See also:

Depending on the changes in climate Aboriginal people have lived in and around the Brisbane area for over 35,000. During the last ice Age it was dry grass land. With the sea 30 kilometres further east. So many of the early settlements will now be under water. The first archaeological sites date from around 22.000 years ago and are on the sandhills of Stradbroke Island. With the retreating ice sea levels started to rise and the area became a shallow bay with large swamps, with hundreds of creeks and little waterways. While it had become dryer with again more woodlands when the British military arrived, it still was a rather wet area. Rising seawater had forced the Aboriginal people to move west. It wasn’t till 6.000 years ago that the current coastline was established.

At that time the people here lived in a subtropical paradise along the sea, the rivers and the many creeks. There was a large variety of food and depending on the season they had many feats when certain fruits or animals were plentiful. It has been estimated that the people needed to spend 2 hours a day to get their food for a 24 hour period. It was most likely the most densely populated Aboriginal area at the time the Europeans arrived. The people lived in extended family groups and were all part of the language group of the Turrbal people. Their area extended to the Gold Coast, Moggill, Logan and included the islands in the Bay. The Turrbal in turn were part of the larger Yugarra (Jagura) language group whose area extended from Moreton Bay to the base of the Toowoomba ranges. The Australian word ‘yakka’ (as in ‘hard yakka’) came from the Yugarra language (yaga, ‘strenuous work’). While they were nomad people they travelled in a relative smaller area and had more semi permanent settlements. The people further inland were more mobile and travelled over larger areas.

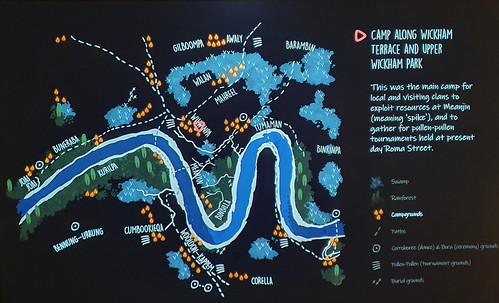

At one of the entrances at Roma Street Parkland we find several Aboriginal words: Mianjin , Umpi Korumba , Maiwar, Mahrel , Turrbal and Barrambin. We will come across these names in the text of this chapter.

Within the Turrbal group there were dozens of groups (clans) with each one of them living within distinct separate areas. Some of the names of these smaller groups are known to us. The Ngundari aboriginal tribe/family group lived around the part of the river were Henry Miller established the penal settlement. They were removed from the north side of the river but continued to inhabit in what we now call South Brisbane.

The traditional name for the area that became the penal settlement was ‘Mianjin /Meean-jin’ (Yuggera/Turrbal languague) which refers to the spike of land which formed Petrie’s Bight.

We have one of the most amazing insights in the people that lived in the Brisbane area thanks to Tom Petrie, a son of Andrew Petrie who arrived in 1837 in the penal colony as the supervisor of the works department. As a 3-month-old baby Tom arrived in Sydney in 1831, he was 5 when he arrived in Brisbane. He rapidly made friends with local Aboriginal people, he learned their language and throughout his life he did spend lots of time with the Aboriginal people, participating in hunting and the various ceremonies. I have seldom red such informed document about local Aboriginal history, which was written down by his daughter in 1904 in the decade before Tom died. The book is called Tom Petrie’s Reminiscences.

It is estimated that at the time the British arrived some ten thousand people lived along the river, which the Turrbal called Maiwar.

As elsewhere in Australia the people were hunter gathers in the way that they had no fixed places they stayed for long. They moved along within their extended territories. This was well planned and they went to specific areas depending on the seasons and on what food supplies would be available where. They also managed their environment using the fire stick, protecting certain trees and plants and they also used various fishing techniques. They interacted intensively with the neighbouring groups within the larger Turrbal area and often collaborated in together managing their environment. Tom Petrie witnessed how the Turrbal people used turtles to catch sea mullet at Moreton Island.

The Turrbal people met for thousands of years in the area what is Roma Street precinct – but than all the way to the river – and extended into what is now Victoria Park (Barrambbin – windy place). The creek and its ponds extended all the way to where now Town Hall is situated. These sites were popular for camping, pullen pullen (fighting) and corroboree, not just for the local tribes but also a place where many tribes from further away gathered. They also hunted for ducks, harvested waterlilies and used the tide to trap fish, where the creek entered the river (Riverside Quarter).

The creek and ponds area fell within the convict settlement and these grounds were rapidly taking over by the British military. And the extended area (Victoria Park and beyond) that was still available to them during that time, was taken away once the free settlers arrived from the 1850s onward.

Kippa and Bora Grounds, Pullen Pullen and Corrobborees

Tom describes the initiation ceremonies that took place for the young boys. Tribes from all over the area came together for the ceremony and the larger ones could take place over several months. In general these initiations took place as fixed sites. It looks like that they were called Kippa grounds (they are very similar to the Bora grounds in the Sydney area that I describe in the history of the Darkinjung). One of the Bora grounds was at Humpybong on the Redcliffe peninsula and a suburb here is called Kippa-Ring.

Kippa is the name for a boy that is going to be initiated. The central part of the site were two rings, approx. 200 meters apart, linked with a strait path in between them. The big ring was approx. 20 meters in diameter and the small one, 5 meters in diameter. Most of the circles were created by stones. The Bora Ground could also contain geometric symbols build in the sand as well as images representing their deities. There could also bee carvings in the trees and in certain rock surfaces.

While some of the details that I describe in the Darkinjung ceremonies do differ, the similarities are far greater. According to Tom, the Brisbane tribes went to the Kippa ground at Samford, some 20 kms inland. After the Kippa ceremonies were finished the various tribes moved back to their traditional lands. However, on the way neighbouring tribes stayed together and went to the pullen pullen. The possibly meaning of the words pullen pullen are “to die” (or “not to die”) or “fighting” (or “fighting ground”).

I spend two weeks with the Pitjantjatjara people in Angatja in the Central Dessert in 1989. We were with a groups of 15 white people and were taken on a journey of Aboriginal life in all of its aspects at the end of this learning process we went through an initiation ceremony – of course no comparison to the real ceremony. We were given new names, had to perform certain dances and were body painted in their traditional way.

The Brisbane and their neighbouring tribes went the pullen pullen grounds at the above-mentioned area what is now Roma Street Parkland (they are marked on the map above). Here the tribes faced each other for fights. This was partly a conquest of strength and partly to settle disputes. Tom observed fierce fighting with spears and stone axes with caused serious wounds but there were no killings. Fights were organised for periods of 30 to 60 minutes over several days. After each fight, each group went back to its own camp and in between they all went out for hunting, fishing, etc. After they were all satisfied, the fights ended and everybody this time went back to their own tribal areas. Pullen pullen were recorded by several sources throughout the 1840s and 1850s.

There is an 1850 article in the Moreton Bay Courant:

Native Amusement -The aborigines held a grand “Pullen-Pullen” last week, near Brisbane. Many of the “Ningy-Ningy” and Limestone blacks attended. We are informed that some of them received spear wounds upon the occasion, but no deaths occurred.

The Ningy Ningy people lived in Moreton Bay and the Limestone Blacks were people from what is now Ipswich. The area and this pullen pullen could have been taken place in Redcliffe.

Tom Petrie also records such a large gathering around 1850 in the Roma Street Parkland/Victoria Park area. I have abstracted Tom’s story here: The last big fight at the pullen pullen (Roma Street Parkland)

Corroborees were events that could be very informal for example when a guest arrived from a neighbouring tribe. There were also much larger events which were planned well in advanced or at certain fixed times in the season. When I spend two weeks with the Pitjantjatjara people in the Central Dessert in 1989 we had such informal corroborees (Inma in their language) every night where we son, danced, told stories and so on.

Tom Petrie was a small boy when he observed one of the much larger gathering:

Once there was a great gathering from all parts of the country, the different tribes rolling up to witness a grand new corrobboree that the Ipswich tribe had brought… Altogether there were some seven hundred blacks, and they were camped in this wise: The Brisbane, Stradbroke Island, and all from the Logan up to Brisbane had their camp at Green Hills (overlooking Roma Street Station…), the Ipswich, Rosewood and Wivenhoe tribes were on Petrie Terrace, where the barracks are and the Northern tribes camped on a site of the present Normanby Hotel.

Massacres

While there were the occasional clashes with the local Aboriginal people, in general the convict and early settlement era was rather peaceful as the colony was limited to the penal settlement. In Brisbane itself it was not until the mid to late 50s and in particular the 1860s and 1870s when we can talk about war.

In the 1840s and early 1850 Aboriginal people participated in the local activities. They won prices in the regattas , running competitions and they were cheered on by large crowds both whites and blacks. At that point in time there was not yet a distinct sense of patriotism. People were still very much creating a new life for themselves perhaps with more of a legion to where they came from than from where they were settling. In that respect the Aboriginals were just another group in their society, rather than a outside group. Unfortunately this rather peaceful period didn’t last all that long already in 1852 the Aboriginal people were mentioned as being troublesome. Those who started to adapt appeared in strange outfits, partly dressed in discarded clothes from white people, partly naked and increasingly the white people started to take issue with that.

Already in the 1840s when the squatters started to arrive during we can start talking about a war in the Darling Downes and Upper Brisbane regions.. The Aboriginal people were time and time again pushed away from their land and they obviously resisted this but they didn’t have any chance against the guns of the settlers and the Native Police.

One of the most famous resistance fighters was Dundalli a tall and fierce man from the Dalla people north of Brisbane. He was able to escape capture for more than a decade, he was accused of killing a shepherd at the Archer’s property Durundur as well as murder of the squatter Andrew Gregor. Dundalli also lead a range of other attacks on the Whites and several of his warriors were killed. He was finally captured in 1854 and hanged in front of the prison in Queen Street the following year. This was the last official public hanging in Queensland. In 2023 it was officially decided to commemorate this event every year on 5 January.

While the Aboriginal people were officially subjects of the Crown, they had no rights and the British Law was always used against them. While some 1500 settlers were killed in this war, the Aboriginal casualties among the approximate 200 Queensland tribes are estimated to be around 65.000.

The above mentioned Ningy Ningy were also the people that were subject to the first of many massacres of Aboriginal people in Queensland. Sadly, many of these massacres were undertaking by the Native Police under the command of British officers, most of the native policemen were recruited in NSW. They often went on their expeditions with the aim to kill. There is also the case of the execution of two Aboriginal men, who were hanged from the windmill. Now close to 200 year later we still need the Black Lives Matter campaign to address these and many other unforgivable murders.

Witnessing to Silence (2004) remembers all known massacres of Indigenous people within Queensland, listing 94 such sites. The corpses on these sites were hidden either by burning or submerging in bodies of water. Aboriginal Artist Fiona Foley engaged in some deception to ensure the work’s installation, telling its commissioners (Brisbane Magistrate’s Court) that the work was about sites of natural phenomena – fire and flood.

There are also records that the Native Police poisoned waterholes and flour and that the hunted Aboriginal people protecting their lands and killed them in cold blood. A very large proportion of the Aboriginal people however were killed by small pox. As I have discussed in the history of the Darkinjung people in NSW, there has been a longstanding suspicion that small pox was deliberately released among Aboriginal people. And looking at those tactics, biological warfare would fit into such scenarios.

I totally agree with the Aboriginal people that Australia as a country and in particular Queensland as a state still has a lot of truth telling to do. We will never be able to fully reconcile unless that has happened. On the positive side progress is being made.

Barrambin

The longest surviving Aboriginal cultural heritage site in the Brisbane CBD area is Barrambin (windy place), in convict times known as York’s Hollow. It includes the area now covered by Victoria Park, the Brisbane General Hospital, and the National Agricultural and the Exhibition Grounds.

Prior to 1890, Breakfast Creek flowed through York’s Hollow and a chain of ponds provided for fresh water (hence the name hollow). The name York’s Hollow refers to the name of an Aboriginal elder known by whites as the Duke of York. This man was an acknowledged leader of the local Turrbal people. Aboriginal spokeswoman Maroochy Barambah who claims to be a direct descendant of the Duke of York indicated that the name was an anglicised version of his Indigenous name Daki Yakka.

Brisbane’s Boundary Streets

In the early years of the free settlement (1842-1865) the Aboriginal economic and ritual activities were still tolerated around Brisbane Town. Tom Petrie often went hunting and collecting honey with the Aborigines along Bowen Terrace, Teneriffe, Bowen Hills, Spring Hill and Red Hill.

Of course, as elsewhere in the country soon after the arrival of the British soldiers and their prisoners, Aboriginal life – as these people had known it for millennia – came to a crashing end. There were the many foreign illnesses that killed large numbers of the population. It is estimated that the mortality rate was as high as 80%. As the convict settlement became established the Aboriginals living here were – as mentioned above – removed from the North side but continued to inhabit the South Brisbane area.

Until the 1850 they could freely move through the area including the settlement. However, this started to change. While they remained tolerated within the settlement during the day, they were excluded at sunset. In the beginning there was hardly any policing, so the curfew did not have a great effect. However, by the 1870s mounted troopers used to ride out about 4 pm cracking stock whips as a signal for the Aborigines to leave town. The curfew was not specially aimed at the Aboriginal people, they also kept out, thieves, prostitutes, and homeless people. However, the main people effected by the curfew were the Aboriginals.

The numerous ‘Boundary Streets’ around Brisbane represent many of the old boundaries of Aboriginal exclusion. In 1852, ironbark posts were placed at intervals along the boundaries of the one square mile of the Brisbane Town settlement.

In relation to the Boundary street in Spring Hill there is a further story to tell. In 1849, British migrants sponsored by the Reverend Dunmore Lang arrived on the ship Fortitude. The abrasive personality of the clergyman and his high-handed approach were not well received by the authorities. They refused cooperation and Dunmore claimed that British Government promises for land grants for his 1000 immigrants were not honoured. The migrants had to find accommodation for themselves. Some rented rooms in Spring Hill.

The Boundary street here became the delineated with the area of Barrimbin. Fences were made by the newcomers that were erected every night to keep the Aboriginal people out of Spring Hill.

Tom was saddened about the decline of the Aboriginal people. Where he could he provided protection, argued their cause before the authorities and in 1877 was instrumental in establishing a reserve for them on Bribie Island. They also received a boat, fishing gear and other necessaries. The fish they caught and the Dungong oil they produced was sold in Brisbane for which they could buy food for their community. Sadly the incoming government under Premier Thomas McIlwraith rudely abandoned the reserve without providing any other alternatives for the rapidly dwindling Aboriginal community. His pastoral background might have been of influence in his indifference for the Aboriginal community. When Tom asked what the old folks of the community should do he answered: “Oh, let them go and work like anyone else.” Tom received support from the churches but all at no avail. Many of the abandoned died of alcohol abuse.

It estimated at the time settlers arrived the Aboriginal population was around 250.000 people, by the 1920s this number had dropped to around 20.000.

Bunya Pines

A sacred tree for the Turrbul was the Bunya Pine. These trees grows to a height of 30–45 metres, and the cones, which contain the edible kernels, are the size of footballs, they are sweet before being perfectly ripe, and after that resemble roasted chestnuts in taste. They are plentiful once in three years, and when the ripening season arrives, which is generally in the month of January. When that happened the Aboriginals gathered from far and had enormous feast that lasted for weeks. Interestingly Andrew Petrie was the first European that described the tree. He was told by his Aboriginals friends that this tree was sacred and he prevented the settlers to cut these trees down. He was able to persuade the government to protect the area and stop the new settlers from cutting them down. However, with an eye on profits, this was over ruled a few years later. In 1830 there were 26 sawyers active in the district. In 1835 the commandant reported that most of the useable trees in a radius of 20 miles had already been cut. Nevertheless the government in Sydney demanded more timber. In 1852 Scottish-born Australian Presbyterian minister, writer, historian, politician and activist John Dunmore Lang complained about the wilful destruction of of trees, many of which were rare species. Many were unnecessarily cut down got drifted away in the raft transports. Many of the islands in the bay were totally denuded of their native trees. Mt Cooth-Tha was previously called One Tree Hill, a good indication what happened with the tress here.

Turrbal or Jagara place names in Brisbane.

Many suburbs and places in Brisbane have names derived from Turrbal words:

- Woolloongabba is derived from either woolloon-capemm meaning “whirling water”, or from woolloon-gabba meaning “fight talk place”.

- Toowong is derived from tuwong, the phonetic name for the Pacific koel.

- Bulimba means “place of the magpie-lark”.

- Indooroopilly is derived from either nyindurupilli meaning “gully of leeches”, or from yindurupilly meaning “gully of running water”.

- Enoggera is a corruption of the words yauar-ngari meaning “song and dance”.

- South Brisbane together with West End and Highgate Hill is known as Kurilpa (meaning water rat).

- Moggill – Moggil -water dragon

- Mt Coo-tha – Ku-ta – dark native honey

- Maroochy (Marootchy Doro)= Muru-kutchi, meaning red-bill and referring to the black swan, which is commonly seen in the area.

- Caboolture – Kabul-tur – place of carpet snakes.

The situation for the Aboriginal people became more and more difficult with the floods of immigrants arriving in the colony taking over more and more land in total disregard of their rights to the land.

As a sign of the time, the tympanum of the Town Hall is titled: “The progress of civilisation in the State of Queensland”. The two Aboriginals to the left of the tympanum are described in the programme of the opening of the building in 1930 as : “The native life is represented dying out before the approach of white man.” The fact that this did not happen is a tribute to the Aboriginal people.

Despite all these discriminatory and criminal actions against the Aboriginal people there is still a vibrant community in Brisbane, with of over 15,000 First Nation People. Clearly showing the resilience of our First People.

Convict History of Brisbane TOC

On separate occasions I have also written about the Darkinjung people who lived between Sydney and the Hunter Valley. I wrote that as part of the history of Bucketty where we lived from 1986 till 2019. In 1989 I spend to weeks with the Pitjantjatara People in the Central Dessert and I a wrote down my experiences on this fascinating journey.