At the start of the penal settlement there were now female convicts. However in 1827 three female prisoners had arrived. They were employed in shelling the corn. The number of female prisoners grew and two years later there were 18 women, some of them perhaps wives of the male convicts. Certain classes of male convicts were allowed to bring their wives and children with them.

Finally a female prison (factory) was build in 1829. It was situated near Wheat Creek. It occupied the total block between Edward, Queen, Creek and Elizabeth Street. Between 1832 and 1834 the average number of female prisoners was around 36.

Like the men’s prison, this was for secondary offenders. The majority of women that ended up as convicts followed a common pattern of unwanted pregnancies, desertion by their husbands and unemployment. They ending up on the streets and in order to survive committed petty crimes and offering themselves for prostitution. After obtaining their freedom they often remained marginalised and were forced to return to their street life activities and as such became second offenders and ended up in Moreton Bay. In all some 144 re-convicted women went through this penal settlement.

The Female Factory had only seven rooms and created for a very cramped prison. Like most other buildings in the settlement it had an outside kitchen. The military leaders were anxious to prevent fire in this hot and dry climate.

The work of the women consisted of picking the loose fibres from the ropes for the use of making a sealing that was driven into the wedge-shaped seams between boards of the settlement’s ships to stop them from leaking. They also did needle work, produced rough woven clothing for the male convicts and they did the washing for the men as well.

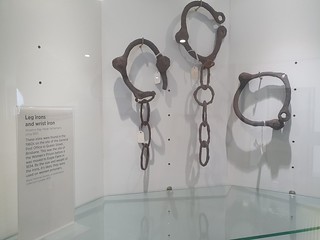

The conditions in the Female Factory were significant worse than that of the male prison. They were more crowded and they had less opportunity to be outside. They were only once a day allowed to walk around outside for some exercise. If they absconded and in particular when they met with soldiers in the bush they were put in irons.

The building was situated on the edge of the convict settlement. For this purpose the women had extended the existing track to Breakfast Creek to the Farm, this basically followed was is now part of Kingsford Smith Drive in Hamilton. A bridge was build over the Creek and soldiers were not allowed to cross the Creek.

The Farm the authorities thought was far enough away to protect the women from sexual harassment. Initially the area was fenced but it soon became clear that this didn’t prevent men (mainly soldiers) from entering the prison. Despite strong regulations to the contrary the military were eager to visit the women. Many of the women were happy to offer their services as prostitutes as this was the only way for them to get some extra food or rum. As a result several children were born and they also stayed in the prison. However, they received schooling with the other children outside the prison.

The female factory provided great stories of intrigue and sex, provided by ‘seducers’ representing all layers of the early Brisbane population. Rather quickly a wall was constructed around the building. However, this did not seem to stem the flood of ‘seducers, who were assisted by the warders and the ladies though liberal ‘tipping’. Regardless of the counter measures, intrigue and disregarding the sexual restraints remained rife. Commander Foster Fyans complained back to the Governor in Sydney that it was more difficult to keep the military under control than the convicts. Soldiers and officers were locked in their barracks at night with iron bars across the doors.

Women caught were put in solitary confinement in tiny cells, put in irons or had their heads shaved.

Men caught illegally entering the female prison include a ship’s captain, the chief constable, the local clerk and the settlement’s first doctor Henry Cowper. This was the the last straw. In 1836 Fyans moved the female prisoners further out to a building in Eagle Farm.

For a while the Female Factory in town was retained for the more hardened female offenders.

According to research conducted by University of Queensland honorary research fellow Dr Jennifer Harrison, during the 1826-1839 period 22 children were born to the Moreton Bay female convicts, where the age of the female inmates ranged from 16 to 80.

The Female Factory was fully vacated in 1837 and all remaining females were now housed at Eagle Farm. Soon after that it became the temporary home of the Petrie family who had just arrived from Sydney and lived here until Andrew Petrie – the newly appointed Superintended of Works – had built his house further up Queen Street on what is now the corner with Wharf Street.

In 1849, after the convict era, the Old Female Factory became the Brisbane Goal and a police court. Male and female prisoners were kept in separate rooms. The site became known as Goal Hill. From here it moved ten years later to Green Hills (Petrie Terrace). A dedicated women’s prison was opened in Fortitude Valley in 1863

Morals and social norms became increasingly more important in the 19th century and policing them became a priority for the authorities. The ideal woman was virtuous, pious, obedient, loving and nurturing. Her place was in the house as a caregiver. Women who stepped outside this ideal concept were seen as offending both against the law and against nature. In most cases women received more severe penalties for similar offences made by men.

The Old Female Factory also functioned as an immigration depot and a fire station. In 1871, the old prison and most of the hill was levelled when the GPO was built, which is now occupying the exact same spot.

Griffith University Visiting Fellow Jan Richardson is researching female convicts and ex-convicts who arrived in Moreton Bay after the closure of the penal settlement in 1839. Her current project comprises a more extensive examination of historical and genealogical records — including photographs, family trees and cemetery records — to reconstruct the lives of these women, many of whom married ex-convict husbands and raised families during Moreton Bay’s earliest years of free settlement.

She is discovering far more information on female convicts in early Brisbane and beyond than was thought to be available. I listen to her talk organised by Queensland Archive titled: ‘Offenders, Paupers and ‘Pioneers’: Convict Women and their Families in pre-Separation Queensland’.

In the NSW census of 1851 of the northern district (what was than settled Queensland) there were 5,800 people of 21yrs and older. Of them 2,224 were convicts or ex convict. Of these convicts 107 were women, of which only 2 were sill convicts at that time. Of these, Jan so far, has identified 50 convict or ex-convict women with links to Moreton Bay.

Several convicted female prisoners brought their husband and children with them and several of them settled in Brisbane after they received the Ticket of Leave. Others received their Ticket of Leave elsewhere in NSW or in Tasmania and some of them ended up in Queensland. Not unsurprisingly some the the female convicts also later on ended up in the jail (according to research from Jan Richardson 22 for 71 admissions) that was established after the convict settlements ended (initially in the Old Female Factory). Often for reasons mentioned above: unwanted pregnancies, abandonment, petty thieves, drunkenness. Others ended up as poor and destitute at the Dulwich Benevolent Asylum on Stradbroke Island. Jane has found 19 female ex convicts among those in Dulwich between the mid 1900s and the early 1900s, 15 of them buried in unmarked graves. But there are also a few success stories where ex convicts did make it and became well off citizens.

Details of two female convicts: Hannah Rigby and Marie Langley are provided at the end of the Convict Chapter.