The Moluccas: Islands of Spice, Memory and Continuity.

A key element of our trip was to travel beyond Java and visit the legendary Spice Islands—long present in Dutch memory and increasingly acknowledged for the brutality of the VOC era and the later colonial period. Dutch power here runs from the early 1600s, when the Portuguese were expelled from Ambon (1605) and Fort Oranje was founded on Ternate (1607), through the VOC’s dissolution in 1799 and into the Dutch colonial state, up to the Japanese invasion in 1942 and the Indonesian Revolution after 1945. We wanted to place this history in context by experiencing the islands themselves: to see the land where cloves and nutmeg still grow, walk the forts where control was imposed, and meet people for whom these layers remain close to daily life. On this journey we visited Ternate, Tidore, Ambon, Saparua and Nusalaut.

Geography, People, Economy.

The Moluccas divide into two clusters. The North Moluccas centre on the volcanic islands of Ternate and Tidore near Halmahera; the Central or South Moluccas include Ambon, Saparua and Nusalaut, with the large forested island of Seram to the north. The islands stretch between Sulawesi and Papua (former Netherlands New Guinea), directly north of northern Australia, marking one of the oldest cultural and trading crossroads in the Indo-Pacific.

Ambon to Ternate is about 500–600 kilometres, a flight of around ninety minutes. Across the islands we visited the population is about 1.8 million, with Ambon the main urban centre. All the islands are heavily forested, much of it inaccessible jungle, with relatively few mountain villages; most people live along the coasts. Each village clearly marks evacuation routes and assembly points for eruptions, earthquakes and tsunamis. The economy is village-based: smallholder agriculture, fishing, local markets and government employment, with remittances from Moluccans in the Netherlands.

Indonesia is clearly a young nation, with schools in every village, we were impressed by the large universities now operating in places like Ternate and Ambon. This growth in education will shape the country’s future. The students and young people we met were politically conscious and outspoken; it is from their generation that the drive for change will come.

Religion, Adat and Indigenous Communities.

Religious patterns reflect history. Saparua and Nusalaut are predominantly Christian; Ambon is broadly half Christian and half Muslim; the North Moluccas, including Ternate and Tidore, are mostly Muslim. Ben

eath both faiths persists adat—customary law and an older spiritual relationship with land and ancestors; especially on the smaller islands we saw many homes with family graves carefully maintained in the front garden. On Seram, Alune and Wemale communities maintain strong adat traditions, including sasi, which periodically closes reefs, forests or groves to allow resources to recover. In that sense, pre-Islamic and pre-Christian animist frameworks are still present and influential, especially in the interior. In music and dance we also sensed links across the South Pacific (Melanesia); in some places even people’s appearance, such as frizzy hair – such as our guide Stevy – quietly hints at older oceanic connections.

Before the Europeans

Before foreign ships arrived, cloves grew naturally on Ternate, Tidore and Makian and moved along inter-island trade routes. The sultans of Ternate and Tidore ruled through kinship networks, ritual authority and the ability to regulate maritime commerce. Coastal settlements were open to exchange; the mountainous interiors, especially on Seram, held to their own autonomous order under adat. The sea connected rather than divided: goods, marriages and ideas travelled easily along these routes.

The Portuguese, the Spanish and the VOC.

The balance changed when the Dutch VOC arrived in the early seventeenth century. The VOC did not seek mere access; it sought to control production at the source. By aligning with Ternate, it expelled the Portuguese and eventually forced the Spanish to withdraw to the Philippines. From there VOC power spread, but it was never uncontested. Resistance recurred throughout the VOC period: Ambonese communities rebelled against forced deliveries in the 1620s; Seram highland groups resisted village relocation and clove-tree destruction enforced by hongi expeditions in the mid-seventeenth century; Tidore periodically tried to reassert autonomy with support from Makassar sailors.

Forts and what they were for.

The VOC secured its control through a chain of forts. We visited Fort Duurstede on Saparua and Fort Beverwijk on Nusalaut; we walked Fort Amsterdam near Hila on Ambon; and in the north we saw Fort Oranje and Fort Tolukko on Ternate, with Spanish-era works on Tidore we climbed up the Portuguese Fort São João Baptista (later taken over by the Spaniards). The island was later integrated into Dutch administration from Ternate, they didn’t need a military presence and the fort was never used by the Dutch.. These posts were not only to fend off other Europeans. They anchored the monopoly: policing deliveries, preventing unlicensed trade, collecting dues and projecting coercion inland.

It puzzled us at first to see substantial forts on compact islands such as Saparua and Nusalaut. Their siting answers the question. From Duurstede and Beverwijk you control narrow passages and can watch the flow of small boats between Seram, Ambon and the Lease Islands. In the seventeenth century those views were the checkpoints of monopoly, where cargo could be seen, quotas enforced and unlicensed trade deterred.

How the monopoly worked (and what we saw).

We expected plantations; we found cloves, nutmeg and other spice and fruit trees scattered through small household gardens. That is how it has always been. Families tend a few dozen trees among sago and fruit. The VOC did not replace this mosaic; it captured it. Villages delivered fixed quotas at controlled prices; free sale was forbidden; when supply threatened margins, the VOC ordered clove trees cut down. On Banda, resistance to nutmeg control produced catastrophe: mass killing, deportation and forced repopulation with enslaved and contract labour. Elsewhere the system was less apocalyptic but still harsh: relocations, punishments and repeated hongi raids kept the market caged. The profits flowed outward; cloves bought cheaply in the Moluccas yielded fortunes in Amsterdam.

For context: hongi expeditions were VOC-sanctioned patrols—often conducted with allied warriors in kora-kora war canoes—that moved from village to village to enforce the monopoly, uproot illegal clove trees, punish smugglers and compel deliveries.

Local memory of control persists. In Hila we heard how the Dutch closed village wells so people were forced to collect water at Fort Amsterdam. The story survives not as grievance seeking redress, but as part of a past that remains near the surface. Research indicates that such actions took place during uprisings or as a temporary punishment.

From VOC to colonial state.

When the VOC collapsed in 1799, its sovereign rights passed to the Dutch state. Unlike Java, the Moluccas saw little new colonial infrastructure. Ambon functioned as a garrison and administrative centre; smaller islands retained their rural character. The military posts were later held by the Koninklijk Nederlandsch-Indisch Leger (KNIL), the Royal Netherlands East Indies Army, while civil administration was thin. Protestant missions expanded in the nineteenth century, especially on Ambon, Saparua and Nusalaut, building schools and training teachers and pastors; this helps explain the islands’ long-standing literacy and the density of church life we still observed.

The uprising of 1817: Pattimura and Martha Christina.

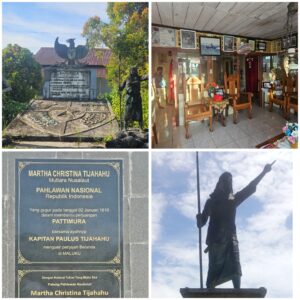

Resentment surfaced quickly. In 1817, after a brief British interregnum during the Napoleonic wars, the region returned to Dutch rule and a widespread revolt broke out. On Saparua, Thomas Matulessy—Kapitan Pattimura—led villagers to seize Fort Duurstede and expel Dutch authority for several months. The movement spread to neighbouring islands. On Nusalaut, Martha Christina Tiahahu, only seventeen, joined the rebellion; captured and exiled by sea, she refused food and died in transit. The Dutch crushed the revolt; Pattimura was executed in Ambon on 16 December 1817 and, with companions, publicly displayed as a warning. In memory the meaning reversed: both are now honoured as national figures; Tiahahu is remembered as a national heroine. The University in Ambon and its airport are among the different place that bear Pattimura’s name.

Loyalty, The KNIL And Exile To The Netherlands

Paradoxically, the Moluccas later became a key recruitment ground for the KNIL. Military service offered steady income and status in a region with few alternatives; the Dutch regarded Christian Moluccans as reliable soldiers. The association lasted into the mid-twentieth century. After independence in 1949, fearing retribution, about 12,500 KNIL soldiers and their families who choose not to become Indonesians, were transported to the Netherlands with the promise of the Dutch Government of a temporary resettlement and eventual return to an independent Moluccas. It became permanent. Today their descendants in the third and fourth generations maintain strong ties. During our visit we encountered many Dutch-speaking Moluccans, particularly in Ambon, visiting family and navigating layered identities—in our discussions with some of them it became clear that even the 3rd and 4th generations often feels neither fully Dutch nor fully Moluccan, but both.

War and memory: Galala, Laha and Brisbane

The Second World War left deep scars. At Galala War Cemetery in Ambon we visited the graves of Australian soldiers from Gull Force, KNIL servicemen, Indian troops and others; the cemetery stands on the site of a former Japanese prison camp. By pure chance I came upon the grave of a person about whom I had written for the Dutch Australian Cultural Centre. From a lookout toward Laha, near today’s airport, the bay lies calm, though it was the site of one of the war’s most notorious massacres in the archipelago, taking Australian and KNIL lives. In Ternate’s Sultan’s Palace we saw photographs of the royal family evacuated in 1945 by Z Special Unit to Australia, with time at Camp Columbia in Brisbane—a small but telling link between the Moluccas and Australia.

Present life, services and visible contrasts.

Village life remains based on smallholder farming, with roadside stalls for extra income. Larger village shops are often run by Chinese-Indonesian families, reflecting long trading traditions. Government provides roads, electricity and water, but services are limited; education and healthcare are subsidised rather than free, and roads suffer from potholes and heavy tropical downpours. The contrast between clean household compounds and plastic litter in public spaces is striking. Police and military facilities stand out in quality—well-resourced posts and housing—echoing the strong military influence in the country’s politics. More broadly, political tensions in Indonesia have not vanished; on Java, recent student protests against corruption and police brutality have again turned deadly. In the Moluccas, the communal conflict of 1999–2002 between Christian and Muslim communities remains part of living memory, though daily life now appears calm; the Peace Monument in Ambon we visited expresses a conscious choice for coexistence. Our (Christan) guide Stevy fled Amban at that time, received refugees status in the Netherlands and stayed there for seven years, after which he moved back to Ambon.

While daily life is largely peaceful, there are still underlying sensitivities between Christian and Muslim communities, shaped by the history of the conflict in 1999–2002. One visible expression of religious identity is the prominent presence of both churches and mosques. The call to prayer begins very early, often around 4 a.m., and is broadcast at high volume from multiple mosques, something that residents themselves sometimes mention as a point of everyday inconvenience. Yet people are careful in how they speak about it, aware that any criticism may be interpreted politically as anti-Islam, and therefore most prefer to maintain harmony by avoiding direct confrontation on these matters.

Identity, language and anecdotes

On Saparua, Dutch flags and references to the Netherlands decorate walls and billboards; support for Dutch football is enthusiastic. In Ambon we stayed at Natsepa Beach, where local lore holds that the name preserves a colonial-era farewell—naar zee, pa, a child’s plea for one last trip to the shore. It is not established etymology, but it captures well how language and memory mingle along the coast.

Conclusion

Our visit to the Moluccas was not simply a journey into history; it was an encounter with living memory. The past is not sealed away. It endures in forts and churches, in graves and village stories, in family migrations that span oceans, and in the ordinary gestures of hospitality that greeted us everywhere. The world once came to these islands for something as small as a clove bud. Its legacies still shape identity, memory and belonging across these islands of spice. Spices are still an important part of the Moluccas economy, sold internationally but now farmed by independent and free local farmers.

Tracing Dutch Batavia: From the Old City to Buitenzorg

Exploring Java’s Colonial Legacy: Bandung, Cimahi, Yogyakarta and Surabaya

Kapitan Pattimura (Thomas Matulessy) and the 1817 Maluku Uprising

The Long Road to Independence: From Colonial Resistance to the Birth of Indonesia