Holocene

With the warming of the climate we enter the geological era where we still live in. It is seen as an interglacial within the still continuing Ice Age. It this geologic time frame that has been most condusive for the developments humans.

In northwestern Europe we see that Britain was connected to Europe during most of this period and in 2009 human remains were dredged up from this area (Doggersbank) indicating that modern humans had been dwelling here 40,000 ago. During the Middle Stone Age, the land in what is now the Low Countries became slowly more habitable. From 6,000 BCE onward sand dunes started to create a more habitable environment that protected the land from the sea. Enormous amounts of melt water started to fill up what is now the North Sea. Over a period of 3,500 years, water levels increased on average by 2 meters a century. By 7,000BCE sea levels had reached more or less the current coastline and the British Isles were permanently separated from continental Europe.

Forestation started first in southern Europe around 12,500BCE and from than on we see our Palaeolithic forebears moving north. Hunting animals changed too, in a more forested environment the prey is now red deer, wild boar and wild oxen. Huge pine forests started to appear in north western Europe. The climate was still very dry and there is evidence that massive forest fires blazed through large part of the continent around 12.000BCE. [6. Onder heide en akkers, Evert van Ginkel and Liesbeth Theunissen, 2009, p49]

Changes to the environment

Between 10,000 and 6,000BCE, after the ice sheet in northwestern Europe retreated slowly also here forests started to arrive, taking over the tundras.This change in environment had enormous consequences for the early hunter gathers who had been visiting this region during the previous millennia. It is estimated that the number of hunter gathers on the north western plain – between the rivers Oder and Maas – would not have numbered much more than around 1200. In the early part of this environmental change they could still follow the massive herds tracking from south to north, where they grazed on the tundras and at very predictable times the people could make their kills. As there are fewer animals in a more forested environment, human population started to decline. The tribal groups were smaller and lived further apart than in previous millennia. Social structures became simpler and fewer technological and artistic innovations appear during this period.

The climate however remained rather cold; the ice didn’t start disappearing from Scandinavia until 6,000BCE. The many lakes in Finland are still a reminder of that retreating ice. Other leftovers from the Ice Age are the morasses of northern Europe. With sea water levels rising it became increasingly more difficult for rivers and creeks to drain into the sea. There were water stagnated large morasses started to form. A large one of them is the Bourtanger Moor; an impregnable 3,000 square kilometre morass that was formed around 5,000BCE, this wilderness extended in the north from modern-day Friesland to well into Germany. During summertime there were some drier stretches which were used to herd cattle. However, there were no boundaries and this often led to violent conflicts between farmers. It was not until 1867 that even the official international border between Prussia and the Netherlands was drawn.

-

Peat winning (Drenthe) Picture 1972

On the edge of this vast wilderness expanse, around 1600AC, the Budde family in Wietmarschen started to carve out their living by reclaiming peat land for agriculture purposes, there did so as serfs of the local monastery.

Also in the ‘dry’ land peat morasses were formed in the period following the Ice Age. In Brabant there are still remnants of the Peel morass it is a high laying peat area, which formed because of the poor drainage situation that occurred after the Ruhr Valley Graben (RVG) was formed. Both the coastal areas and the rivers became dynamic regions, sometimes there was land sometimes there wasn’t.

As we will see below, when Europe was reforested the early peoples had to start from scratch again, carving out their new livelihoods from these dense forests. However, for those living at the time these changes would hardly had an effect on the developments of each of the generations that were part of what at the time would have been a very slow, hardly noticeable change. Nevertheless, hunting on tundras is rather different than hunting in the forests.

These forests were very thick indeed. Even the Roman chronicles still talk about the impregnable forest (Silva Carbonaria – coal forest) which covered most of the area, we now call Brabant -from the Scheldt to the Arduenna forest (between Trier and the Rhine). In their chronicles it is stated that north of the Arduenna an extensive area of morasses existed (the above mentioned Peel).

For most of the time humans have existed their lives has been totally dominated by nature and its features were the geographic boundaries of their life. Most modern boundaries be it of countries, regions or cities are, in its origin, based on natural circumstances and natural features. It is only in the last 100 years or so that this link with the land is getting lost. However, we are already forced to revisit this situation as we will have to take the environment into account in all we do, we are re-learning that we can’t take nature for granted.

Changes in the society

Throughout Europe and Asia, for most of the Palaeolithic, the way of stone-age life remained largely unchanged. More sophisticated specialised tools started to occur in the Low Countries around 8,800BCE. There are three periods: early, middle and late and the boundaries are 8,800, 7,100 and 6,450.

Archeologists conclude that the Mesolithic people here were indeed the decedents of the Ahrenburg people (see below). Flint stone spearheads from around 7000BCE found in the region around Ootmarsum are remarkable similar to those of those earlier reindeer hunters. However, by that time, the number of tools and smaller working devices had significant increased in comparison to the Paleolithic.

However, remarkable changes that started to occur in the Mesolithic would change forever the way people lived. This was largely driven by the environmental changes mentioned above. But as the environment was different throughout the region we see significant time differences in these developments. While all societies went through a similar process from hunter gathers to farmers and through different cultures, stone age techniques, pottery, copper and bronze, there was often a time difference of several thousands years between developments in the Middle East/Mediterranean, the Eastern Steppes and northwest Europe.

Recent research revealed that rather than hunting predominantly large game, which happened during the Palaeolithic, the emphasis moved more to marine and freshwater food complimented with food from smaller fleeter-footed animals such as red deer, pigs, elk and auroch. Some scientists argue that it was fish food that had a significant influence on the developments of our brains, which helped in developing the cultural and technical innovations which started to occur during the Middle Stone Age.

This change also effected the cave art as we had seen that emerging in the Late Paleolithic, it totally disappeared as it was tied to the now extinct large game populations.

Burial practices also started to change, large burial grounds are appearing, especially from 6,500BCE onwards. This indicates more complex societies; most of these people lived in coastal areas or adjacent to lakes and rivers. It started to make sense to put more time and effort in these places. This led to innovations in technology in these stages still Stone Age technologies, but nevertheless very significant indeed. Surpluses could be created, which could be traded. These more productive places allowed for the gathering of (individual) wealth. There are indications that within these societies there was competition for prestige and power.

Hunter gatherers societies had remained small throughout their history (groups of around 30 people). This continued and remained the case well into modern times and that also provides clues to how previous generations would have behaved under such circumstances. In relation to my own experience with the Pitjantjantara people, the mobility of hunter-gatherers required them to limit the size of the group and in particular the number of children per mother. If a women would have more than one small child to feed it would be difficult for the group to move around. Carrying one child around, while gathering food, was possible, more would be rather difficult. Children were suckled till they were 3 or 4 years of age, this was a natural way to prevent conception. Once around 4 years of age children could move around on their own with the group and could even become involved in food gathering.

Agriculture was in many aspects a turning point in human history, from this time onwards the key driver for change became population growth. With a settled life, women could conceive children more closely together and that was exactly what started to happen. However, this happened first in the Middle East and it took millennia before these developments reached north-western Europe

Early modern human activity

Cro-Magnon people

As we saw in the Paleolithic period, the Cro-Magnon or European Early Modern Humans (EEMH) settled in Europe. In the northern regions they were known at the reindeer and mammoth hunters, they roamed the area – depending of the weather – during the period between 40,000 and 10,000 years ago.

The first evidence of the Cro-Magnon people in the Low Countries (North Limburg) is around 25,000 years ago, just before the climate started to turn colder again; this culture is known as Gravettian (28,000 – 22,000 years ago). These very early arrivals here most likely hunted smaller forest animals and lived in small groups, perhaps as small as a single family.

As the climate deteriorated people began its long migration south; eventually reaching Spain and founding what became a refuge for all humans during the coldest millennia of the last Ice Age.

This led to a slightly more densely concentration of people, especially when sheltering is taken into account. Good caves where of course premium real estate as that provided protection against the cold.

At the same time the forest and its animals retreated and the tundras attracted larger animals. This changing environment required a more communal effort and these circumstances might have been the reasons for people to form larger tribes, allowing them to share caves and to hunt in teams. These changes as well as all of the natural activities in general would have required our earliest forebears to have accurate information of the world around them and to be able to disseminate that (which plant can be eaten, which animals are poisonous, which plants have healing powers, etc).

For the next 15,000 years people rarely traveled further north than the Ardennes and the Rhine Valley.

As the climate warmed, the scattered clans started the march back to the north to reclaim the once frozen lands. They reached the British Isles and left an indelible record in the limestone caves of Cheddar Gorge. In 1998, DNA was recovered from the famous skeleton known as Cheddar Man and analysis showed that it belonged to the clan of Ursula. In a dramatic demonstration of genetic continuity, they found that a teacher at the local school, only a few hundred yards from the cave entrance, was a descendant of the same clan.

The reindeer hunters

After a very cold period between 16,000 and 13,000BCE, known as the Old Dryas, a period of relative warmth arrived: the Allerød, in the following 500 years people started to reappear in our regions. They were following the reindeer herds over the tundras – which covered most of Europe . They were opportunistic hunters and often concentrated on single species mainly reindeer and sometimes wild-horse. There were several cultures of these hunter gatherers that have left their traces back in northwestern Europe, they emerged around the same time and could well have been related to each other. They are known as: Hamburg, Federmesser, Magdalenian and Ahrensburg. There are some suggestions that perhaps already at these early times some form of herding started to occur [7. The Making of Mankind, Richard E.Leaky, 1982, p194].

Traces of the Upper Palaeolithic Hamburg culture have been found north of the rivers, in Friesland and Drenthe (12,000BCE), these people were true reindeer hunters, most probably arriving in our region from the east. They were hunting with the spear and the spear-thrower. These hunters travelled around in tents made of reindeer skins and these didn’t look much different from those used by the Inuits and Eskimos.

Artifacts dating back to this period where found by Sweikhuizen in South Limburg and are linked to the Magdelenian culture (17,000 -7,000 BC).

Both the Hamburg people and the Magdelenian people started to move southwards when the climate started to cool again around 12.100BCE. It is here that the Magdelenian people created the famous cave paintings.These are concentrated in three regions. Two in south-west France in the Dordogne (Lascaux) and one on the slopes of the Pyrenees and one in the Cantabrian mountains of northern Spain (Altamira). Their art includes a range of techniques: drawing, engraving, stencillings, painting, modelling in relief and in the round, and sculpturing in relief and in the round – almost every process we know today. [8. Man before history, Creighton Gabel, 1964, p37]

The Feddermesser people used tools that indicate that they were hunting aurochs and wild horses, indicating a warmer climate. In Brabant alone over 130 archeological sites have been linked to these people [9. Onder heide en akkers, Evert van Ginkel and Liesbeth Theunissen, 2009, p49] Some of these campsites indicate a possible annual return to these sites, most likely in relation to the migration patterns of the animals they were hunting. Their campsites were nearly always situated on the southern side of the sand hills or on the northern and western shores of forest lakes (fens).

A thousand year later their ancestors, people known as the Ahrensburg culture (See video clip: National Museum Leiden), also reindeer hunters, also started to hunt with bow and arrow. Archaeological evidence of these people indicate that they also hunted below the rivers, including in Brabant (Geldrop) dating back to around the same time. They concentrated on the higher sand grounds, rather than the river flats that separated this part of the Low Countries from the northern parts. They followed the reindeer migrations and these animals provided all they needed: food, leather, antlers and bones (tools).

During the Paleolithic and Mesolithic there is very little difference between human activities in the northern and southern halves of the Low Counties. This indicates that the whole area was one, rather flat, toendra/forest, only much later are the rivers going to play a dividing role in this with different sub-cultures developing on either side of this divide. By then we see that raw material used for their tools and weapons often had different places of origin.

The Ahrensburg people (11.000 – 10,500) were the last of the reindeer hunters, their tools indicate that they were highly specialised in this type of hunting. Other archeological evidence suggest that they often hunted in very large groups, indicating very large herds. From this time onwards cold weather and food scarcity did no longer force people to move out of north western Europe from now on people started to settle permanently in this region. It is tempting to see these people as the ancestors of the north western European people.

There is one (disputed) artifact from the Ahrensburg people in the Low Countries, known as the Venus of Mierlo in Brabant; an engraving of a dancing girl.

The last hunter gatherers in northwest Europe

There are several archaeological finds from the hunter-gatherers camps dating back as far as 8,000BCE, remnants of a pine wood canoe were uncovered in Pesse, Friesland, also dating back to the Mesolithic. (See video clip: National Museum Leiden) Similar finds were made in the Bourtanger Moor; dating back to 5000BCE and in the area around Ootmarsum. There are also plenty of archeological finds of flint stone artifacts on the higher grounds in the southern parts of the Low Countries. Some of these camp sites have been visited many times, some perhaps for more than a century. Aboriginal middens in Australia sometimes represent a history of over many millenia.

Fishing hooks from the middle Mesolithic were dredged up from the river Maas near the village of Lith not far from Oss. The first wooden statue found in the Low Countries dates from probably 5,300BCE and is known as the Little Man of Willemstad (a town in west Brabant). (See video clip: National Museum Leiden)

However, how and where these people lived during the Mesolithic is still largely unknown, the many archaeological finds don’t tell us anything about the life of them. Slowly we start to see differences between groups living north and south of the great rivers. Different relations and trading networks started to create differences between these two groups of hunter gatherers.

By 5,000BCE the hunter gathers had largely disappeared from the landscape and in some parts of the Low Countries (Drenthe, Limburg and South Holland) the first glimpses of the Neolithic people started to emerge, strangely so far no evidence from early agriculture have been found in Brabant, perhaps indicating a discontinuation of human occupation in this region during this intermediate period.

The warmest period sofar since the end of the last ice age occurred around 7,000BCE, when temperatures were 1-2 degrees higher than present. This period is known as the ‘Atlantic’ (8.000-5,000BCE). While this occurrence is evident in archeological excavations it again doesn’t tell us what effect this had – if any – on the local population and their developments.

Proto-agriculture developments

The hunter gathers in the Paleolithic period maintained very similar cultures while widely dispersed around the globe. We see a similar biological driven development happening at the end of the last Ice Age. A combination of developments saw people, independently from each other, slowly started to move into agriculture; climate change, growth in population and social structures (eg religion?) all might have played a role in this process. This happened in Papua New Guinea, China, India, Mesopotamia and Central America. From these core areas the agrarian culture started to spread further around the globe partly based on the diminishing effect of the Ice Age and partly based on the need for more agriculture lands which resulted in increasingly lesser productive lands being incorporated in this development. This development clearly shows the unity of human society, at least on a high level of social development, there was no difference between east and west, north and south, more or less knowledge or sophistication.

In this overview however, we will concentrate on the developments as they started to occur in the Middle East (Mesopotamia/Anatolia) as from this agricultural core social and economic developments started to spread through Europe.

Developments started to happen in the eastern Mediterranean (Levant) during the Alerod period at the end of the last Ice Age around 13.00 years ago, it was a warmer period that resulted in a rather lavish natural environment in this region, known as the Fertile Crescent.

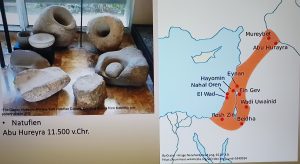

The warming climate resulted in wild wheat and wild barley encroaching upon the sparse steppe. This would allowed the hunter gathers to include a larger amount of cereals in their food pattern and this perhaps created the idea of a different life? The Kebaran people in the Jordan Valley are known to have gathered wild cereals during this period. As early as 12,500BCE small settlements of around 200 people started to evolve here. There are non-conclusive indications that cultural influences might also have arrived from northern Africa (Sudan). The first houses were most probably based on earlier semi-permanant structures and are round or curvilinear, with domed roofs. This is known as the Natufian culture; they evolved from the Upper Paleolithic Kebaran hunter gathers who had been living here since 18,000BCE.

This early proto-agriculture stopped when a rapid deterioration of the climate resulted in a return of Ice Age conditions a period known as the Younger Dryas. The people were forced to adopt, some settled in small pockets where water and fertile soil remained available (Jordan Valley) , others returned to a hunter gathers existence. It has been argued that these difficult living circumstances might have led to the people on fertile soil to start cultivating the wild wheat.

This early proto-agriculture stopped when a rapid deterioration of the climate resulted in a return of Ice Age conditions a period known as the Younger Dryas. The people were forced to adopt, some settled in small pockets where water and fertile soil remained available (Jordan Valley) , others returned to a hunter gathers existence. It has been argued that these difficult living circumstances might have led to the people on fertile soil to start cultivating the wild wheat.

With a return to the warmer weather around 11,000 years ago we see two interesting developments among the Natufians; agriculture now started to evolve around farming communities, while the hunter gathers in the hills started hearding goats. The Natufians are also credited for the domestication of the dog.

In Tell Abu Hureyra on the Euphrates in northern Syria archaeological evidence shows the transition from hunter gatherers to agriculture and at the moment this site is earmarked as the first agriculture village in the world – dating back from 11,000 years ago. They were also among the first to built stronger rectangular buildings – a revolution in architecture -plaster was also widely used indicating that their activities went beyond simply functionality, and lime was also rather expensive to produce. To plaster a house the production of lime, as the basic material for it, required approx six tree in fuel. For the first time they were building homes rather than houses (some of this house architecture still persist in the Middle East).

We also find this plaster back in masks that are used on some of the statues found. It has been suggested that these were death masks and could be linked to mythical ancestor worship.

Some of these pre-agriculture communities evolved as a natural consequence of permanent settlement into early trading/market posts examples here are possibly Ain Ghazal (modern Amman), Jericho in Canaan and Catalhöuyük in Turkey.

Steven Mithen (see above) has another interesting theory about how early agriculture might have started. He suggests that domestication was a result of of frequent ritual and construction activities in relation to this, which for example took place at Göbeki Tepe (southeastern Turkey). In order to facilitate these large activities, originally the wild wheat that grew here plentiful, was harvested. Over time some grain might have been spilled and consequently germinated.

The sacrifice of animals – as seen in many burial sites – might have resulted in corralling these animals in order to have a ready supply of them for that purpose. Overtime the religious power of these (wild) animals might have weakened and that rational uses of these increasingly more domesticated wild animals took over.

It is interesting to consider that it was possibly religious experiences that led to these revolutions. The massive stone works at Göbeki Tepe certainly indicates a link between the two developments. Similar construction are being discovered elsewhere in the region which might shed more light on the people and their culture and religion. They certainly marvel the much later stone cultures in western Europe such as Stonehenge.

Archeological evidence in Jericho shows that the transition from hunter gatherers to urban settlement took place within 1,000 years. Archeaobotonist estimates that this would have been the period over which the mutation from the low yield crop to a domesticated higher yielding crop would have been evolved. In this way a rather gradual and natural transition from hunter gathering towards agricultural could have happened.

Societal changes

Now, new and rather large settlements started to include storage places and weirs and from this time onward we also start to see defence structures around these settlements. These more permanent settlements were also the ideal place for the development of agriculture, which as we saw started to arrive at the end of the Mesolithic.

Such societies could of course feed far more people than the previous hunter-gatherers and this became the start of the population explosion which is still continuing during modern times.

At the same time there were also disadvantages of this change, more time was spend on work, there was less meat in the diet and less security of food supply in the case of crop failures (at least once every 4 years). Also the social structure changed dramatically from a sharing community that at the end of the day ate most of the food that they had gathered to one were food was grown and accumulated over time. Sharing became a problem as I experienced during my stay with Aboriginal hunter gathers. When people moved out of this culture into the ‘modern world’ where they perhaps had a farm or a shop, family members would visit them and their culture would demand sharing, obviously a unsustainable situation for a farmer or a shop owner.

The various pastoral and agriculture communities that started to evolve however, varied greatly. Some areas hunting remained a key part of their lives for several millennia in particular in the more temperate regions all the way from China to western Europe. In Central Europe domestic animals dominated their societies. While on the loess grounds domestic animals played a minor role. Neolithic Chinese only kept pigs.

While talking about the Neolithic Revolution it is important to realise that under different conditions of climate and soils different civilisations developed. This was further influenced by elements such as self sufficiency and subsistence, this created a patchwork of isolated economic structures and this in turn stimulated the developments of different cultures. This is very visual in the the various beaker cultures.

All these variations in developments and cultures also makes it difficult to put a start and an end the the Neolithic period. Perhaps the starting date of around 6000BCE is a good point, however, in some parts of the world this period lasted to even into the 20th century. There are also indications that a rather sudden cooling period known as the 8.2 kiloyear event (or 6,200BCE) had something to do with this. This event lasted for 300 years and created drought in North Africa and the Middle East. This will have resulted in changes in habitat, which will have caused migration and change to food production patterns, which might have been the cause for the development of the irrigation systems in Mesopotamia, which in turn lead to the production of surplus crops and thus wealth and this was the driving force behind the emerging city states.

While Modern Men easily adapted to the hunter gathering lifestyle they were also easily adaptable to the agricultural lifestyle, from sharing to saving however, also meant a different way of dividing labour. Women now stayed at home and in general looked after the fields, men worked with the herds and therefor traveled more and met more people. Local political structures now only started to involve men. While agriculture produce was mainly used for consumption, livestock could be sold and started to generate cash, which provided an economic advantage for the men.

A community based on ‘saving’ automatically leads to defense, you can run away from an animal you are hunting but not from a field you are tending. Thus humanity started adopt to this new lifestyle that increasingly started to involve war. Totally new social and political structures were designed around this new society with control functions hierarchies and organised religion. It a matter of adaptation, something humanity will again have to do in the face of the new challenges of this time and age.

With more permanent villages and cities it also became necessary to keep the animals closer to where these people lived and this led the change from herding to the domestication of animals. This in turn led to a new economic development that of agriculture/city societies, whereby farmers also started to produce for people in cities.

-

Sheepfold Exloo Drenthe

Sheep were the first to get domesticated (10,000BCE), followed by goats (8,000BCE), pigs (7,000BCE), cattle (6,000BCE) , horses (4,000BCE) and camels (1,000BCE). Out of the thousands of wild animals only 14 have been domesticated.

These developments rank among the most important discoveries of mankind. Men were now free from their total dependence on wild food resources and they therefore became less affected by the availability of these resources. Having control over food production also resulted in surpluses and this in-turn had an enormous effect on economic, social and political developments.

Children also played an important role in this as they could be involved from a relative young age towards in sheep herding, weeding, scaring of birds, etc. They were also critical in looking after their parents when they could no longer work on the farm. An important role they still perform of some of the remaining traditional pastoral and agricultural communities.

Land degradation and deforestation led to a decline of the cultures in the Middle East. This is evident in the houses they were building around 7000/8000 BCE, which increasingly contains less and less wood. After an occupation that stretched over 2,500 years the city of Ain Ghazal was abandoned.

People now started to cross the Mediterranean and further north from Turkey they moved into the Balkans. Most likely they followed traders who had already at earlier occasions ventured into these regions. The farmers who followed started to clear patches of forest and colonised these new densely forested lands – occupied by hunter gathers – they were seen as dangerous places were you easily could get lost. Isolated farming communities started to emerge along the rivers. This started a process of migration of people and ideas further into western Europe.

The new immigrants faced many obstacles, technologies that were developed in the Middle East did not work in these new lands. the climate was colder which had its effect on the needs for warmer houses, and clothing. Plants that grew ‘at home’ did not flourish in these different climates, they had to learn to work with the seasons. With an abundance of wood, houses were now made out of timber and the famous European long house started to make its entrance.

By 5,000 BCE agriculture had reached Greece and had spread into Balkans along the river the Danube. By 4,000BCE it had reached the Rhineland. It also spread along the Mediterranean and reached Spain and France around the same time.

New challenges were faced here with dense forest and colder climate this led to seasonal farming and mixed farming, the building of long houses and warmer clothing made from wool.

By 3,500BCE a new threshold was reached in human history with a well established peasantry dominating the human life style in the Near East and rapidly spreading into Europe, India and China.

Arrival of the Indo Europeans

While the early human migration pattern had a south north movement (out of Africa), the migration pattern now started to move east-west. This would continue for several millennia. The steppes formed a highway between east and west for the Huns, Avars, Lomabards, Bulgars, Turks and Mongols, it brought agriculture and pastoralism, urban revolution, religious concepts and so on.

The first arrivals, the Indo Europeans can be traced back to the Eurasian Pontic-Caspian Steppe Cultures. Early hunter-fishing communities started to settle along the rivers in this area after the ice started to retreat. The steppes were the ideal environment for prot0-pastoral practices. Which arrived here via the Natufian developments as mentioned above.

Pastoral communities are more mobile than agriculture based communities. They need to maintain contacts over larger areas to sustain their breeding networks. And such communities are a pre-requisite for the migration patterns that started to develop and which continued with the Huns and Mongols until the Middle Ages. Many different people from many different tribes settled the area and the result of that mosaic pattern is still very much visible in Europe. It has delivered its vitality but also results in devastating wars the most recent being those in the Balkan, Caucuses, but also WWI and II can also be traced back to tribal conflicts. But also smaller conflicts such as the Basques in Spain and the language problems in Belgium can be linked back to the tension and the dynamics involved in the migration of different tribes.

There are several theories on why this migration happened:

- A drying of the climate caused people in the Near East to leave this area.

- Agriculture resulted in population explosions and that this caused the spread.

- The rising waters after the Ice Age caused the Mediterranean to burst into what is now the Black Sea, this caused a displacement of people in the area, which resulted in the migration (Great Flood stories such as the Gilgamesh and Noah’s Ark could be related to this natural disaster).

Mobile pastoralists outpaced the agriculturists in capital accumulation (animals) and thus were able to dominate over other communities they encountered during their nomadic travels. Add to that the use of the horse and the wagon and we are encountering a formidable new force born on the Russian Steppes. In general these people proved to be more innovative and as such were at a social advantage in comparison to agriculturist communities. But it were both the farmers and the pastoralists who eventually spread from Mesopotamia to the Mediterranean and beyond.

By 6,000BCE steppe nomads had developed themselves into a thriving early warrior-pastoral culture. The eastern branch migrated east of the Black Sea and became the forefathers of the Indian and Iranian people. They also were the people that eventually created the eastern empires such as the Persian one.

Moving further west, another branch of the Indo Europeans started to cross the Urals. From here they spread into Balkans some 1,500 to 2,000 years later. They significantly disrupted the agriculture culture settlements that had developed here.

There is strong evidence that together with new farming and pastoral technologies and expertise, also pottery was spread throughout Europe by the these people.

In the east, where the agriculture societies were disrupted by the Indo Europeans, we also start to see the development of more and more fortified settlements, indicating wealth creation and wealth protection.

Very few fortifications developed around that time in other parts of Europe. One of the few early agriculture communities that might have had some fortification is in Hesbaye (southern Belgium). There is evidence that this was enclosed by a ditch of defence possibly against the hostile native hunter-foragers to their north.

The first cattle herding people reached England between 3,000 and 2.500BCE around the same time the Swiss lakes and Southern Scandinavia was settled by farmers and herders.

The specific physical characteristics of the Indo-Europeans still persists in the north west Europeans of today.

Continuation: The Neolithic

The History of Northwestern Europe (TOC)