying boat as well as a cruiser and were able to delay Japanese invasions, enough for people to be able to flee and for installations to be destroyed before the Japanese landed. With the Japanese advances the flying boats withdrew to Java and after the surrender of the Dutch East Indies the remaining planes were flown to Roebuck Bay in Western Australia. |

As we will see later most of what was left over from the fleet of flying boats fled to Australia after the fall of NEI. See: The Drama of Broome

Fighting continued on the outer islands

An element that is often overlooked is that while the government in Batavia had capitulated the fight on the smaller islands especial in the Arafura Sea and at Dutch New Guinea continued during 1942 and 1943. While in the end they were unable to win the battles against the Japanese they were able to delay their march forwards and were able to pass on important intelligence information the the Allies. Once communication was established with these groups the NEI intelligence service (NEFIS) took control over these units. While the majority of the guerrilla missions ended in disaster with heavy losses of life, some were more successful especially those in DNG. A continued problem was the shortage of personnel, proper weapons, transport and communication equipment and even clothes and food. Those employed by NEFIS often had no or little jungle training. The Dutch adamant to show their own war effort in relation to NEI independently from the other Allies – with their own weapons and equipment – furthermore suffered from interoperability with the other Allied Forces.

As communication was poor several units in the more remoter areas where unaware of the surrender to the Japanese. On the other hand as the defeat happened so rapidly several units could not be evacuated in time and they kept on fighting. Over time some were able to escape, others were massacred by the Japanese or taken prisoner by them. Many died in the forced labour camps.

On Borneo some units of Dutch and British soldiers kept on fighting till August 1942, more than 6 months after the capitulation. In the end they were massacred by the Japanese.

With the collapse of ABDA the British and Americans – who were in control of the resources – withdrew and refused/were unable to assist in evacuating some 8,000 KNIL troops scattered over Sumatra. These troops destructed most of the oil refineries, that was done so thoroughly that it took the Japanese till 1944 to get them working again at least at some level of production.

The KNIL troops on Timor were able to continue a guerrilla war and was instrumental in tying Japanese troops down which hampered their expansion further into the Pacific. In order to ignore the official order to surrender, the Dutch forces here crossed over into Portuguese Timor. They combined forces with the Australian troops (Sparrow Force) and together decided to continue the fight. After an early chaotic situation they received the support General MacArthur to fight on now as an official Allied Sparrow Force. The Dutch and Australians exchanged liaison persons to better coordinate their actions. A major stumbling block was the very poor state of the KNIL Force, many lacked boots let alone proper weaponry. It took some time to rectify this situation with supplies arriving from Darwin.

While the Japanese received the support from the mainly Muslim population of Dutch Timer, the mainly catholic people of Portuguese Timor assisted the Allied Forces. So after their attacks on the Japanese in Dutch Timor, they were able to retreat to Portuguese Timor with the support of the local population. The Force was also able to relay critical intelligence information back to MacArthur’s HQ at Camp Columbia. As it was difficult to differentiate between the native Dutch and Portuguese Timorese it was decided to equip the Dutch Allied Force (including their Portuguese fighters) with US helmets and uniforms.

With a much more superior Japanese Force MacArthur ordered the evacuation of the Allied troops on Timor which happened in stages between November 1942 and January 1943. Some of the KNIL forces wanted to continue, but when the supplies they requested were denied they had to leave as well. After this NEIFIS continued undercover actions into Timor but as the previous guerrilla activities the casualties were enormous.

An official Dutch account of this campaign published in 1945, claimed that:

Internationally the Timor campaign brought together for the first time, Australians, Dutch and Indonesians. Fighting in small numbers and facing the same dangers, they realised the natural closeness which binds the Dutch Indies Archipelago with the fifth continent…In their subconscious, the image of the Pacific world, carried by positive uniting of the different democracies grew. (Source: Australia and the Netherlands East Indies relations during World War Two, details this operation further. By Dr. Jack Ford)

[1] They included: Both, Reijnst, Van der Lijn, Sloet van de Beele, Van Swoll, and Reael and the British flagged ship Taishan