Synopsis

My mum and dad were not married or dating at that time. They both worked at the administration of the local council in Ootmarsum.

At the age of 18, Herman was conscripted in the army during the mobilisation of the Netherlands in 1939. After the German invasion he went back to Ootmarsum.

In 1942 he gets arrested because he destroyed posters of the party that collaborated with the Nazis (the NSB). However, he only gets a warning,

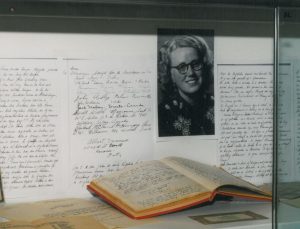

In that same year Anny (at the age of 17) starts with her war diary as it has become clear that the war is here to stay, and she want to make a record for the future. Together with her father they listen to Radio Oranje from London and she passes the news on to the mayor of the town. Writing a diary, having a radio, and listening to it are all illegal activities under occupation, so she and her family are taking serious risks.

In 1943 Herman intercepts secret information that the Germans will confiscate all radios. He contacted a dealer in a nearby town warning him to hide the books that registers radio owners. He is dubbed in, arrested, and send to the concentration camp in Vught. After a few months he is transported to the prison in Utrecht (the worse part of his life). He gets released later that year, but a few months later, in early 1944, again arrested, accused of being part of a resistance group. He is deported to Germany as a forced labourer. He escapes towards the end of the war and takes part in the liberation of Ootmarsum as a member of the combat unit of the Dutch Domestic Armed Forces.

European wars

| The big European wars during the 1900s are all related. Ever since what became German, won the Prussian-French war of 1870/1871 in which my great-grandfather fought there was a power struggle the upcoming power Germany and the other well-established major European powers. They didn’t really want to provide an equal place to Germany in their dealings with each other, and this became a key trigger for the First World War. Germany was heavily punished for the war at the Treaty of Versailles and in the following years its economy collapsed. This opened the way for a populist leader and Hitler happily took that role.

This led to the WWII (1940-1945), after this war ended lessons were learned and massive loans were provided by the USA to build up the whole of Europe, including defeated Germany. However, deep divisive lines had already started to emerge between the war allies, with western democracies on the one side and communist Russia and its occupied East European States on the other side, as no weapons were used this was called the Cold War. This ended with the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and the collapse of the Soviet Union. For the next couple of decades there was a real détente. This started to change again two decades later when Russia, China and America became involved in a new round of power competition, it is still unclear where this will lead to, but is certainly something next generations will have to deal with. |

Today’s relevance of Herman and Anny’s acts of resistance

Only when others start talking about their experiences of what a war situation means – not so much the fighting, but the occupation by a foreign enemy – can you start to comprehend the stories that you have heard from your parents who went through a war. It then becomes possible to better appreciate their stories, information, and emotional reactions. It also becomes clear why so many ordinary people who went through war and occupation are saying, keep the story alive. Freedom is not a given, you must work hard for it. It is very easy to slip into geo-political situations where war seems to be inevitable. Looking back at history war was in general the norm with peace the exception. This is very hard to understand for the current generation, who have never experienced war, nor their parents. Add to this the lucky country of modern Australia that have hardly seen an occupation.

I do however want to pay my respect to the Aboriginal people of Australia who were occupied by the colonial forces. They most certainly did fight for their freedom and for the unjust that was done to them, for them there most certainly a war raging against them. The Aboriginal people are still paying the price for this.

We humans seem to be a very warlike specie, constantly negotiating between competition (ego/self) and collaboration (social).

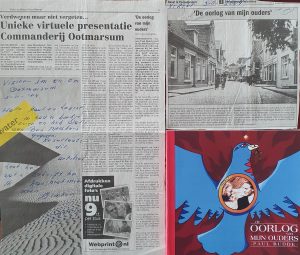

Back to WWII. When public attention is shone on your mother in two books and an exhibition, you realise that there were not all that many others who also kept a war diary, which of course was forbidden by the occupying force. When you hear that in the Netherlands, especially in the first years of the war, there was very little resistance and that your father was arrested for the first time in 1942 for resistance activities, you know that he is an exception and not part of the norm. He was literally risking his life for freedom. Also nowadays the majority of the people won’t necessarily stand up against injustice, so Herman and Anny providing an example here.

When you then realise that both your father and your mother, completely independently of each other, both played an important role during the war each in their own way, then it slowly begins to dawn on you that this is something unique.

During all these years, the main ingredients for the book that I have written on their war activities was all the time there for me to research. My mother’s war diary and my father’s war archive where very well known to me. However, it took many years for me to realise the significance of it. This spurred me to capture this unique history. I published the book in Dutch in 2004.

As a 17-year-old, my mum captured both her own local experiences as well as the broader international picture in her diary. She writes about how the occupation affects her life and that of the local community, in her town Ootmarsum, close to the German border. (While Ootmarsum

She was in a good position as she worked at the town hall where the mayor was clearly anti-Nazi, but where there were also collaborators. So you always had to watch over your back. At the same time she illegally listened to the radio which they had hidden in the carpentry workshop of her father. If she would have been caught or if somebody would had dubbed her in that could have resulted in her being arrested and send to one of the notorious concentration camps of the Nazis.

My father – who also worked at the local town hall – took a more active role in the resistance, for which – as we will see – he paid dearly. After the war, he has never able to talk about the war. I think he was afraid that this would stir up memories. I guess that he most probably was frightened that this would lead to emotional reactions he could not control. Both he as the person he was and the time in which he lived after the war (he died in 1977) were not very conducive for such confrontation. Interestingly social analysts have discussed this phenomenon. They concluded that there were several reasons for this. There were always people that were worse off than you, so who was interested in your story. There also was shame among people he didn’t stand up, who stayed silent or even openly or separately collaborated with the enemy and therefore avoided any discussion. Furthermore the country lay in shatters and there was a need to move on and start working on the recovery, the focus was clearly on the future, not the past.

It was only in the 1980s and 1990s that the time was right and society began to show interest in the stories of these people. My dad has always much preferred to keep emotions to himself, which makes the poems he wrote at the age of 21 even more remarkable. He clearly died too soon for him to be able ‘to come out’ and talk about it.

My mum and dad were not dating during the war years, they obviously knew each other. My dad was dating another woman. My mum was four years younger and had a different circle of friends. They were not aware of each other’s illegal activities, until of course my dad got arrested.

The most interesting entries in my mum’s diary are her personal experiences and emotions on which she reflects in-between the myriad of world-wide events. With jubilation she reports on every advance of the Allies and on the defeats of the enemy.

I have not been able to find anything in their youth from which one could conclude that their war activities were a clear consequence of what they did in their teens or that their parents were an important driver in this. Perhaps just the opposite. Nevertheless the activities they undertook were very dangerous and could have fatal consequences.

And after the war, they were just the same people as before the war, just like most of the other people around them. But in that Second World War, they both did something exceptional — something most of the others around them didn’t do. Very consciously, they both went into a territory that they both knew were putting their lives as well as those of their relatives at risk. But their inner desire for freedom and justice was clearly greater than fear. Did the world change because of their activities, of course not. But they kept the spark alive; that it is worth to stand up against unjust and the forceful taking away of liberty. I am very proud of them as they – within their own capacities – stood up. This is an example for all of us and their activities are as important for us today. Their resistance is an example for us to ensure that we also stand up against injustice and against activities that undermine our democracy and our liberty and that of others.

I can strongly relate to this, and it is with that inner feeling that I started to research this history. Apart from the diary and dad’s archive I did find interesting documents in the Dutch War Archives and that of the Red Cross, the latter tried to aid those imprisoned by the Nazis, including getting parcels from his family to my father.

I published the book in 2004. Nothing of course has changed to the content of that book since that time, however the world around us has changed since that time. Nationalism, populism, fake news, political lies and an undermining of democracy and its institutions have taken hold in many countries in the western world.

Therefor the importance of this book is now even more significant than at the time I did my research for it. It shows what can happen to ordinary people who simply want to go on with their lives when totalitarian regimes are allowed to rule –as in the case of WWII – which led to unthinkable suffering of hundreds of millions of people. These regimes don’t appear out of thin air, they grow, often supported by large parts of the community – even the majority. There are similar signs in the world around us, nowhere near as bad as for example what happened in the 1930s, but nevertheless there are warning signs. We do have the knowledge what can go wrong and therefor have the responsibility to stand up against injustice and the undermining of democracy. We have the power to do so but we need to act, it doesn’t happen automatically.

Seeing my grandchildren growing up and seeing the geo-political changes that are happening prompted me to start translating the main parts of the book as it is important that my children and in particular my grandchildren have access to this information so they in turn can learn from the lessons from their great-grandparents and pass the message on.

I have not translated all the entries my mum wrote in her diary and not all the archived documents from my father. If further interest is sparked by it, Google Translate can further assist them.

Paul Budde, 2021