Queensland declared an independent state.

Already in the 1840s, the local people started petition the Governments in Sydney and London, for an independent state. Revered Dr John Dunmore Lang was one of the more senior people advocating for it. Lang’s call for the creation of a northern colony (Cooklsand) in 1844 was defeated in the NSW Legislative Council by 26 votes to seven. The squatters were also active in their lobbying. While the Brisbanites wanted to see a more progressive legal system, the squatters wanted a laisez-fair approach and kept lobbying for more transportation. However, in 1850 the British Parliament passed the Australian Colonies Government Act, which enabled the creation of new Australian colonies with a similar form of ‘Responsible Government’ to New South Wales (a government must have the confidence of a majority of members of the Legislative Assembly). Moreton Bay was specifically mentioned as a districts which was likely to become a separate colony in the foreseeable future. Over the following years Lang heavily campaigned for separation and had of course the full support of the people now living in the various places where people had started to settle. However, these same people were heavily divided of where the capital should be situated in Brisbane, Cleveland, Gayndah, Gladstone, Ipswich or Rockhampton. In the end it came down to Brisbane and Ipswich but in 1859, Brisbane was put forward as the capital.

Of course the border would become the next issues as there were different opinion between the north and the south. The Queen gave her approval and signed the Letters Patent on 6 June 1859. On the same day an Order-in-Council gave Queensland its own Constitution. Queensland became a self-governing colony with its own Governor, a nominated Legislative Council and an elected Legislative Assembly. The border was fixed at 28 degrees south. On her insistence the name of the new state was not to be Cooksland, she gave it the name Queensland.

The Municipality of Brisbane was gazetted on 25 May 1859 and proclaimed by the Governor of New South Wales and the official papers arrived in Brisbane on 7 September 1859.

Because of the delay in communication between England and Queensland the official papers for separation took longer to arrived in Brisbane so the Queensland Proclamation took place after the Brisbane Town was officially established.

On 10 December 1859, Governor Bowen arrived in Brisbane to a civic reception in the Botanic Gardens. On the same day, he was sworn in on the by Justice Alfred Lutwyche and officially marked the historic occasion of Separation by reading a proclamation from the verandah of the house of Dr Hobbs, known as Adelaide House (now The Deanery of St John’s Cathedral). The house was leased by the new government for three years at the cost of £350 a year.

He did set up a three member Executive Council (Robert Herbert as Colonial Secretary, Robert MacKenzie as Treasurer and Ratcliff Pring as Attorney General). In 1866 Herbert became the leader of the Queensland Government. The NSW Governor appointed eleven members of the Legislative Council for 5 years and Governor Bowen appointed 4 members for life. The squatters dominated both chambers, this led to political tensions which are still reverberating throughout Queensland politics.

The Governor’s powers were substantial, he retained the command of the defense, could assent or veto legislation, summon Parliament, dissolve the elective chamber select ministers, formulate legislation and administer law.

At the start of the new State there was no money in the kitty. It was receiving most of its money from land sales, but government expenditure was twice as high. In 1861 the Queensland Government had begun large-scale public borrowing, which was needed to finance not only public buildings such as Parliament House but also railways, roads, bridges, telegraphs and immigration. For example in 1864, a loan of £30,000 was raised for the new parliamentary building and an Act was passed providing for this to be supplemented by the sale of Crown lands within Brisbane. The financial crisis of 1866 further exacerbated the situation.

While the Treasury was empty, Queensland most valuable asset was land. August Gregory was appointed at the Sate’s first Surveyor General and his task was to oversee the land surveying activities that formed the basis of the land sale activities. While there was no corruption involved he did favour the demands of the squatters rather than those of the small landholders. This would remain an area of conflict for several decades.

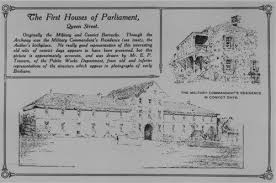

There was no Parliament Building and it were the old convict barracks in Queen Street that were used for that purpose. The building was already used by pro-Governor Wickham and several government offices resided in this building, including the Supreme Court. Significant renovations were undertaken in 1860 fitting for the use by the Parliament.

There was also an ongoing conflict regarding the Governments Garden a left over from the convict era was. In 1859 they had been set aside for the Botanical Gardens. In following years there were numerous conflicts over this site as Brisbane Municipality Council (BMC) wanted to use it for development, however the State didn’t budge so we can now still enjoy it.

Initially the colony was governed by an interim Executive Council until a parliament could be established on the Westminster system of government. After electoral rolls had been prepared, an election was held for twenty-six Members to form the first Legislative Assembly, they sat for the first time on 22 May 1860. In addition, eleven men were appointed to the Upper House, the Legislative Council, for terms of five years (later appointments were for life).

In February 1859 Alfred Lutwyche (1810-1880) had been appointed Resident Judge of what was then the Moreton Bay district of New South Wales. Two years later, in August 1861, he became sole Judge of the new Supreme Court of Queensland and occupied the bench unaided until the arrival of the first Chief Justice, Sir James Cockle, in February 1863.

Shortly after the establishment of the Supreme Court, Lutwyche was op the opinion that the first Parliament had not been validly elected. This brought him in direct conflict with the Parliament and the Executive, who wanted him to resign. However, his concerns were accepted by the British Parliament. Consequently, the Constitution Act of 1867 removed many of the constitutional uncertainties which had existed since the time of Separation in 1859. While he was not popular with the politicians – as he had married his housekeeper, a commoner – he was popular and very well supported by the early settlers in Ipswich, Toowoomba and Brisbane. Although denied the position of Chief Justice following separation in 1859, Lutwyche spent the remainder of his life in Queensland and made valuable contributions to the legal profession. Unfortunately because he was shunned by his peers, his political influence was weak. If that would have not been the case, Queensland would have looked different now as he was far more progressive than his ultra conservative peers.

Squatters dominated Queensland politics for 60 years (and beyond)

Well before the opening up of the penal colony of Moreton Bay for free settlers in the 1840s, squatters started to arrive. Many of them had an aristocratic background and their families were big landholders back in the mother country. They were opportunistic using squattering to take control of large swaths of land. In the process murdering and displacing the Aboriginal people that lived on these lands. Once they had completed their land grabs most of them would return back to England, enjoying the spoils of their wealth.

The squatters were politically also enormously powerful. They felt privileged and wanted the government to to rule in their favour, often using their direct link with the British rulers to get things done their way. When Queensland became an independent state they used the opportunity given to them to dominate the Upper House. Members were nominated for life and they were able to stop any progressive legislation from the Parliament (the Lower House). They were the oligarchs of the time, established their own club (Queensland Club) and were able to frustrate social policies to their advantage. This led to significant stagnation of Queensland being able to develop into a modern state. Throughout the next 60 years there were several attempts to stop their influence and this led to the attempt by the Lower House to abolish the Upper House. This eventually happened in 1922 and more progressive policies could now be introduced. However, the legacy of this period and the policies and especially the political culture that was established is still recognisable in the current political system. While the Upper House was abolished at the same time there was not a new structure that would check the government. While the direct influence of the squatters was gone, there was little oversight that was put in place – what the role a well functioning Upper House has to be. The parliament could basically set policies without the need for any transparency and accountability. An all time low was reached under the government of Bjelke-Petersen. The consequent Fitzgerald Report led to significant reforms and the governance of Queensland has significant improved, however transparency and accountability remain issues until this day (2022)

First Governor George Bowen and the First Lady Contessa Diamantina di Roma

George Bowen had recently served as Britain’s Lord High Commissioner of the United States of the Ionian Islands near Greece. He was the local representative of the British government between 1816 and 1864. At the time, the Islands were a federal republic under the protection of the United Kingdom, as established under the 1815 Treaty of Paris.

While in that post, he married the Contessa Diamantina di Roma on 28 April 1856. Diamantina was the daughter of Conte Giorgio-Candiano Roma and his wife Contessa Orsola, née di Balsamo. The Roma family were local aristocracy; her father being the President of the Ionian Senate, titular head of the Islands, from 1850 to 1856. Most likely she was born on the island of Ithaca, as it hard to understand why otherwise that name became popular in Brisbane.

There were no funds available for to build a proper Government House and it would still take three years before this was build in the Botanical Garden was built. This building remained in use as the official residence till 1910.

Governor Bowen had his enemies in town but among the people he was popular, they requested an extension of his five-year term as governor, resulting in his staying for further two years.

Born on the Ionian island of Ithaca (Ithaki), Greece, Contessa Diamantina Di Roma, became in 1859, at the age of 27, Queensland’s first vice-regal First Lady. In a male dominated society she was widely considered to be a ‘breath of fresh air’ which invigorated the colonial cultural scene and imparted a noticeable ethos of kindness and compassion.

She unfortunately suffered from severe headaches and this was a very dilapidated situation. However, she worked hard to alleviate distress and pauperism. She was instrumental in establishing a range of social, educational , healthcare and cultural institutions.

Diamantina worked together with her friend Eliza O’Connell (Eliza Emily le Geyt) the wife of Sir Maurice O’Connell who served several times as the deputy Governor of Queenlsnd. They set up a maternity hospital officially called, the Queensland Lying-In Hospital. It was opened on 2 November 1864 in a house, Fairview, in Leichhardt Street, Spring Hill. Two years later it moved to a new purpose designed building in Ann Street, between Edward and Albert Streets. This was an eight roomed building with beds for twelve patients and ancillary rooms. In August 1867, this building was renamed the Lady Bowen Lying-In Hospital. It was adjacent to the Servants’ Home which was also founded by Lady Bowen and Lady O’Connell. This was a school for servants in order to make newly arrived female immigrants more employable. This building still exists. In 1889 an extended Lady Bowen Lying-In Hospital was built at Wickham Terrace, currently known as Roma House of Mission Australia for homeless people.

The two Ladies also set up an orphanage in George Street. Eliza’s husband Maurice became a member of the Legislative Council of Queensland

The names Roma Street Parkland, Roma Street, Countess Street, Roma Street Station all refer to Contessa Diamantina di Roma. Throughout Queensland there many more references to her, a good indication how well loved she was. Throughout the State there are many more references to her just to name a few the Shire of Diamantina, the town of Roma and the Diamantina River. A clear indication of her popularity, her hard work and charisma.

Another towering female figure in Brisbane in thes years was the Irish nun Zr. Ellen Whittey. According to the Australian Directory of Biography she established twenty-six Mercy schools, mainly along the coastline to Townsville, these schools had 222 Sisters with 7000 pupils. At Nudgee there was a Mercy Training College for teachers. She also commenced a secondary school (All Hallows’) many years before the state entered this field. She duplicated in Brisbane the types of social work she had pioneered in Dublin, and provided a link between all forms of service in regular home visitation. She died in Brisbane on 9 March 1892 and was buried in Nudgee cemetery. Her work has stood the test of a century of change.

Despite their different religions Ellen Whittey and Eliza O’Connell called themselves friends, this sometimes led to fierce criticism from some of parts of the Protestant communities in town.

Cotton saved the Queensland economy

As mentioned above the new Colony of Queensland started off broke. But luck had it that the Americans at that time stared their Civil War. Prior to the outbreak of the American Civil War, the American south produced almost all the world’s cotton. As war threatened, plantation owners returned to England and English cotton mills ground to a halt.

A new source of cotton was required, and Queensland would be widely promoted as a cotton growing colony and the “future cotton field of England”. The colony government invited mill and plantation owners and workers to re-migrate and re-establish their industry in Queensland.

Under 1861’s “Cotton Regulations”, individuals and companies could lease land and receive the freehold title within two years if one-tenth of the land were used for growing cotton.

After an agreement was made between the government and shipping companies in 1863, thousands of “cotton immigrants” travelled to Queensland, and profits of American slavery were reinvested in Queensland’s and as such provided for the desperately needed income to built up the new colony Down Under.

Cotton was one of the key crops grown at the prison farm on St Helena and was one of the reason why this prison became so economic successful.

It was not until the mining booms in the 1880s that Brisbane and indeed Queensland started to develop.

Military presence

Law and order depended to a great extend on the few military stationed after the opening up of the settlement, now part of a voluntary militia. On his arrival, Bowen complained about the lack of any military at his inauguration. He also reminded the authorities in Sydney that the Colony of Queensland contained an area of 668,207 square miles (730,648 sq kilometers) and that France just had opened a naval basis at Noumea. There were at the time hostilities between Britain and France which was a potential thread to an unarmed Queensland. He almost immediately started discussions with the British Government to send 100 military for the defense of this new colony. In the end he received a detachment of Regular troops comprising two officers and fifty men from the 12th Regiment then stationed in Sydney. On 9 February 1860 he announced that he also proposed to raise a Volunteer force of Mounted Rifles and Infantry. The commanding officer, Lieutenant David Thompson Seymour, became Queensland’s first Commissioner of Police in 1864.

It was not until 1861 before a full regiment of 50 Redcoats was again stationed in Brisbane. The regiment arrived together with three wives and nine children. The soldiers were needed to train the volunteers. From the start there was resentment from the Queensland population against this British Imperial Force, it reminded too much of the convict penal settlement. The military were also accused of being a nuisance in town and were often seen drunk. However, they did receive praise for their assistance during the Great Fire of Brisbane in 1864 (see below).

Veteran officers who commanded detachments in Brisbane included:

- Lieutenant (later Captain) William Crosbie Siddons Mair, of the 12th Regiment, commanded in Brisbane 1865-66.

- Captain Charles Augustine Fitzgerald Creagh, of the 50th (Queen’s Own) Regiment, commanded in Brisbane 1866-68. Creagh and his wife Mary Ann and one child arrived in Brisbane in October 1866. Creagh had served in the Crimean War 1855-56, then later went to New Zealand and served in the Waikato and West Coast campaigns during 1863-66. Soon after arrival in Brisbane with the first 50th detachment, he was appointed Aide-de-Camp to Governor Bowen and served in this capacity from January 1867 to July 1868. He obtained a commission with the 80th Regiment in 1871, before retiring with the brevet (or honorary) rank of major-general in 1887.

- Captain Thomas Millard Benton Eden, 50th Regiment, commanded in Brisbane 1868-69. He arrived in Brisbane in February 1868 in command of the second 50th detachment – the last Imperial garrison force to serve in Queensland.

The 50th comprised two separate companies that served in Brisbane they also provided a military guard for the St Helena Penal Establishment during 1867-69. Although detachments of the 50th Regiment were the last Imperial force to be stationed in Moreton Bay, individual Imperial Army and Royal Navy officers served in Queensland on secondment or in appointments over the coming decades.

Under Governor Bowen military barracks were established at Green Hills (now called Petrie Tce). A strategic site, overlooking the city triangle as it had been laid out by the Penal Settlement Commandants Miller and Logan. The military became neighbours of Green Hill Goal that had been established a few years earlier.

Bowen also asked for guns for the protection of Brisbane and 12 so called Clifton 24-pounders arrived with the soldiers. Most of these guns are still in existence. I will just mention two: one in the City Botanic Garden and one on St Helena. These guns came from the HMS Victory, the ship Nelson died on during the Battle of Trafalgar. These were naval guns and were rather useless for land base use in Brisbane. Nevertheless the Volunteer Artillery Company was drilled to use them. In the end the guns have only been used for salutes and other celebratory purposes.

In 1866 one of the was sent to the Observatory on Wickham Terrace where it was used for firing the time signal at 1.00 p.m. daily. The following year another was sent to the new Penal establishment on St. Helena Island where it was used to supplement the visual signalling system. It served that purpose until the prison was linked to the mainland by telegraph.

Pay was extremely low, they had ‘free’ accommodation and food and not more than pocket money on top of that. Many had little businesses on the side, some questionably legal. No wonder that many soldiers deserted in the early years and others were send to New Zealand to fight in the Maori Wars. Several newspaper reports from this period talk about an unruly lot, lack of discipline and lots of drunkenness. There was an ongoing need to get new recruits to Brisbane to replace the ones lost.

The 12th Regiment was urgently called to New Zealand to fight in the Maori Wars and was replaced in 1866 by 50th Regiment who had completed their tour of duty in New Zealand. They consisted of 92 rank and file under the command of Captain Creagh. Their first task was to repainted the barracks. Interestingly several of the military of the 12th Regiment later returned to Brisbane where thy settled, married and had children. A military hospital was constructed at the barracks for the wounded soldiers coming back from New Zealand. They were also used (without lots of enthusiam) as guards at the St Helena Prison Island. Part of the population remained hostile against the 5oth Regiment and called them a ‘costly toy’.This attitude still also reflecting a lack of community feeling, it was still a time of every men for her or himself.

In 1869 Governor Blackall succeeded Bowen. By that time the Volunteer Force of Artillery and Riflemen counted about five hundred men. Under his leadership the Queensland Government unanimously voted that the imperial military force was no longer needed. Shortly after that the 50th Regiment left Brisbane., ending the presence of Imperial troops in Brisbane. They did leave behind hundred and twenty Old English Rifles, and a little ammunition, three Field Guns without any ammunition and twelve very old and worn Battery Guns, also without ammunition, the Volunteer Force Blackall said was unarmed.

Nevertheless the 50th left an impressive legacy, as under Captain Creagh the volunteers were properly trained. They were also instrumental in a range of other developments, they established a cricket pitch and challenged the local fire brigade, they set up a football team and played against local team and also established a hunting club.

By 1870 all British troops had left Brisbane and the barracks were handed over by to Imperial War Office to the Queensland Government. The defense of the colony was now in the hand of largely untrained and unarmed volunteers. The Queensland Government informed Governor Blackall that there was no need for a military presence in Queensland. In 1876 Parliament approved the purchase of 1,000 rifles for the Volunteer Force.

The Military Barracks were overseen by a caretaker a year later the military hospital was converted into a Lunatic Reception House. In 1875 the barracks became the of Queensland Police, who had also taken over the roll of the state’s defense force along with their policing duties. They added the stables to the complex. The 1870s and 1880s saw a range of geopolitical activities in the Pacific. We already mentioned the French naval base in Noumea, the Germans started to occupy the northern part of Papua New Guinea, the Americans settled in Hawaii and there was a Russian threat as the British became hastily involved in the Crimean War.

In order provide the safety of shipping through the Torres Street Queensland – on behalf of the British Empire – annexed the south-eastern part of New Guinea.

Under this pressure the Queensland Defence Force(QDF) was established and in 1885 and the military moved back into barracks, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel French. The buildings were now renamed Victoria Barracks, after the reigning monarch. At that time they also added the previous Green Hill Goal precinct to its site. The prison was demolished and the prisoners were send to Boggo and St Helena.

Fortifications were now being built at Thursday Island, Kings George Sound and Lytton at the mouth of the Brisbane River. In 1891 1400 troops were deployed from here against the Queensland population, to help break the shearers’ strike.

Bt 1898 the QDF had grown 157 officers and 2300 men and another 800 volunteers. They had a budget of £60,000. After Federation all colonial forces, including the QDF merged into the Australian Defence Force.

The Australian Defence Force (ADF) still occupies the Victoria Barracks in the 2020s.

Municipality of Brisbane

At his arrival of the Bowen’s the Governor mentioned that the town had 7,000 inhabitants, 14 churches, 13 hotels and 12 local policemen. The leading people here were English and Scottish merchants and manufacturers. At the same time all of the above mentioned problems were the same, lack of funds, lack of healthcare, poor housing, terrible infrastructure and so on.

As a young settlement there was not yet a strong community feeling. Most people were simply fighting for their survival. The level of local cooperation and collaboration at that early stage was not well developed. Religion further undermined this. The 14 churches were highly divided and there was great suspicion between them. Each one claiming to be the only true church. This lead to many unchristian acts often led or fuelled by fanatic parsons.

On the other side, once Brisbane became the capital it attracted a new range of often middle class people and even more wealthier immigrants. Basically ignoring the poor state of the town at the time and understanding the opportunities that would arrive. There was an equal massive divide between the two social classes. In 1862, the first two allotments to be subdivided at Petrie Tce centered around Clifton and Sexton Street. The former probably named after the immigrant ship which carried some of the residents here and the latter after the cemetery down the hill.

Testing the political powers in the early days

Bowen inherited what became the political leaders of both the the settlement and state of which many were more interested in their own vested interest than in that of the community. Getting ‘common good’ projects of the ground was an eternal battle. First of all there was the conflict between the town and the state. While the BMC was dominated by local business men, the State Government was heavily influenced by wealthy landowners and squatters living in the country. The interests of both groups were often opposite of each other.

On the BMC side the aldermen were builders, ironmongers, sawmill and quarry owners and many others who would profit from government investments. Decision were often influenced by whom would benefit financially the most, corruption was rife. In the first five years of the BMC there were four different mayors.

The lack of a proper working civil society became apparent in the first few decades of bit the City and the State. When many infrastructure projects needed to be developed, most decisions took far too many years because of many divisions, conflicting interests and not yet well established institutions to manage and oversee these developments.

What also didn’t help was that under the Queensland Police Act of 1863 the magistrates performed a dual task of prosecution and adjudication which was an open door for corruption and the abuse of power. This became ingrained in the Queensland policing system and was finally exposed by the Fitzgerald Inquiry in 1988.

The wealthy country men were influential in building (and financing) Parliament House, Government House, the opulent Queensland Club and various mansions in the area. They received early government investments in a railway for the Darling Downs and after that from here to Brisbane. This at the same time as the city was struggling to get fresh water, build a bridge, buying a fire engine or a even building a hospital. One of the most serious issues in the town was the fresh water supply that had been a health hazard for decades, because of infighting between the councillors, solving this solution took many years. The same infighting led to long delays in building the bridge.

Problems managing the rapid growth

Bowen was also worried by the ongoing attacks of Aboriginal warriors. He just ignored the reasons why the Aboriginals attacked the settlements. Hunting , camping and sacred sites were totally ignored and the increased number of farms here and in the Darling Downs created more and more limitations for the traditional owners of these lands. Farmers were shooting Aboriginals as if they were animals and several massacres took place in these years.

As all of these different issues were not enough, the settlement and the state went went at the same through a very rapid growth period. In the years following Independence up to seven ships per week dropped off new immigrants. They only received three days of free accommodation after their arrival. Many people were living in tents that were scattered around town often for many weeks or even months before they were able to rent a place or built their own slab hut. Many of the early arrivals settled on what was known as Windmill Hill which name was changed in Canvass Hill.

In 1861 there were 318 brick or stone houses, 747 weatherboard and 79 other dwellings. These ‘others’ being basically huts.

Fortunately there was a permanent lack of labourers as well as women. So as soon as immigrant ships arrived they were recruited by farmers and business men. While Brisbane was one of the most remote cities in the more developed world, it did also attract many overseas immigrant nit just from England but also from Ireland, Germany and China. From the very beginning there was hostility against the Chinese people, furthermore they were discriminated against (they could not bring their family with them) and were widely exploited and underpaid. South Pacific Islanders were also brought in as plantation labourers often against their own will. To complete the picture there was also animosity between the Irish Catholics and British Protestants. James Quinn became the first Catholic Bishop in 1859 and arrived with recruited priests and nuns in 1861. With his zeal and energy he was able to build up a strong catholic community. However, his autocratic behaviour made him many enemies even within his own faith. He tried to micro manage everything which made life often very difficult for the above-mentioned Zr, Ellen Whittey. While he had a good relationship with the Anglican Bishop Tufnell, together they tried, unsuccessfully, to divert the tendency towards secularism in education. Tufnell was even reprimanded for it. The other Protestant sections in the community continuously undermined any form of cooperation as they saw that as ‘giving in to the Pope’. He was also severely criticised for bringing in Catholic Irish Immigrants into Brisbane and he had to stop his immigration efforts. He died in 1881 and was succeeded by Robert Dunne.

Natural and man-made disasters.

The rapid growth of the settlement also lead to people moving beyond the original ridges where the settlement was established back in 1825. While flooding occurred regularly because of the many waterholes and creeks in the area it did not have a devastating effect in the convict era as all of the buildings were positioned on the ridges in the settlement. The situation 40 years later was totally different. Most of the low laying areas in the settlement were developed and in private hands. Without any form of flood management built up areas flooded in 1863 and 1864 and had a devastating effect on the town. The flood in 1864 was preceded by a cyclone which caused large scale destruction. Flooding occurred basically every year after this till 1872 and many more times after that year. The lack of proper town planning and flood management management and indecisiveness as mentioned above resulted in lack of proper relief action and little action to prevent further disasters. Further major floods in 1893, 1974 and 2011 caused increasingly more devastation because of over development on the flood plains and the ongoing lack of proper flood management. Ever since that time the issue of the unsustainable development of the floodplains have been ignored.

Around the same time there was an outbreak of Typhoid, most likely linked to unreported dearth on the immigrant ship the Flying Cloud, the surgeon of the ship was later charged. Other avoidable disasters were two great fire of Brisbane in 1864. A month after Brisbane was flooded again, in April that year, 14 houses burned down on the northern side of Queen Street, halfway between Edward and Albert Street. It had started in a shop called ‘Little Wonders” that sold books and miscellaneous articles.

While the fire immediate drew large crowds there was no coordination or any leadership in how to handle this crisis. There were only three volunteer firefighters and they arrived an hour into the disaster but there was nowhere a water supply for the pump, nor had they any authority regarding what to do. Property owners claimed their property rights at this stage there was no legislation that could over rule this. Individualism ruled they were only interested to look after their own premises and had little regard for the others, so in the end they all suffered. With the lack of water and fire fighting equipment, the only thing those involved in the fire fighting could do was the same as they did in the April fire, demolish the timber buildings.

As mentioned above money for a proper fire service had been under discussion for many years. Within two days after the fire a committee was formed with the task to set up a proper fire service. However, the indecisiveness continued with BMC not acknowledging a volunteer fighters service and trying to start one on their own based on council clerks, obviously that didn’t work either, so the bickering continued. Furthermore, the bureaucratic process saw a slow moving process of muddling on over fire fighting equipment equipment. The situation slowly improved and at least they started to prevent people from rebuilding in timber or other flammable materials.

Several of the businesses that were burned down used the empty section on Goal Hill on the east face of Queen Street, between Creek and Edward Streets, near the Old Female Factory (now prison). They build here a range of one level shanties that became known as Refuge Row. Brisbanites complained that they were another fire hazard and it was not until yet another fire in 1877 in a grocery store that finally saw the last one of the timber buildings being demolished. In the 1930s the AMP Building better known as the MacArthur Chambers was built on the site of the Refuge Row.

In the meant time the Female Factory had been demolished and replaced with the current GPO building. In the fire of 1877, the first volunteer fire man was killed. He die from the wounds resulting from an explosion of a cask with burning rum. He is remembered by the James Mooney memorial on the drinking fountain on the corner between Queen and Eagle Streets.

On December 1, 1864 the 2nd large fire of the year burned down a whole block between Queen Street, Albert Street, Elizabeth Street and George Street the town remained unprepared. The fire had started in in the drapers shop Stewart and Hemmant on the corner of Queen and Albert Streets (Hungry Jack). The space behind the shops along those street was filled with small cottages, stables, outhouses, sheds and so, all built of timber, this became a furnace.

Again there was no coordination, no leadership and property owners reluctant to let fire fighters in. In all 25 businesses burned down – including two banks and three hotels – as well as the ‘numerous’ private properties many of them slab huts or otherwise poorly built timber housing. Within a year half of the Queen Street businesses had gone up in fire.

While the Victoria Hotel burned down, the brand new Concert Hall behind it was saved and became a short term ‘hotel’ for the victims of the fire.

One of the buildings that had burned down was that of the Auctioneers Dickson and Duncan. James Robert Dickson became in 1898 the 13th Premier of Queensland. He also became the Minister for Defence in the first federal government in 1901.

Finally early the following year a fire engine was purchased, a proper fire service was set up with proper legislation that allowed them to take control of the situation and overruled individual property rights if needed and finally also building regulations were implemented. The former female prison on Goal Hill became the fire station and a fire bell was installed.

There were no social services so the many families that had lost their homes had nowhere to go, some were reported to use the entry porch of the old Convict Barracks as their shelter. There is no information about their plight which could indicate that indeed little was done for these poor people, they simply had to fend for themselves. It further conforms the frontier situation of the city with at this time still hardly any infrastructure both socially and otherwise.

Reoccurring typhoid and other ongoing healthcare emergencies had also suffered from lack of proper governance. Most cases were brought in by the immigrant ships. Captains were eager to offload their loads and the quarantine rules were not always followed or badly policed. Furthermore there remained an ongoing lack of a proper hospital facilities, healthcare staff and equipment. The opening of the new Bowen Hospital in Herston in 1867 also significantly improved the health care situation in town (now the Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital). The hospital in those days depended on voluntary contributions to remain afloat, and there was an ongoing scarcity of funds (this situation continued until 1917 when it was taken over by the Queensland Government).

Finally infrastructure development got underway

As mentioned, cross-river transport for the first 20 years was by ferry. Finally the decision for a bridge was made. The foundation stone for the first bridge – called Queen Bridge – was laid by Governor George Bowen on 22 August 1864. However, problems continued, lack of funds saw the original design of an iron bridge downgraded to one that would temporarily be based on wooden piers. However, shipworms rapidly noticed the structure and in 1867 a large section of the bridge collapsed.

Following the financial crisis of 1866 there still was no money available another wooden bridge was constructed in 1874. The name was now changed to Victoria Bridge. This bridge was swept away by the flood of 1893. This time it was finally replaced by an iron bridge. In 1896 a one way bridge was opened, a year later the 2nd lane was added. In 1969 this one was replaced by the current concrete built bridge.

By 1864 the population had grown to 12,500 people and the whole of Queensland now had just over 60,000 inhabitants. By the end of the year that number had grown to close to 75,000, an incredible rapid increase of just under 25%.

Despite the management problems, the 1860s and 1870s started to see improvements, the Normal School was opened with separate sections for boys and girls. The governor could move into what is now the Old Government House in the Botanical Gardens. The foundation stone of Brisbane’s first town hall in Queen Street was laid on 28 January 1864 by Queensland Governor George Bowen and completed three years later. In the Old Windmill a museum was established. The William Street Saw Mill claimed to be the first true factory and the first part of the new parliament house got build. Gas street lighting arrived as well as a telegraph service to Ipswich and to Sydney. The first telegraph office was established in 1860, in Dr John Lang’s Evangelic Church, on the corner of William Street and Telegraph Lane (renamed to Stephen’s Lane). Perhaps most importantly clean water was finally provided piped from the newly established Enoggera Dam. Which was constructed in 1866, on the upper reach of Breakfast Creek.

Tom’s daughter Constance mentioned that we should also recognise Tom for his contribution to infrastructure. He literally was a trailblazer. He marked the road from Bald Hill in Brisbane to Humpybong (Red Cliffe). He also marked the road from Bald Hill to the Pine River (where he had his farm).

Royal visit – 1868

At the last-minute Brisbane was included in the first-ever Royal Visit to Australia. This took place in 1867/1868 by Prince Alfred Duke of Edinburgh, the second son of Queen Victoria,. The trip had been a year in the planning and a special combined sailing ship/steamer had been built for the occasion, the HMS Galatea.

As Brisbane was a late addition to trip the preparations had to been done in a hurry and that resulted in a few hiccups. Also because of the above mentioning political manoeuvrings Governor Robert McKenzie was forced to also include the Downs into the project, with led to a train trip that ended in the Prince sleeping a ‘railway shed’ in the non-existing village of Jondaryan alongside the yet unfinished railway track. The Emu hunt planned for the following morning had to be cancelled as the horses didn’t show up. So back in the train and instead the Prince took a tour of Toowoomba.

The Prince spent about a week in Brisbane and on the 25th February 1868 he was greeted by an enthusiastic community. However, it was also interesting to read in the local papers of those days that the enthusiasm was wearing off rather quickly and towards the end of the visit there were fewer people that kept cheering him on.

Tom Petrie had in a hurry organised the participation of Turrbal people from the various tribes around Brisbane who appeared as warriors with full body paint. However, the Aboriginal people were puzzled by the fact that such an important man was dressed in ordinary clothes, they mentioned that the local authorities, with their top hat and tailcoats looked more impressive.

During the stay the Prince laid the foundation stone of the original Brisbane Grammar School at Roma Street, the School was originally to be named Prince Albert School. It should right in the middle of the current rail yard. In was opened the following year. It was a splendid Georgian building but had to be vacated a decade later to make room for the rail-yards and a new school (the current want) was built on the corner of Countess Street and Gregory Terrace.

One of the most remembered events of the almost 6-month stay in Australia, was after his departure from Brisbane during his stay in Sydney where he was the victim of an assassination attempt at Clontarf, by Irishman, James O’Farrell. As mentioned above this was at a time of high tension between the Irish Catholics and the British Protestants.