My parents were both born in the twenties of the 20th century. These were prosperous years and a direct reaction to the First World War (1914-1918). The Netherlands had not suffered from that war. It was in the interest of both Germany and England that the Netherlands remained neutral so that happened, the Netherlands did not yet have a real opinion of its own at that time. It had seen economic decline since the collapse of the VOC (Est Indies Company) in the late 18th century and had largely stayed in the doldrums since that time.

WWI, died, without a direct result when many of the troops start walking home on their own accord. That is, the soldiers who survived; 8 million young men were killed and 23 million were wounded.

The First World War is unique in many ways, but one of the most frightening points was that the start of the war was inevitable even before it had begun. Countries like Germany were out to prove their strength and were ready to take their place in history. The country as such only existed, since unification, in 1871. England, the world power before the war, was only too happy to teach a lesson to the new economic enemy. These countries, in their enthusiasm, sucked the young men from their colonies with them. And singing, the troops marched up to the battlefields encouraged and waved on by relatives and compatriots. It was a party, an honor to be able to do that for ‘The Empire’ for ‘Der Kaiser’ or for the Tsar. Names and dates of birth were falsified to be allowed to participate.

Once arrived on the battlefields of Belgium, Poland, Turkey and North Africa, the reality turned out to be very different, that is, for the troops. The army leadership pretended that nothing was wrong and played its strategic games from the command posts, like others play a board game. Stuck in their old aristocratic military traditions, without any regard for a totally new way of warfare.

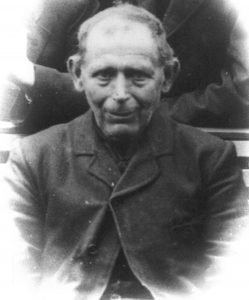

The feudal era that had defined life in the countryside for some thousand years came to an end in the first half of the 19th century. Since 1848, the first democratisation processes had made a considerable advance and there was a constant opposition to the rulers that consisted exclusively of the established aristocratic order. 1848 was also the year in which my great-grandfather, Gerhard Budde, was born.

In most European countries there was a revolution that year that led to new constitutions, the creation of Parliaments and the impetus for more participation for the rest of the population. Between 1848 and 1870, the authority was converted from the king to parliament, initially leading to a liberal policy, with economic freedom. The aristocracy moved on to liberal politics and made a new alliance of power with the wealthy businessmen. It was the latter group that benefited most from the new democracy. It was not until after the Second World War that there was a real democratic breakthrough for the benefit of the entire population.

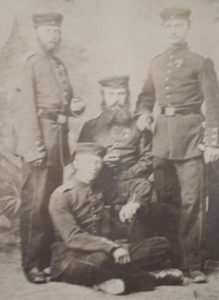

But in 1914, the kings, emperors, admirals and colonels hung on to their traditional personal power with their last fingertips, and they saw this war as a new opportunity to strengthen this power. With that illusion in mind, they wanted to wage this war oh so badly and the propaganda machine had made everyone enthusiastic. The social class difference, which had been the order of the day for more than a thousand years, found its continuation in the relations between the (aristocratic) army leadership and the men. The soldiers could thus be used very easily and without any problems by the elite as cannon fodder. They still thought of the battles and wars that came to an end in weeks and months, such as the last European war between France and Germany of 1870/1871 in which Gerhard Budde (Der Altkrieger) had also fought.

Sunday, August 28, 1916

| On the day my great grandfather – der Altkrieger – died, 28 August 1916, there were artillery activities at the front near the Somme. The French gained ground southeast of Thiaumont and repulsed attacks from the Germans at Fleury and at a position near Vaux Fort (Verdun) |

When the men began to experience the reality of the trench war themselves, they could not go back, they had no control over what and where something happened. Desertion often meant execution on the spot. That also led to a certain degree of fraternisation between the enemy forces. There are plenty of stories where these men went to visit each other in the trench between battles, exchanged food and cigarettes, sang Christmas carols together, etc.

The battlegrounds were very concentrated, and no one made progress. There was no real end to the war with capitulation signatures, etc. The Russian soldiers had already mad up their mind in 1917 and walked back to Moscow, where they killed the Tsar a year later. Following in the footsteps of the Russians, the German and Austrian men also turned around in October 1918 and began to walk back home. With 8 million dead, a third to half of all young men in the war-waging countries did not return.

The retreat was not led by the old elite, who had glorified the start of the war with so much propaganda to heroism, but by the disillusioned soldiers who once returned to their country set up soldiers’ councils to prevent them from being sent back to such a horror. The example of this came from Russia where such councils had existed since 1918. In the house of the Buddes in Nordhorn, a similar ‘Soldier Rat’ (Soldiers Council) was set up in 1919. Eventually, the era, which had begun around 1848, ended with the collapse of the old authority structures in Germany, Austria and Russia. England also lost its world power position; America took over this position. This was confirmed during the disastrous treaty of Versailles signed in 1919. It was clear from the outset that Germany would never be able to pay the reparations, and this laid the foundations for great poverty and dissatisfaction. While the new power structures in the surrounding countries were more moderate, the new structures in Germany were much more extreme.

With almost 70 million men under arms, during the First World War, it came down to the women to keep the economies going and to provide the troops with weapons, food, clothes and other supplies. While the men had slowly but surely become more emancipated during the previous 50 years, the women were still mostly locked up in Victorian structures. There were strict rules for everything: the length of the hair, the length of the skirts, the layers of underwear, going out without a chaperone was still taboo, girl-education was far behind that of the boys, working outside the home was almost impossible and so on. They, like many other civilians in 1918, were hit by the Spanish flu, in which 50 million people died and that also led to major stagnations in the war industry.

After the women had kept the economy running, there was of course no turning back for them after the war. Women’s suffrage now became general, education was tackled, and with more self-awareness, ‘fashion’ made a broader appearance.

Combine the disillusioned soldiers with the ‘new’ women and you have the twenties. Old traditions, kept alive by the same elite who had led them into the war, were thrown overboard and a whole new social structure began to develop, especially in Germany and France.

The Netherlands had not experienced all this so directly. Life had taken its course and the old guard thought they were going on in the same way, as they had done for one during the war. Equality between women continued to lag behind and working outside the home only started in the Netherlands in the 60s and 70s of the 20th century.

The certainty of faith

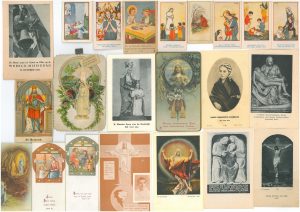

My parents grew up during the heyday of what was known in the Netherlands as the ‘Rich Roman Catholic Life’, expressing the outpouring of catholic traditions after this religion was again allowed to be practices since the mid-1800s. With this freedom of religion, new forms of communication, prosperity and education were all important means that made it possible for the churches to exert a more direct influence on the believing souls. Ootmarsum was predominantly Roman Catholic. The dominant religion in the Netherlands since it declared itself independent from Spain in 1588 was Protestantism (Calvinism).

The Dutch society in these times was well known for its silos. Protestants, Catholics, Socialists, Liberals.

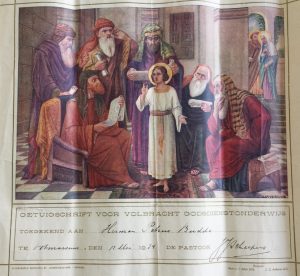

Life took place within your own silo among your fellow believers. This applied to schools, singing societies, theatre performances, insurance, outings, etc. You bought from fellow believers, married fellow believers, went to coffee together, went on holiday with each other, etc. You learned Catholic history, learned the Dutch language from Catholic language books. Every day had its own Saint, every season its rituals. In the heydays of the church, you knew exactly what to do, what prayer was part of it and what action was expected of you. You could spend days looking forward to the splendor that Easter or Christmas brought with it, to the water that was consecrated at Candlemas, to the candle blessing of Blasius. In the days before Pentecost there were the thunder sermons and the tension was felt in society; earn indulgences with All Souls’ Day, and so on. Life was ordered with the right dosages for love and suffering, penance and joy, tension and tranquility, the pillar in which you sat with your ilk ensured that these relationships remained as neat as possible. This silo structured survived two world wars but eventually collapsed during the 60s.

The activities within these silos were most likely more important things for my parents’ parents than the fighting during the First World War, which took place a few hundred kilometers away in Belgium. Like most Dutch people, their lives also took place within their own silo and what took place outside of it came in second or third place.

At the head of the silos were the bishops, cardinals, pastors, pastors, pastors, politicians, trade union leaders and together they were in control and cooked up the political course of events in The Hague. They knew what was good for you and everything within the silo was aimed at confirming that, and people believed that without asking too many questions. What those leaders decided was good for you. Not that they weren’t complaining at the time, but when it came down to it, the ordinary citizens still didn’t have much to say at the time. Outside the top, there was virtually no contact with people in the other silos. Each

silo had its own truth. This truth came to you through the Catholic school, the Protestant pulpit, the trade union newspaper, the Reformed radio and so on. The leaders of the silos were closer to the old aristocratic elite of the 19th century who were on their last legs, than to their own members. The exceptions here were the socialists, but here too the activities took place strictly within the own trade union silo.

Problems outside of everyday life weren’t too many. It was left to the church and political leaders. The silo provided all the security needed to go through life. External conformation with the silo was of utmost importance, at least once a week (Sunday) to church in a neat suit or dress and with a serious face. You didn’t have to think, the rules were known and weren’t questioned. The main issues discussed at the local level often concerned persons who violated the written and unwritten rules of conduct and, for example, did not behave correctly in the church (e.g. sitting down before the sermon was not possible, talking and laughing was taboo, clothing and layout was another popular topic, certainly about the women, too free contact between boys and girls, going out outside the ecclesiastical associations was taboo, and so on). Often these ‘issues’ were dealt with again in the pulpit, whether in veiled terms. There certainly won’t have been too much attention paid to World War I from the pulpit, because those were issues for the leaders not for the good believers. The emphasis here was on hell and damnation if you violated the rules of the silo. There was no room for discussion or flexibility, you do what the pastor or the pastor says, off!

The hell alternative was very shocking, but with much prayer, repentance, penance and good intentions, there was always hope in heaven. No one knew exactly what that meant, but there was no one really worried about it – it was just certain.

Everything in the column was attuned to this pattern of life, which was extensively confirmed at school, in the newspaper, on the radio and so on. It was clear how you had to live and most of them never thought about it. If you kept to the rules, you didn’t have to deal with anything. You therefore had to pay much less, and you could therefore fully enjoy the fringes of the column. Processions, banners, drums, high masses, choirs, manifestations and so on. Within the silo, everyone was also clearly listed. At the front of the church were the notables, the seats in the front were higher and/or more decorated than in the back, there you could see neither the altar nor the pulpit.

Quantity was important, quality did not count praying a lot, often going to church, knowing all the words of the catechism was an achievement. In the 50’s I almost always managed to get full marks for catechism. When I read the catechism again now, 40 years later, I still don’t understand the content, but doing it at that time was not a problem for me. Unfortunately, the Catholic reputation had already dropped quite a bit when I reached my teens, and I didn’t get much praise for those high marks anymore. However, had I lived 50 years earlier, I am sure that with those high marks I would have achieved honor and reputation among the fellow believers in my Catholic silo.

Both my father’s parents and my mother’s parents were faithful members of their column, the Roman Catholic Church. Probably my father’s father must have been the weakest link, because stories regularly pop up about his lively life, and it is certain that he regularly lived on the edge of the rules with his loyal comrades. One of his friends is sometimes only spoken of in a whisper! But also certain is that he never really went much further than the edge, as he came from a too solid Catholic family.

My father’s parents had met through the Catholic singing associations, she in Oldenzaal, he in Ootmarsum. They were married on January 22, 1918.

January 22, 1918

| On the day my father’s parents got married there were German attacks at St.Quentin and La Bassee. The English carried out heavy bombing raids at Roules, Menin and Courtrai. |

From several songs that were written on the marriage of Theo and Marie Budde and on the occasion of the 25th wedding anniversary in 1943, I have been able to conclude that Theo was called up for military service during the First World War and was stationed in Amersfoort. But after only eleven days he was dismissed but needed to remain on standby. I was also able to make out that Marie did want to go to the Netherlands East Indies, but that eventually did not take place. Theo’s best friend, Leo Brons with whom he had started the military service, was sent to the Netherlands East Indies.

On the faith side, I only knew real piety from my mother’s father. When he came to visit us in the 60’s he often sat in front of the TV watching church broadcasts and when the pope appeared, signs of the cross were made and his eyes sparkled. Walking next to him through the streets around our house, he could stop by a beautiful chestnut tree in bloom and say, ‘how beautiful God’s creation is’. I was the first to find him dead in his bed in the morning, he peacefully died in our home. When I close my eyes, I can still see him lying down: hands folded with the rosary between his fingers, quiet facial expression, quietly falling asleep and traveling directly to heaven. My mother later told me that he was praying the last ‘tenner’ on the rosary. Looking back, he is for me the window to that ‘Rich Roman Catholic Life’ that provides safety and certainties in life.

At the same time, looking back these silos also had a smothering effect on the development of those within that silo, but whether we are so much happier now I do not know, certainly not when I close my eyes and think of my grandfather.

My mother certainly inherited that strong faith from him and hold on to that till her death in 2018. She had however, no problems adapting to the huge changes that had taken place since her childhood. Her faith was contemporary and based on her own inner beliefs and not on the traditional rules and laws of the Church. I already find the important role of the church in her life in her diary where she talks about Protestants and Jews much less compartmental than what must have been the norm then.

I also did find this an interesting entry in her war diary. On April 22, 1945, she writes: “Today is a general day of prayer for the west. On the radio a beautiful Mass broadcast with preaching that mainly applied to the women and girls who gave themselves away to the soldiers.”

The prosperous twenties

For Anny and Herman, there was a carefree childhood, both of started their school days in this decade.The period is known as the Roaring Twenties. People enjoyed life after WWI

In the Netherlands the industrial revolution started rather late. Germany, France, England and Belgium were all already in full development when the Netherlands only started in earnest after 1870. This was still at a time when there was a clear separation between the state and the economy. Liberal policy was aimed at economic freedom with no state influence whatsoever. This resulted in a great economic revival: railways, telephony, cars, electricity and so on. But the fruits of it were mainly picked by the thin top layer. For the rest of the population, the result was shocking. Working conditions were below par: great wealth at the top and great poverty among the rest of the population. The Dutch King William V tried to hold on to the ‘ancient regime’ and refused a faster democratisation of the country.

If we look back on human evolution, it is interesting to note that the lower layer of the social class evolved from slaves to serfs and from there to factory workers. Fortunately, the percentages have changed in the last 50 years, and today’s factory workers make up a significantly lower percentage of the population.

But the social abuses could no longer be ignored. The social movements also began to gain a foothold in the Netherlands and that caused a great stir within the established parties that were also neatly set up within the silos. In addition to the Liberals and the Conservatives, there were the traditional Protestants (Christian Historical), the Reformed (Antirevolutionary), since 1888 the Social Democratic Alliance (later PvdA) and since 1889 the Roman Catholic State Party (later KVP).

As a result of the school struggle (equalisation of secular and religious schools) of 1878, the Christian parties began to work more closely together and from 1885 to 1925 this cooperation dominated Dutch politics. National insurance, the prohibition of child labour, the right to vote, the school system, working hours are the main results of the state’s influence on social and economic society.

While there was frequent political consultation within the top of the parties and often joint decisions were taken, the (lower) party structures within the silos remained strongly separated, each with its own rigid party programs and strong discipline towards the members.

The political changes, which after the First World War brought about a dramatic change in the political governance of surrounding countries, did not reach the Netherlands. In November 1918 the socialist Troelstra led a badly prepared (political) revolution, which failed (the Troelstra’s Mistake). The idea was based on the revolution in Germany in which the emperor had been deposed a month earlier, which should have led to a ‘real’ parliamentary democracy. The “Troelstra revolution” failed, but it nevertheless led to considerable reforms within the Dutch system: the 8-hour working day was introduced, there was a general national insurance and universal suffrage for men and women.

This period of political upheavals was possible because the old elitist power structures completely collapsed. With more than 30 million European soldiers dead or wounded and a much more empowered female part of the population, a political consciousness had started to set in motion, aimed at ensuring that such an insane war would no longer take place. A more empowered population also led to greater political diversity, no longer based on traditional systems. On the one hand, this resulted in the communist parties that became very strong in Russia, France and Italy, and on the other hand, the Nationalist parties that scored successes, especially in Germany, Italy and Spain.

However, the Dutch silos ensured that these political developments largely passed the Netherlands by.

The lean thirties

For the time being everyone wanted to move forward and the twenties were also full of action in the Netherlands, swinging and prosperous. This ended abruptly in 1929 when the Stock Exchange in New York collapsed that led to the great crisis of the thirties. The Netherlands received more than its share of this for two reasons. The Dutch economy had always been heavily dependent on the German economy. The treaty of Versaille had made Germany poverty-stricken and that also had its influence on the Netherlands. Subsequently, for ten years, an economic mismanagement was conducted by Prime Minister Colijn. Instead of stimulating the economy, he shrank the economy – which led to more unemployment, a reduction in purchasing power: a vicious circle. As a result, more and more Dutch people lost confidence in politics and the anti-democratic movements gained much more support here as well. In 1931, Antoon Mussert founded the National Socialist League, the NSB, which was oh so notorious in the Second World War.

Antoon Mussert

| Antoon Mussert was an engineer at the Provincial Water Board in Utrecht. He founded the NSB in 1931. He was not seen as full-fledged by the Germans, while he did his best to dance to Hitler’s tune. He had no real power despite his title: Leader of the Dutch People.

The anti-democratic German Nazi party eagerly took advantage of the economic malaise. Germany had serious economic problems even before 1929. When Hitler came to power in 1933, he began an economic policy of expansion; the construction of motorways, the construction of a war industry, the car industry (Volkswagen), chemical companies and so on. Furthermore, Hitler refused to continue the reparations and began to reclaim the territories specified by the Treaty of Versailles. The first move was the occupation in 1936 of the Saargebiet that France had claimed in 1919. All this made him very popular among the German population. For most Germans, the thirties were a time of flourishing and a renewed sense of German unity. |

It is also important to mention here that since the unification of Germany in 1871, the country had not known democracy. This came only in 1949 and Germany was therefore one of the last Western countries to receive a democratic system.

During the war, Dutch Prime Minister Colijn was replaced by Arthur Seys Inquart. He had been Chancellor of Austria since he had invited the Germans to take over his country in 1938 (Der Anschluss). From 1940-1945 he was Reich Commissioner for the occupied Netherlands. He started with a moderate policy but was soon very active in the Nazi terror.

This was also a difficult time for the Velthuis and Budde families. Money was scarce and for Anny and Herman meant that every day they had to cycle up and down to the high school in Oldenzaal, taking (the expensive) bus was not on it. They were both still among the lucky exceptions. Most girls were not allowed to continue their studies and boys were often taken out of school early to go to work. Thanks to the mediation of his father, Herman started working as a volunteer at the town hall of Ootmarsum in 1937.