Herman’s misery that started in Vught and Utrecht, was not over. It all started very positively, a second court hearing followed on 14 January 1944, before the Obergericht in The Hague and Herman was dismissed from all legal proceedings.

But soon after, the rumors of a new arrest started to go around and the mayor of Ootmarsum did again everything he could to prevent another arrest. It was my father’s clear understanding that the mayor of Oldenzaal Weusting was behind this. The latter was not happy that Herman was released without getting any information regarding the local resistance activities.

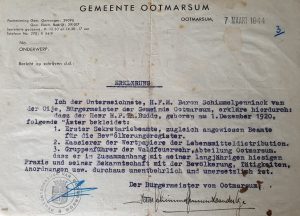

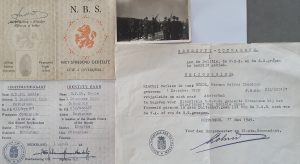

Again the mayor of Ootmarsum tried to intervene. In Herman’s archives there is a declaration of indispensability from the mayor.

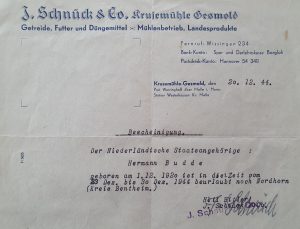

Erklärung 7 March 1944 (archive number 28)

I, H.F.M. Baron Schimmelpenninck van der Oije, Mayor of the Municipality of Ootmarsum, hereby declare:

Mr. H.P.Th. Budde, born on December 1, 1920, holds the following “offices”:

- First secretarial officer, at the same time instructed officials for the population registers.

- Cashier of food distribution securities.

- Gruppenführer der Waldfeuerwehr, Abteiling Ootmarsum (bushfire brigade).

In connection with his many years of local practice and his acquaintance with the population, activities, orders, etc., he is indispensable and irreplaceable.

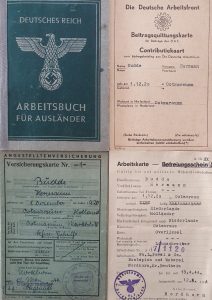

The family envisaged that the next step could be deportation to Germany as a forced labourer. This would be organised by the German organisation Arbeitsfront. With the war going on longer than planned the Germans had to employ more men in the army and this resulted in a shortage of labour. Since 1942 the Nazi forced men in the occupied countries to work in Germany.

Arbeitsfront and Arbeitseinsatz

This was the labour organisation under the Nazi Party which replaced the various independent trade unions in Germany. This organisation also took charge to employ those condemned to forced labour (Arbeitseinsatz). Most large factories in Germany profited greatly from this slave labour and this led after the war to long court cases regarding compensation claims (In the 1960s my dad also received compensation for his time in prison and for his forced labour). In general the German rule was that you could ‘voluntarily’ look for your own employment in Germany, otherwise the Arbeitsfront would place you. People who lived close to the German border often had contacts they could use. They could easily travel home or even travel between their home in the Netherlands and their work in Germany. Other Dutch people that were transported didn’t of course such an advantage and were often placed deep into Germany. They also often were put in labour camps with minimum nutritional food and cramped lodging facilities, they basically were treated as prisoners. Arbeitseinsatz was not restricted to the industry sector and to arms factories; it also took place, for example, in the farming sector, community services, and even in the churches. |

Doing this ‘voluntarily’ this avoided them from being taken in the razzias. These were roundups by the Gestapo (German police) where people were taken from their houses. This could be targeted to certain ethnic groups (eg Jews) but often also involved the random capture of young men to be send to Germany as forced labour, they often got employed by large companies working for the war machine. To ensure operational success, the Gestapo relied on the element of surprise to reduce the risk of evasion as much as possible. So these razzias were very much feared by Dutch people (and of course elsewhere).

As the situation in Germany got worse more pressure was put on the Arbeidseinsatz. Therefore, in the Budde family, his brother Bob got work as a manger on a farm just over the border at Ootmarsum. One of his other brothers Theo jr. got a job with a watchmaker in Uelsen, the owner was also the mayor of the town. His father also being a watchmaker, most certainly used his contacts to get Theo employed here. Herman was in a different situation as he was arrested and sentenced to forced labour.

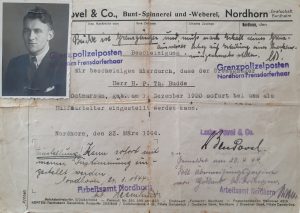

He apparently didn’t trust on a positive outcome of the request of the mayor for him to stay and work at the council. The fact that there is a letter of appointment the Povel textile factory in Nordhorn, Germany – offering Herman a job, three weeks before his arrest– is indication that he started some preparations in case an arrest was inevitable.

Nordhorn was only 12 kms from Ootmarsum by getting him there, just over the border, this could perhaps avoid arrest and it would give him the opportunity to stay in touch with the family.

Herman’s grandfather Gerhard came from this town (he had moved to Ootmarsum in 1871). There were family members living in Nordhorn, so that connection will have been used. See family history Nordhorn.

The attempts to stop arrest were to no avail and by order of the NSB mayor Antoon Weustink of Oldenzaal, Herman was detained for the 2nd time in the night of 14 to 15 April 1944. This was the same Weustink who signed Herman’s appointment letter in 1936 – at that time he was the town clerk of Ootmarsum.

Report on the arrest of Herman dated 15-4-1944

| There is a report of his arrest, which took place between 22:30 and 01:00 hours. it was written by F.W. Heideman, commander of the office of Landwacht Nederland in Oldenzaal. They had received the order from the office in Arnhem to arrest my father. They were informed that he could be in the possession of a weapon.

Their local commander Kip was in charge, but he had first to secure the house with his group of NSB members. During this activity, one of the Landwacht members accidentally discharged his gun and slightly injured one of the others. The arrest itself happened without incidents. However – and this further shows the level of amateurism of the NSB – when they brought their prisoner to the station of the national police in town (Marechaussee), despite making significant noise, they didn’t open their doors. Herman suggested they go to the Town Hall as there would be somebody there. When they knocked on the door and recognised the voice of Herman they opened the door. Later that night Herman was transported to the police prison Oldenzaal. Landwacht Nederland (Land Guard) was a paramilitary self-defense organisation set up by the occupying force which assisted them to “control” the population, which was expressed in acts of terror against civilians, they consisted of NSB members. |

In Oldenzaal it became clear to him what he already suspected during previous interrogations: he was alleged being a member of a resistance organisation. It turned out that the Germans were aware that active resistance was being carried out in Ootmarsum or the immediate vicinity, which they could not get a grip on.

Through Herman they tried to find out more about that group. The “sabotage” of the handing in of radio sets had only been a reason to arrest him.

But whatever the Germans asked for and whatever methods they used; the interrogations did not yield the result they wanted. During the research for my book I tried to find out whether there was an organised resistance group or resistance activities during the war years around Ootmarsum, but as far as is known this was indeed not the case. The resistance took place through individual actions.

The outcome of the trial was already predetermined: guilty. It looks like that he couldn’t be send to a prison again as he was officially released. Perhaps the only alternative Weustink had was to get Herman sentenced to forced labour in Germany. However, he was told that he should call himself lucky that he would not be taken to concentration camp Amersfoort.

He was given the qualification “dangerous to the state” and had to leave the country immediately.

Herman on transport to Germany

What exactly happened is somewhat unclear. On 17 April Herman was put on transport to Germany, he had to report to the labour office in Bielefeld. In the meantime however, it looks like he indeed was employed as a forced labourer at the payroll administration at the Povel factory in Nordhorn. There were cousins living in Nordhorn and one of them worked at Povel but I didn’t come across anything that shows that Herman was staying with them, however most likely that would have been the case.

It is unclear why he had the leave Povel but it looks like that the Arbeitsfront wanted him to be employed in Melle 100 kms further to the east. It also looks like he had to apply for a job himself. The miller’s company J.Schnuck & Co in Krusemuhle-Gesmold (near Melle) had apparently a vacancy so he went there. He seem to have some trouble to convince the manager that he could do the job, in any case by mid June he was employed there. He was rather impressed by the operation.

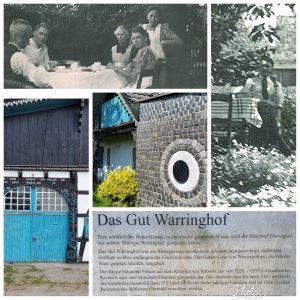

It was a watermill driven by a waterfall, it would have driven the machinery but there must also have been some other machinery as Herman talks about a tall factory chimney. He had found accommodation nearby in Gasthaus Schimm, Warringhoff 31 in Uedinghausen.

Herman enjoyed a considerable amount of freedom there, but was not allowed to go to the Netherlands, without a permit. To occasionally get in touch with his family, he sometimes went by train and bike to the border and there his family was waiting for him. These ‘visits’ were often arranged through Herman’s friend Henny Hulshof.

In correspondence with his brother Theo he also writes: “I won’t be there with your birthday that is now the 2nd time, however this time under totally different circumstances as he was last year. However, there is not a day that I am not thinking of that, but finally that is now in the past“. This is one of the few times that we get a glimpse of his personal feelings about that period. He also writes that if needed he has a job for his friend Henny at the local shoemaker, adding: “it would be good to have him here“.

In the correspondence with Theo it is also clear that he is in contact with his family in Ootmarsum and he send several time sausages to Theo for the family at home. On 3-7-1944 he also writes that he received his first wages DM50 for the month of June. Also in Theo’s correspondence it is clear that there is regular contact with the Budde family in Nordhorn, who is also keen to assist Theo while he is sick. Herman seems to be able to get foodstuff as he also send some to ‘uncle Johann in Nordhorn”. Also interesting to read in the correspondence from Johann Budde to Theo where he writes that their daughters are going on holiday to the Bodensee in Switserland, if there is a war going you wouldn’t know it from the family correspondence that is going backwards and forwards. In the correspondence between friends who are working in Germany under the Arbeitsinsatz , it is remarkable to read that they openly write things like ‘ Out with the NSB’, Long live Holland’. they mock Hitler and talk about free Netherlands and things that are going to do after the war. The mail within Germany doesn’t seem to be censored. In that correspondence they also talk bombardments on Germany, the deafening noise of anti-aircraft guns. Correspondence from the Netherlands talks about a shortage of fuel. So all clear signs that the war situation is changing. Contrasting with the salutary ‘Heil Hitler’ from the official German certificate below.

At the birthday of Theo Budde sr. On the 28th of August 1944 all the family travelled to the border where they met Herman who had travelled by train and bicycle. Theo jr couldn’t make it as he lay ill in the hospital in Melle (Evangelisch Krankenhaus). Herman was also able to once or perhaps a few times visit his younger brother. There certainly was communication between the two of them while they both were in Germany.

Again, it is interesting to see the two sides of this war in the border region where many people would know each other across the border. There is friendly correspondence between the watchmaker in Uelsen (J. Dijk) and Theo sr. regarding the illness of Theo jr. and the care he gets from this German family. Theo and Herman also had regular contact with their relatives in Nordhorn (Gerard Budde) and I am sure they would have helped wherever they could.

Herman also never failed to tell us that he was treated well by the local Germans where he had to work. Those people might have supported or were forced to support the Nazi regime but in the end, they were still decent people.

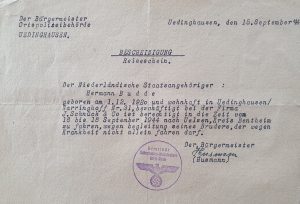

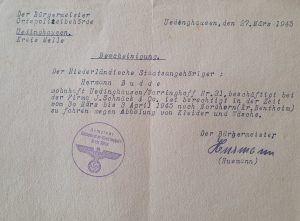

In 1945 Herman took advantage of the chaotic conditions in Germany. He got permission (document on the left) on 30 March to travel to Nordhorn, to pick up clothes and washing, he had to be back on 3 April. However from Nordhorn he fled to the Netherlands.

In 1945 Herman took advantage of the chaotic conditions in Germany. He got permission (document on the left) on 30 March to travel to Nordhorn, to pick up clothes and washing, he had to be back on 3 April. However from Nordhorn he fled to the Netherlands.

At a later stage, he learned that he had narrowly escaped death. It had initially been the intention to send him to the Bergen Belsen concentration camp; that plan had not gone through at the last minute.

In her diary, Anny follows these events on April 27 and May 8, 1944.

When Herman came back to Ootmarsum he immediately joined the NBS (Dutch Domestic Armed Forces) as one of their local leaders. He received his identity card number P.B.032/000187 on April 1st. Interestingly this showed that already well before the liberation the various levels of government in the Netherlands had started their preparations for the situation after liberation.

In the next chapter Anny describes in her diary how the liberation of Ootmarsum happened.

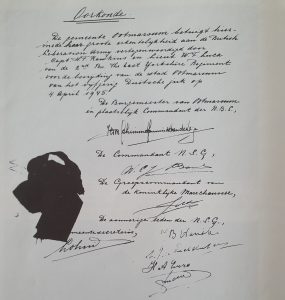

Charter (to the right)

The municipality of Ootmarsum hereby expresses its great gratitude to the British Liberation Army represented by Captain H.F. Rawkins and Lieutenant W.F. Luca of the 2nd Battalion East Yorkshire Regiment for the liberation of the city of Ootmarsum of the five year German yoke, on 4 April 1945.

Signed by the Mayor, the commander of the NBS Combat Unit, the commander of the national police, the town clerk and four members of the combat unit, the bottom one being from Herman.

Nederlandse Binnenlandse Strijdkrachten – NBS

(Not be confused with the NSB collaborators). NBS translates into Dutch Domestic Armed Forces. Officially established on September 5, 1944, to bundle the hitherto little cooperating resistance groups in the Netherlands. They were divided into stoottroepen (infantry) and guards. In the still occupied part of the Netherlands, the Stoottroepen were referred to as ‘Strijdend Gedeelte (SG) – combat unit – of the NBS. Men joining the Stoottroepen had to come from the armed resistance. They were not allowed to appear in public until the liberation. They became the local police and military force before the proper authorities were reinstated. |

On 2 November he received from Mayor Schimmelpennick van der Oyen a bronze grenade shell engraved with all the key dates of his war history. My mum had it regularly polished and by the time I received it, much of the information had been rubbed out.

As Louise and I thought it important to keep this history alive for our children and grandchildren we went to Duncan Vickers a hand engraver in Brisbane. He had to retrace all of the nearly impossible to see text and images , an extra difficulty for him of course was that the text was in Dutch. I also told him the story and he indicated he could this and quoted $400, we thought it important enough to spend that money. When it was ready, he called me to pick it up and he had two small things he couldn’t read. He again wanted me to tell the story while he fixed it. He mentioned that he felt very honoured to be asked to do this work and told me that he did not wanted to be paid for it. I was totally taken aback by this.

So Herman’s story continues………..