In September 1822, the House of Commons accepted the report tabled by Bigge and Lord Bathurst instructed Governor Brisbane as mentioned above to start investigating the best place for this new penal settlement.

Governor Brisbane had decided that only married officers with families were to be sent as commandants to the outer settlements.

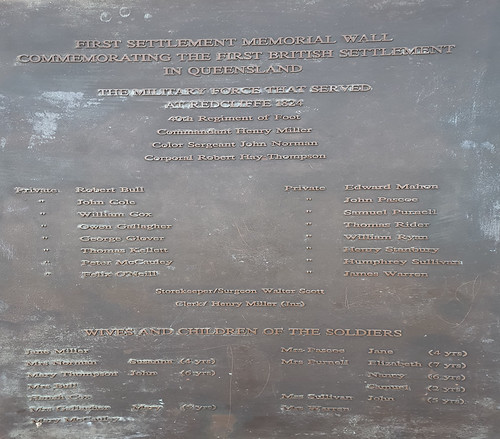

On 12 September 1824 Lieutenant Henry Miller of the 40th Foot Regiment was formally appointed to establish the Moreton Bay. However, Miller had already taken charge of the preparations as he had arrived in Sydney a couple month earlier. During that period, he organised six months of provisions, including sheep, goats, pigs and poultry. They left Sydney on the 29th of August and arrived in Moreton Bay in the brig Amity on the 10th of September.

Brisbane’s instructions to Oxley were as followed: “The spot which you select must contain three hundred acres of arable land and be in the neighbourhood of fresh water. It should lay in the direct course of the mouth of the river, be easily seen from the offing, and of ready access. To difficulty of attack by the natives, it ought to join difficulty of escape for the convicts”.

Brisbane also gave Oxley detailed instruction regarding a survey of the river and its shores and possible establishing its source. So the possibilities of the river were of interest from the very beginnings.

Apart from the military Commander Henry Miller and Surveyor General John Oxley passengers of the Amity included Allan Cunningham, the King’s Botanist, with their respective servants, and Assistant Surveyor Hoddle. Other members of the 21 strong military contingent included Lieutenant Butler who oversaw the small contingent of the 40th Foot Regiment, consisting of a sergeant, a corporal and sixteen privates. Commissariat Storekeeper, Mr. Walter Scott, who was also to act in the capacity of a surgeon, together with an assistant, were also on board. Some of the above-mentioned people also brought their wives and children with them. In all they included 11 women and 8 children.

The twenty-nine convicts who accompanied the expedition were trades people such as carpenters, sawyers and brickmakers as well as other skilled seamen and labourers. Many of the convicts were ‘volunteers’ promised to receive a reduction of their sentence.

It is interesting to see how detailed the instructions from higher hand were. This is what Brisbane instructed to Miller: “not a moment is to be lost in constructing huts for the soldiers and convicts. Those for the troops are to be placed in a commanding situation three hundred yards distant from the huts intended for the others. The former should be enclosed by a strong palisade and ditch to secure them from assaults. As soon as this has been effected a store, a guard house and a goal ought to be erected. Shortly after your disembarkation you are to establish a Signal Station on some height seen from the offing.. . “

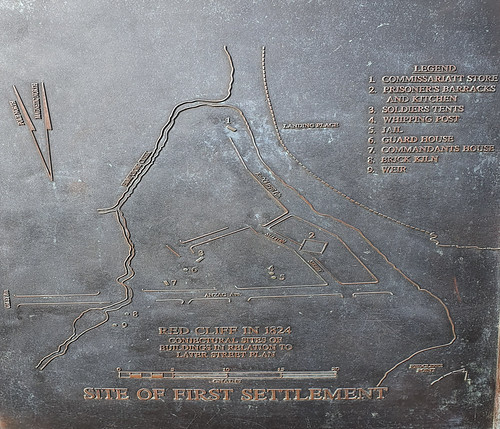

They spend a couple of days looking for the right site, investigated both the islands in the Bay as well the mainland. On the 15th of September they agreed on the site, pegged it out along the Humpybong Creek and started to build a log-walled penitentiary consisting of a guard house, jail, soldiers’ barracks and prisoner’s barracks surrounded by a stockade of timber posts and pickets. There were no buildings, except huts, most people were accommodated in tents. Queensland’s very first map was produced on that day by the surveyor Robert Huddle of the coastline of Moreton Bay around Redcliffe.

The only link to civilisation was the occasional arrival of a ship from Sydney into Moreton Bay.

The plaques below are all at the Settlement Monument in Redcliffe

It was in these surroundings that Miller’s wife Jane gave birth to a son, who was afterwards christened Charles Moreton Miller, the first European child born at Moreton Bay and the first Queenslander.

Communication between the Mother Country – as Governor Brisbane called it – and NSW was often difficult. By now the British Government had decided to reopen Norfolk and to not continue with Moreton Bay. This of course created a problem in Australia. As the ship with the first group had already started building the Moreton Bay Penal Settlement. Governor Brisbane wrote back that the Settlement had already started but that he would visit Moreton Bay and report on its suitability as a penal colony.

However, in the meantime it had become clear that the beach side at Red Cliff Point was unsuitable. There was poor anchorage, little fresh water, many mosquitoes and hostile Aboriginals. It has been argued that the resistance coming from the Aboriginal people was significantly more serious than Miller was prepared to acknowledge.

On November 9th, the Amity left Sydney again bound for Moreton Bay. This time with Governor Brisbane, Oxley and other officials keen to visit the new settlement. Accompanied by John Oxley he also cruised the river to a site 9 to 10 miles from the mouth of the river (Breakfast Creek). Oxley suggested to move the settlement from Red Cliff to this spot on the river, the Governor agreed with that. At time the Red Cliff settlement was formed there was not enough information about the river. This had only become clear after Oxley and Cunningham two week long trip over the river in October. Also at that time the southern entrance to the Bay was unknown, which provides easy access to the river. They stayed overnight on the river before turning back.

Brisbane reported back to London that in his opinion the Moreton Bay Penal Settlement was needed as a penal colony as Port Macquarie was no longer suitable for maintaining convicts as the area was receiving larger numbers of free settlers, which made convicts escapes via the new settlements in the Hunter Valley easier. However, the settlement was agreed to be moved from Red Cliff to the river. He also concluded that Norfolk Island was not suitable for large number of convicts and would be used only for the most hardened criminals.

It looks like London accepted the reality of the Moreton Bay Penal Settlement as there was no further follow up from the British authorities. Separately however, after a ten year hiatus Norfolk Island was reopened again.

When Tom Petrie visited the site in 1861 and showed Patrick Byrnes the kiln. He judged them as being of excellent quality and used some of them to built the chimney of his house in that year. Patrick was the father of Thomas Joseph Byrnes, the progressive and much loved premier of Queensland who – because of his sudden death – was only in office for five month in 1898.

Henry Miller – the real founder of Brisbane

Convict History of Brisbane TOC